My thoughts on the Naval Ravikant meditation challenge

Are you able to do nothing? Are you conditioned to check your phone if there is a second of boredom? Are you able to go for a walk without throwing on a podcast or listening to music? What is the first thing you do when you wake up? Do you feel satisfied at the end of your day? Do you spend your time on important things or on urgent matters? When is the last time you took five minutes to do nothing?

All of humanity’s problems stem from one’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.

Blaise Pascal

The Experiment

I completed Naval Ravikant’s meditation challenge during February and March of 2021.

He describes the challenge briefly in the tweetstorm below and during appearances on various podcasts. Here are a few tweets from the thread that explain the technique:

- Prepare for meditation by sitting quietly in the morning, with eyes closed and back upright, in any comfortable position that will minimize movement.

- Make no effort for or against anything. Whatever happens, happens. Surrender to yourself in the moment. Resist nothing and reject nothing, including the urge to resist and reject.

- No focus, no mantra, no dharma, no chakras, no Buddhas, no gurus, no gratitude, no scripture, no temple, no music, no gadgets, no apps are required. Some may be helpful, but eventually all will have to be left behind. Start simply, because that’s where this all ends.

- There are many meditation methods, but “no effort” is the universal method. Every creature at all times can choose to do nothing.

- There’s no need to get up to record a thought. If the idea was good, it’ll come back. If it doesn’t come back, it wasn’t that good.

- The point of meditation is not to become “a meditator” – in reality, there’s no such thing. If it doesn’t bring lasting and effortless change, drop it, before it becomes another struggle and another chase.

My Experience

I took some notes during the two months of practice in an attempt to reduce bias.

The first 10 days of the Naval 60×60 have been alright. It was easier to do it first thing in the morning in a quiet room. Just get out of bed if you are somewhat awake. The meditation is not much different from snoozing the hour before getting up.

My brain ran wildly for most of the hour on most days. Sometimes, I would go on 20-minute spurts of creative flow. I tried to write down my thoughts on the whiteboard once the session was done. My thought rate tended to slow down a bit by the end of the session and the end of the 60 days. I thought peace or bliss would emerge once the muddy water cleared. Instead, a neutral feeling and boredom emerged when things settled.

I found weekends made it harder to meditate immediately after waking up. We have a cultural myth that Saturdays and Sundays are special. We also tend to be more social on weekends which tends to disrupt our sleep schedule. Get some good sleep or else you’ll just spend 60 minutes suffering.

I started having doubts about the technique on day 15. Those doubts dissipated around day 20. I took a note on day 36 that I was skeptical of the effectiveness of the technique. The promised land was to reach psychological “Inbox Zero”. My brain was still running circles for most if not the entirety of the sessions. The few minutes of quiet were not quite the promised positive feelings. Maybe I needed to stick with the practice longer.

Days 37-39 have been easier. This made me realize the natural ebb and flows we go through. Most of the time the best thing to do is just sit tight and wait till your mud settles. Impermanence is everywhere. Trying to cling to pleasant sensations and avoid unpleasant ones is a pointless and exhausting game.

I broke my dominant hand on day 44 of the challenge. The discomfort made it unpleasant to sit still for an hour.

Nothing epic happened in the last stretch.

Looking Back on the Numbers

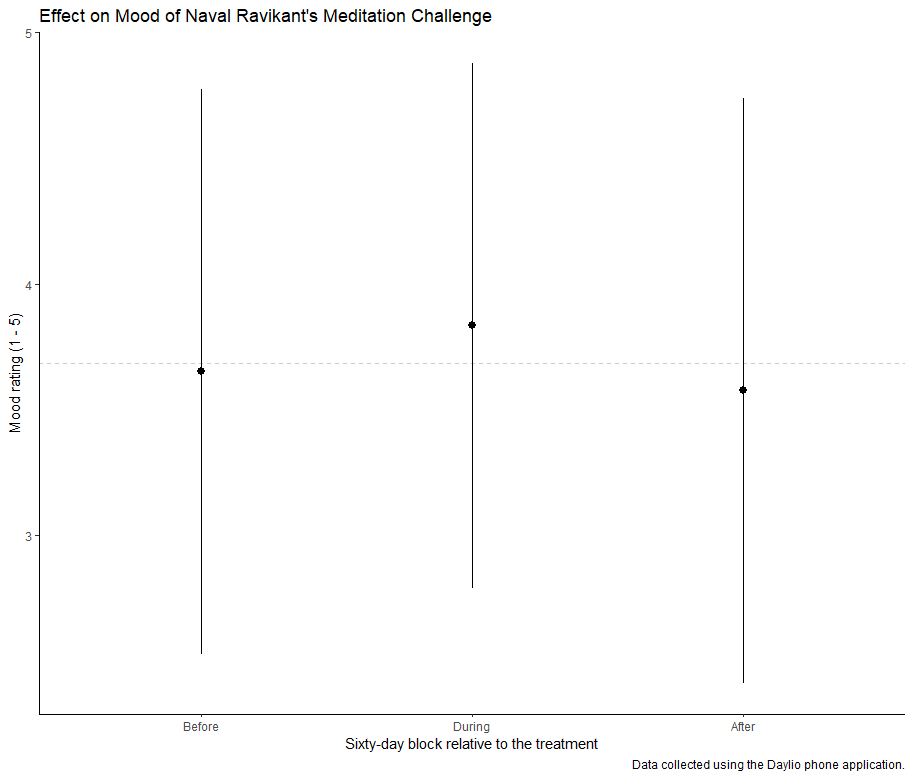

I have been tracking my mood for over 1000 days as of this writing. I use the Daylio app to rate my days on a scale ranging from one to five (five being the happiest). Since the challenge was 60 days, I thought I could look at my mood for the 60 days before, the 60 days during, and the 60 days after the challenge for a total sample of 180 days.

As you can see in the picture above, my average mood seems to have increased slightly during the 60 days I was meditating compared to the 60 days before and after. The dashed horizontal line is the average mood from the entire sample. The error bars indicate one standard deviation away from the mean. We can take a look at the exact numbers below.

| Period | Average Mood (1 – 5) | Standard Deviation of Mood |

| Before | 3.65 | 1.12 |

| During | 3.83 | 1.04 |

| After | 3.58 | 1.16 |

The results are consistent with my previous findings that my average mood over 1000 days was about ![]() out of five. Is this average meditation mood rating of 3.83 really that much better than 3.65 (before) or 3.58 (after)?

out of five. Is this average meditation mood rating of 3.83 really that much better than 3.65 (before) or 3.58 (after)?

We can use statistics to check whether the differences between the three group means are statistically different. We get the following results when using John Tukey’s test of honestly significant differences (HSD).

| Period | Difference | Lower Bound of 95% CI | Upper Bound of 95% CI | p-value |

| During – Before | 0.18 | -0.29 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

| After – Before | -0.08 | -0.54 | 0.39 | 0.92 |

| After – During | -0.26 | -0.73 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

Note that since none of the p-values are less than ![]() , we can’t conclude that average moods are statistically different. In other words, the effect of the Naval meditation challenge did not significantly affect my mood. Going from the baseline average mood of 3.65 from the 60 days prior to the experiment to 3.83 only represents a 5% improvement in mood (

, we can’t conclude that average moods are statistically different. In other words, the effect of the Naval meditation challenge did not significantly affect my mood. Going from the baseline average mood of 3.65 from the 60 days prior to the experiment to 3.83 only represents a 5% improvement in mood (![]() ). This increase aligned with my subjective experience of feeling five to ten percent happier overall despite the effort needed to sit still for an hour every morning. It also lines up with Dan Harris’s book,10% Happier.

). This increase aligned with my subjective experience of feeling five to ten percent happier overall despite the effort needed to sit still for an hour every morning. It also lines up with Dan Harris’s book,10% Happier.

Maybe this five to ten percent improvement in mood has a practical significance although it was not statistically significant. I could repeat this experiment every year to verify whether this slight improvement could be replicated for myself consistently. However, I think it is safe to assume that individuals will vary quite a bit. Extrapolating from one’s experience to everyone else is almost surely foolish. It is important to note that my average mood was lower than baseline for the 60 days after the challenge. Further research needs to be done to investigate the lasting effects of the Naval challenge.

We can also look at whether my mood was more stable during the challenge compared to before and after. The lower standard deviation of 1.04 compared to 1.12 (before) and 1.16 (after) is an indication that my mood varied slightly less during the challenge. Again, this difference was not statistically different according to Bartlett’s test of homogeneity of variances. It is worth reiterating that small differences in mood can lead to large differences in outcomes and subjective quality of life.

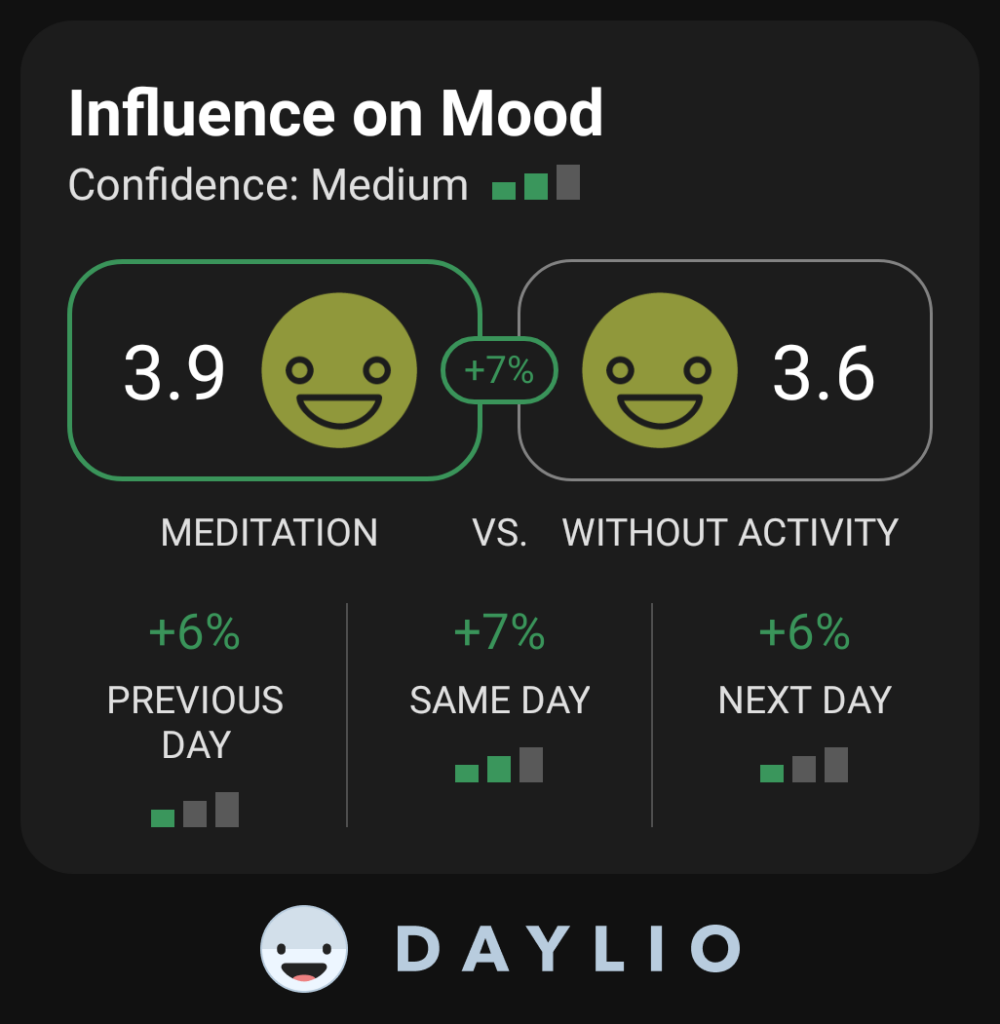

Note that the Daylio statistics below include a few days out of the sample but they are essentially looking at the same time period from the earlier analysis. They report a 7% improvement with a “medium” confidence level. From experience, Daylio is quite liberal in their conclusions. I am not sure what a medium confidence level entails. All I know is that I am not ready to conclude that meditation had a significant impact on my mood and on my life.

All the code and data used for this article can be found here.

Closing Thoughts

I can only comment on my own experience. I did not reach “Inbox Zero”. There were obviously some benefits to the practice. I felt more intentional about my days. I realized how much stuff runs in the background of my brain. Writing things down on paper was a great way to clear that source of mental traffic. I felt slightly more mindful throughout the day. I felt like I could see the bigger picture more clearly than before.

An unexpected realization was that to connect the “pay yourself first principle” from The Wealthy Barber applies to how we spend our time. I would benefit from “investing” 10% of my waking hours in myself. If we take the principle literally and assume 16 hours per day, we get that 10% of 16 hours is .![]() . In an ideal world, I would have built the habit (automated) of investing in myself the first hour and a half of my day. Working from home has made this habit easier to adopt. The goal is for this habit to be robust enough to withstand commuting to work and raising children.

. In an ideal world, I would have built the habit (automated) of investing in myself the first hour and a half of my day. Working from home has made this habit easier to adopt. The goal is for this habit to be robust enough to withstand commuting to work and raising children.

The practice did not have obvious downsides. The main drawback that I can think of comes from the opportunity cost associated with the practice. I tend to work best in the morning. Every hour spent meditating is one hour less spent doing something else. I try to do the tasks that need the most focus first thing in the morning. At times, it was difficult to not feel like sitting on a milk crate for 60 minutes during the most productive time of my day was not a waste of time.

I also experienced clear diminishing returns. It felt like I got most of the benefits of the challenge in the first 15 days or so. Maybe a shorter challenge would have resulted in the same benefits. It begs the question. Can we get 10% happier with less time than 60 minutes for 60 days? This concept is often referred to in the medical space as the minimal effective dose (MED). Maybe the full dose (60 days of 60 minutes) is required/beneficial for first-time meditators. I can imagine that this type of meditation would be extra useful and challenging for hyper-busy people who never slow down.

I am happy I stuck with the practice and completed the challenge. There is definitely something to be said about the value of discipline and having a steady practice (whatever it may be). That said, meditating an hour every morning was unpleasant. I am naturally attracted to other reflective practices such as long walks and writing. It might make more sense to adopt a practice that feels right and gives me roughly the same benefits. It reminds me of the saying that the best workout is the one you’ll actually do.

Tip & tricks

- Schedule the do not disturb option so it is on in the morning.

- Empty your mind before and after on paper. I used my white board.

- It may help to blindfold yourself if you have a hard time keeping your eyes closed.

- I used the Waking Up app timer with a bell at 30 minutes and 60 minutes.

- Using a habit tracker and a support group are good ways to keep you on track.

Do you have the patience to wait till your mud settles and the water is clear?

Lao Tzu

Takeaways

- Some ideas need calm water to float to the surface.

- Opportunity cost applies to habits. I might be better off doing something I enjoy more.

- Focus on the big rocks. It does not make sense to sacrifice sleep to squeeze in the latest “biohack” in your day.

- Things can have practical significance although they are not statistically significant.

- Pay yourself first with the first hour of the day.

Articles you might like if you’ve enjoyed reading this one

- What I Learned from Tracking my Mood for 1000 days

- Make Contracts Work for You

- New Year’s Resolution ➡️ New Month’s Resolutions

- No Phone in the Morning Experiment

- The Wealthy Barber- Book Notes

- Atomic Habits – Book Notes

- All the code and data used for this article can be found here.

Affiliate Links

- 10% Happier – Dan Harris

- The Wealthy Barber – David Chilton

- Atomic Habits – By James Clear