Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver BurkemanMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

A bit repetitive at times. The main ideas are an antidote to our current productivity-driven culture. The gist of it is that accepting our finiteness is healthier than pretending that we are infinite beings.

View all my reviews

Main Takeaways

- “Happiness is only real when shared.” – Christopher McCandless (Into the Wild)

- Having absolute control over our time and schedule is the wrong goal. This will only lead to loneliness. Digital nomads tend to be lonely.

- “You can make the kinds of commitments that remove flexibility from your schedule in exchange for the rewards of community, by joining amateur choirs or sports teams, campaign groups or religious organizations. You can prioritize activities in the physical world over those in the digital one, where even collaborative activity ends up feeling curiously isolating. And if, like me, you possess the productivity geek’s natural inclination toward control-freakery when it comes to your time, you can experiment with what it feels like to not try to exert an iron grip on your timetable: to sometimes let the rhythms of family life and friendships and collective action take precedence over your perfect morning routine or your system for scheduling your week. You can grasp the truth that power over your time isn’t something best hoarded entirely for yourself: that your time can be too much your own.”

- Reframe your view of time.

- “Each hour or week or year is like a container being carried on the belt, which we must fill as it passes, if we’re to feel that we’re making good use of our time. When there are too many activities to fit comfortably into the containers, we feel unpleasantly busy; when there are too few, we feel bored. If we keep pace with the passing containers, we congratulate ourselves for “staying on top of things” and feel like we’re justifying our existence; if we let too many pass by unfilled, we feel we’ve wasted them. If we use containers labeled “work time” for the purposes of leisure, our employer may grow irritated. (He paid for those containers; they belong to him!)”

- Lawers find it difficult to let go of the conveyor model of time because they have billable hours.

- Aim to orient your view of time around the tasks that need to be done instead of thinking of time as a river that flows by.

- “At any given moment, you’ll be procrastinating on almost everything.”

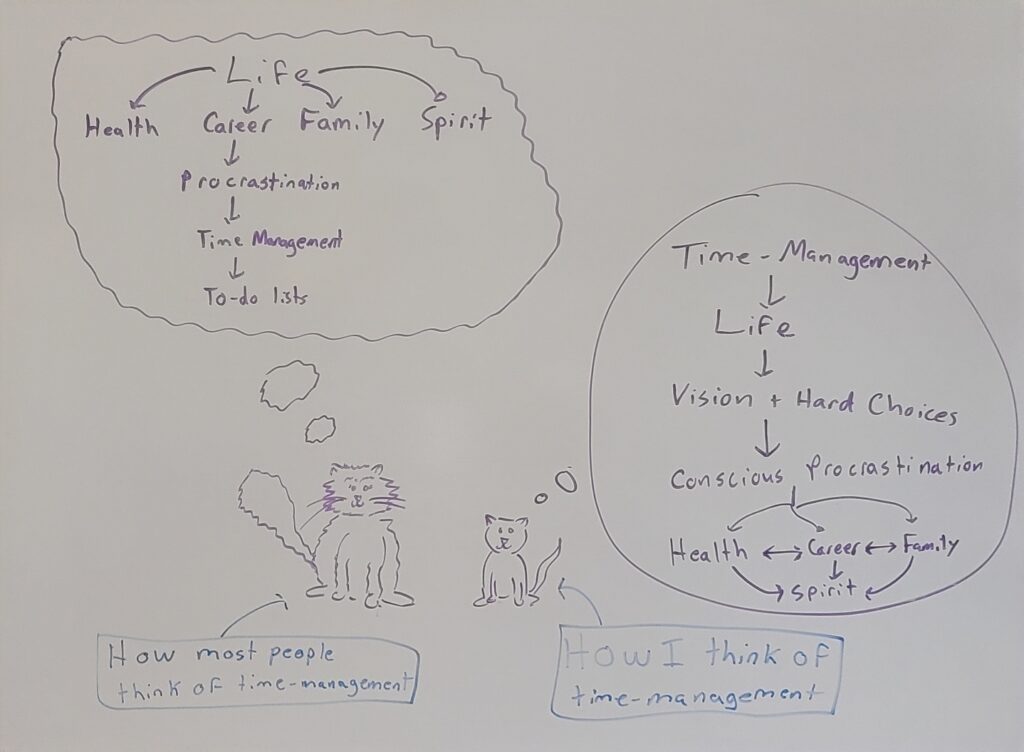

- Become an active procrastinator. Consciously choose what areas of your life you want to procrastinate on. Embrace your finitude and admit that it is impossible to not procrastinate. There are inherent tradeoffs in everything.

- “(The original Latin word for “decide,” decidere, means “to cut off,” as in slicing away alternatives; it’s a close cousin of words like “homicide” and “suicide.”)”

- If we accept the multiverse model of reality, then we kill large branches of our possibility trees with each decision we make. By becoming better at active procrastination, we become better pruners of our trees.

- We live in a world with too many Big Rocks.

- “Buffett’s advice is different: he tells the man to make a list of the top twenty-five things he wants out of life and then to arrange them in order, from the most important to the least. The top five, Buffett says, should be those around which he organizes his time. But contrary to what the pilot might have been expecting to hear, the remaining twenty, Buffett allegedly explains, aren’t the second-tier priorities to which he should turn when he gets the chance. Far from it. In fact, they’re the ones he should actively avoid at all costs—because they’re the ambitions insufficiently important to him to form the core of his life yet seductive enough to distract him from the ones that matter most.”

- “in a world of too many big rocks, it’s the moderately appealing ones—the fairly interesting job opportunity, the semi-enjoyable friendship—on which a finite life can come to grief.”

- “Convenience culture seduces us into imagining that we might find room for everything important by eliminating only life’s tedious tasks. But it’s a lie. You have to choose a few things, sacrifice everything else, and deal with the inevitable sense of loss that results.”

- Embrace hobbies and Leisure

- “To the philosophers of the ancient world, leisure wasn’t the means to some other end; on the contrary, it was the end to which everything else worth doing was a means.”

- “There are positive side effects, like becoming more physically fit, but that’s not generally why people go on hikes. Taking a walk in the countryside, like listening to a favorite song or meeting friends for an evening of conversation, is thus a good example of what the philosopher Kieran Setiya calls an “atelic activity,” meaning that its value isn’t derived from its telos, or ultimate aim. You shouldn’t be aiming to get a walk “done”; nor are you likely to reach a point in life when you’ve accomplished all the walking you were aiming to do. “You can stop doing these things, and you eventually will, but you cannot complete them,” Setiya explains.”

Book Notes

Introduction

Arguably, time management is all life is. Yet the modern discipline known as time management—like its hipper cousin, productivity—is a depressingly narrow-minded affair, focused on how to crank through as many work tasks as possible, or on devising the perfect morning routine, or on cooking all your dinners for the week in one big batch on Sundays.

Oliver Burkeman – Four Thousand Weeks

- “Not only are our four thousand weeks constantly running out, but the fewer of them we have left, the faster we seem to lose them.” Life is like a roll of toilet paper.

- “The problem isn’t exactly that these techniques and products don’t work. It’s that they do work—in the sense that you’ll get more done, race to more meetings, ferry your kids to more after-school activities, generate more profit for your employer—and yet, paradoxically, you only feel busier, more anxious, and somehow emptier as a result.”

- “It’s somehow vastly more aggravating to wait two minutes for the microwave than two hours for the oven—or ten seconds for a slow-loading web page versus three days to receive the same information by mail.” Life is all about expectations and reward prediction error.

- “In 1930, in a speech titled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” the economist John Maynard Keynes made a famous prediction: Within a century, thanks to the growth of wealth and the advance of technology, no one would have to work more than about fifteen hours a week.” What happened? The answer is dopamine.

- “Nobody in the history of humanity has ever achieved “work-life balance,” whatever that might be, and you certainly won’t get there by copying the “six things successful people do before 7:00 a.m.””

It turns out that when people make enough money to meet their needs, they just find new things to need…

OLIVER BURKEMAN – Four Thousand Weeks

Part I – Choosing to Choose

The Limit-Embracing Life

The trouble with attempting to master your time, it turns out, is that time ends up mastering you.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “Each hour or week or year is like a container being carried on the belt, which we must fill as it passes, if we’re to feel that we’re making good use of our time. When there are too many activities to fit comfortably into the containers, we feel unpleasantly busy; when there are too few, we feel bored. If we keep pace with the passing containers, we congratulate ourselves for “staying on top of things” and feel like we’re justifying our existence; if we let too many pass by unfilled, we feel we’ve wasted them. If we use containers labeled “work time” for the purposes of leisure, our employer may grow irritated. (He paid for those containers; they belong to him!)”

- “Historians call this way of living “task orientation,” because the rhythms of life emerge organically from the tasks themselves, rather than from being lined up against an abstract timeline, the approach that has become second nature for us today.”

- ““The clock does not stop, of course,” Eberle writes, “but we do not hear it ticking.””

- And as long as I was always just on the cusp of mastering my time, I could avoid the thought that what life was really demanding from me might involve surrendering the craving for mastery and diving into the unknown instead.”

- “(“We labour at our daily work more ardently and thoughtlessly than is necessary to sustain our life,” wrote Nietzsche, “because to us it is even more necessary not to have leisure to stop and think. Haste is universal because everyone is in flight from himself.”)”

- “Moreover, most of us seek a specifically individualistic kind of mastery over time—our culture’s ideal is that you alone should control your schedule, doing whatever you prefer, whenever you want—because it’s scary to confront the truth that almost everything worth doing, from marriage and parenting to business or politics, depends on cooperating with others, and therefore on exposing yourself to the emotional uncertainties of relationships.”

- “And the more individual sovereignty you achieve over your time, the lonelier you get.”

- “All of this illustrates what might be termed the paradox of limitation, which runs through everything that follows: the more you try to manage your time with the goal of achieving a feeling of total control, and freedom from the inevitable constraints of being human, the more stressful, empty, and frustrating life gets. But the more you confront the facts of finitude instead—and work with them, rather than against them—the more productive, meaningful, and joyful life becomes.”

- “They understood limitlessness to be the sole preserve of the gods; the noblest of human goals wasn’t to become godlike, but to be wholeheartedly human instead. In any case, this is just how reality is, and it can be surprisingly energizing to confront it.”

…as the journalist Anne Helen Petersen writes in a widely shared essay on millennial burnout, you can’t fix such problems “with vacation, or an adult coloring book, or ‘anxiety baking,’ or the Pomodoro Technique, or overnight fucking oats.”

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

The Efficiency Trap

There’s no reason to believe you’ll ever feel “on top of things,” or make time for everything that matters, simply by getting more done.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “Maybe you can’t keep your current job while also seeing enough of your children; maybe making sufficient time in the week for your creative calling means you’ll never have an especially tidy home, or get quite as much exercise as you should, and so on.”

- “The “efficiency trap.” Rendering yourself more efficient—either by implementing various productivity techniques or by driving yourself harder—won’t generally result in the feeling of having “enough time,” because, all else being equal, the demands will increase to offset any benefits. Far from getting things done, you’ll be creating new things to do.”

- “You begin to grasp that when there’s too much to do, and there always will be, the only route to psychological freedom is to let go of the limit-denying fantasy of getting it all done and instead to focus on doing a few things that count.”

- “When people stop believing in an afterlife, everything depends on making the most of this life.”

- “The more efficient you get, the more you become “a limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations,” in the words of the management expert Jim Benson.”

- “It’s true that everything runs more smoothly this way. But smoothness, it turns out, is a dubious virtue, since it’s often the unsmoothed textures of life that make it livable, helping nurture the relationships that are crucial for mental and physical health, and for the resilience of our communities.”

- “To approach your days in this fashion means, instead of clearing the decks, declining to clear the decks, focusing instead on what’s truly of greatest consequence while tolerating the discomfort of knowing that, as you do so, the decks will be filling up further, with emails and errands and other to-dos, many of which you may never get around to at all.”

Convenience culture seduces us into imagining that we might find room for everything important by eliminating only life’s tedious tasks. But it’s a lie. You have to choose a few things, sacrifice everything else, and deal with the inevitable sense of loss that results.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

Facing Finitude

- “(The original Latin word for “decide,” decidere, means “to cut off,” as in slicing away alternatives; it’s a close cousin of words like “homicide” and “suicide.”)”

- “Rather than taking ownership of our lives, we seek out distractions, or lose ourselves in busyness and the daily grind, so as to try to forget our real predicament.”

- “Why treat four thousand weeks as a very small number, because it’s so tiny compared with infinity, rather than treating it as a huge number, because it’s so many more weeks than if you had never been born?”

- “The exhilaration that sometimes arises when you grasp this truth about finitude has been called the “joy of missing out,” by way of a deliberate contrast with the idea of the “fear of missing out.” It is the thrilling recognition that you wouldn’t even really want to be able to do everything, since if you didn’t have to decide what to miss out on, your choices couldn’t truly mean anything.”

Becoming a Better Procrastinator

At any given moment, you’ll be procrastinating on almost everything.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “That smacks of self-help. (And heaven forbid that anyone might want to help themselves!)”

- “The real measure of any time management technique is whether or not it helps you neglect the right things.”

- “Perhaps you’re familiar with the extraordinarily irritating parable of the rocks in the jar, which was first inflicted upon the world in Stephen Covey’s 1994 book, First Things First, and which has been repeated ad nauseam in productivity circles ever since.”

- “Here the story ends—but it’s a lie. The smug teacher is being dishonest. He has rigged his demonstration by bringing only a few big rocks into the classroom, knowing they’ll all fit into the jar. The real problem of time management today, though, isn’t that we’re bad at prioritizing the big rocks. It’s that there are too many rocks—and most of them are never making it anywhere near that jar. The critical question isn’t how to differentiate between activities that matter and those that don’t, but what to do when far too many things feel at least somewhat important, and therefore arguably qualify as big rocks.”

- Principles for being a better procrastinator:

- “Principle number one is to pay yourself first when it comes to time.”

- “The second principle is to limit your work in progress.” Only work on three important things at once.

- “The third principle is to resist the allure of middling priorities.”

- “The good procrastinator accepts the fact that she can’t get everything done, then decides as wisely as possible what tasks to focus on and what to neglect. By contrast, the bad procrastinator finds himself paralyzed precisely because he can’t bear the thought of confronting his limitations.”

- “Buffett’s advice is different: he tells the man to make a list of the top twenty-five things he wants out of life and then to arrange them in order, from the most important to the least. The top five, Buffett says, should be those around which he organizes his time. But contrary to what the pilot might have been expecting to hear, the remaining twenty, Buffett allegedly explains, aren’t the second-tier priorities to which he should turn when he gets the chance. Far from it. In fact, they’re the ones he should actively avoid at all costs—because they’re the ambitions insufficiently important to him to form the core of his life yet seductive enough to distract him from the ones that matter most.”

- “The great irony of all our efforts to avoid facing finitude—to carry on believing that it might be possible not to have to choose between mutually exclusive options—is that when people finally do choose, in a relatively irreversible way, they’re usually much happier as a result.”

In a world of too many big rocks, it’s the moderately appealing ones—the fairly interesting job opportunity, the semi-enjoyable friendship—on which a finite life can come to grief.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

The Watermelon Problem

- “According to one calculation, by the psychologist Timothy Wilson, we’re capable of consciously attending to about 0.0004 percent of the information bombarding our brains at any given moment.”

The Intimate Interrupter

Why, exactly, are we rendered so uncomfortable by concentrating on things that matter—the things we thought we wanted to do with our lives—that we’d rather flee into distractions, which, by definition, are what we don’t want to be doing with our lives?

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “This is why boredom can feel so surprisingly, aggressively unpleasant: we tend to think of it merely as a matter of not being particularly interested in whatever it is we’re doing, but in fact it’s an intense reaction to the deeply uncomfortable experience of confronting your limited control.”

- “The overarching point is that what we think of as “distractions” aren’t the ultimate cause of our being distracted. They’re just the places we go to seek relief from the discomfort of confronting limitation.”

- “The way to find peaceful absorption in a difficult project, or a boring Sunday afternoon, isn’t to chase feelings of peace or absorption, but to acknowledge the inevitability of discomfort, and to turn more of your attention to the reality of your situation than to railing against it.”

Part II – Beyond Control

We Never Really Have Time

The obsessive planner, essentially, is demanding certain reassurances from the future—but the future isn’t the sort of thing that can ever provide the reassurance he craves, for the obvious reason that it’s still in the future.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “The cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter is famous, among other reasons, for coining “Hofstadter’s law,” which states that any task you’re planning to tackle will always take longer than you expect, “even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.” … It follows from this that the standard advice about planning—to give yourself twice as long as you think you’ll need—could actually make matters worse.”

- This is related to Parkinson’s Law.

- “It’s as if our efforts to be good planners don’t merely fail but cause things to take longer still.”

- “The fuel behind worry, in other words, is the internal demand to know, in advance, that things will turn out fine.”

- “You only ever get to feel certain about the future once it’s already turned into the past.”

- “So a surprisingly effective antidote to anxiety can be to simply realize that this demand for reassurance from the future is one that will definitely never be satisfied—no matter how much you plan or fret, or how much extra time you leave to get to the airport.”

- “You can’t know that things will turn out all right. The struggle for certainty is an intrinsically hopeless one—which means you have permission to stop engaging in it.”

- “What we forget, or can’t bear to confront, is that, in the words of the American meditation teacher Joseph Goldstein, “a plan is just a thought.” We treat our plans as though they are a lasso, thrown from the present around the future, in order to bring it under our command.”

You Are Here

- “Hence the old parable about a vacationing New York businessman who gets talking to a Mexican fisherman, who tells him that he works only a few hours per day and spends most of his time drinking wine in the sun and playing music with his friends. Appalled at the fisherman’s approach to time management, the businessman offers him an unsolicited piece of advice: if the fisherman worked harder, he explains, he could invest the profits in a bigger fleet of boats, pay others to do the fishing, make millions, then retire early. “And what would I do then?” the fisherman asks. “Ah, well, then,” the businessman replies, “you could spend your days drinking wine in the sun and playing music with your friends.””

- “The Catholic legal scholar Cathleen Kaveny has argued that the reason so many of them are so unhappy—despite being generally very well paid—is the convention of the “billable hour,” which obliges them to treat their time, and thus really themselves, as a commodity to be sold off in sixty-minute chunks to clients.”

Rediscovering Rest

To the philosophers of the ancient world, leisure wasn’t the means to some other end; on the contrary, it was the end to which everything else worth doing was a means.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “In this view of time, anything that doesn’t create some form of value for the future is, by definition, mere idleness. Rest is permissible, but only for the purposes of recuperation for work, or perhaps for some other form of self-improvement. It becomes difficult to enjoy a moment of rest for itself alone, without regard for any potential future benefits, because rest that has no instrumental value feels wasteful.”

- “Should vacations by the ocean, or meals with friends, or lazy mornings in bed need defending in terms of improved performance at work?”

- “The Latin word for business, negotium, translates literally as “not-leisure,” reflecting the view that work was a deviation from the highest human calling.”

- ““If the satisfaction of an old man drinking a glass of wine counts for nothing,” wrote Simone de Beauvoir, “then production and wealth are only hollow myths; they have meaning only if they are capable of being retrieved in individual and living joy.””

- “Social psychologists call this inability to rest “idleness aversion,””

- “Most people mistakenly believe that all you have to do to stop working is not work. The inventors of the Sabbath understood that it was a much more complicated undertaking.”

- “One need not be a religious believer to feel some of the deep relief in that idea of being “on the receiving end”—in the possibility that today, at least, there might be nothing more you need to do in order to justify your existence.”

- “There’s a less fancy term that covers many of the activities Setiya refers to as atelic: they are hobbies.”

- “There are positive side effects, like becoming more physically fit, but that’s not generally why people go on hikes. Taking a walk in the countryside, like listening to a favorite song or meeting friends for an evening of conversation, is thus a good example of what the philosopher Kieran Setiya calls an “atelic activity,” meaning that its value isn’t derived from its telos, or ultimate aim. You shouldn’t be aiming to get a walk “done”; nor are you likely to reach a point in life when you’ve accomplished all the walking you were aiming to do. “You can stop doing these things, and you eventually will, but you cannot complete them,” Setiya explains.”

- “The derision we heap upon the avid stamp collector or train spotter might really be a kind of defense mechanism, to spare us from confronting the possibility that they’re truly happy in a way that the rest of us—pursuing our telic lives, ceaselessly in search of future fulfillment—are not. This also helps explain why it’s far less embarrassing (indeed, positively fashionable) to have a “side hustle,” a hobbylike activity explicitly pursued with profit in mind.”

- “And so in order to be a source of true fulfillment, a good hobby probably should feel a little embarrassing; that’s a sign you’re doing it for its own sake, rather than for some socially sanctioned outcome.”

As long as you’re filling every hour of the day with some form of striving, you get to carry on believing that all this striving is leading you somewhere—to an imagined future state of perfection, a heavenly realm in which everything runs smoothly, your limited time causes you no pain, and you’re free of the guilty sense that there’s more you need to be doing in order to justify your existence.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

The Impatience Spiral

- “(The practice of inching toward the car in front while waiting at a red light, a classic habit of the restless motorist, is wholly self-defeating—because once things start moving again, you have to accelerate more slowly than you otherwise would, so as to avoid rear-ending the vehicle ahead.)”

- “(It has been calculated that if Amazon’s front page loaded one second more slowly, the company would lose $1.6 billion in annual sales.)”

- “You breathe a sigh of relief, and as you dive into life as it really is, in clear-eyed awareness of your limitations, you begin to acquire what has become the least fashionable but perhaps most consequential of superpowers: patience.”

- Siddhartha: “I can think, I can wait, I can fast.”

Staying on the Bus

In a world geared for hurry, the capacity to resist the urge to hurry—to allow things to take the time they take—is a way to gain purchase on the world, to do the work that counts, and to derive satisfaction from the doing itself, instead of deferring all your fulfillment to the future.

OLIVER BURKEMAN – FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS

- “As a result, most of us treat the problems we encounter as doubly problematic: first because of whatever specific problem we’re facing; and second because we seem to believe, if only subconsciously, that we shouldn’t have problems at all.”

- “Once you give up on the unattainable goal of eradicating all your problems, it becomes possible to develop an appreciation for the fact that life just is a process of engaging with problem after problem, giving each one the time it requires—that the presence of problems in your life, in other words, isn’t an impediment to a meaningful existence but the very substance of one.”

- The value of not finishing work

- “[The most productive academic writers] wrote in brief daily sessions—sometimes as short as ten minutes, and never longer than four hours—and they religiously took weekends off.”

- “If you’ve decided to work on a given project for fifty minutes, then once fifty minutes have elapsed, get up and walk away from it. Why? Because as Boice explained, the urge to push onward beyond that point “includes a big component of impatience about not being finished, about not being productive enough, about never again finding such an ideal time” for work. Stopping helps strengthen the muscle of patience that will permit you to return to the project again and again, and thus to sustain your productivity over an entire career.”

The Loneliness of the Digital Nomad

Happiness is only real when shared.

Christopher McCandless – Into The Wild

- “It’s a principle common to virtually all productivity advice that, in an ideal world, the only person making decisions about your time would be you: you’d set your own hours, work wherever you chose, take vacations when you wished, and generally be beholden to nobody. But there’s a case to be made that this degree of control comes at a cost that’s ultimately not worth paying.”

- “To borrow from the language of economics, Salcedo sees time as a regular kind of “good”—a resource that’s more valuable to you the more of it you command. (Money is the classic example: it’s better to control more of it than less.) Yet the truth is that time is also a “network good,” one that derives its value from how many other people have access to it, too, and how well their portion is coordinated with yours.”

- Telephones are useless if other people don’t have one and are free to call at the same time.

- “In fact, having large amounts of time but no opportunity to use it collaboratively isn’t just useless but actively unpleasant—which is why, for premodern people, the worst of all punishments was to be physically ostracized, abandoned in some remote location where you couldn’t fall in with the rhythms of the tribe.”

- “And in their more candid moments, digital nomads will admit that the chief problem with their lifestyle is the acute loneliness.”

- “Every gain in personal temporal freedom entails a corresponding loss in how easy it is to coordinate your time with other people’s. The digital nomad’s lifestyle lacks the shared rhythms required for deep relationships to take root.”

- “In 2013, a researcher from Uppsala in Sweden named Terry Hartig, along with several colleagues, elegantly proved the connection between synchronization and life satisfaction when he had the ingenious notion of comparing Swedes’ vacation patterns against statistics on the rate at which pharmacists dispensed antidepressants. One of his two central findings was unremarkable: when Swedes take time off work, they’re happier (as measured by their being less likely, on average, to need antidepressants). But the other was revelatory: antidepressant use fell by a greater degree, Hartig demonstrated, in proportion to how much of the population of Sweden was on vacation at any given time.”

- “Or to put things slightly differently, the more Swedes who were off work simultaneously, the happier people got. They derived psychological benefits not merely from vacation time, but from having the same vacation time as other people. When many were on vacation at once, it was as if an intangible, supernatural cloud of relaxation had settled over the nation as a whole.”

- “They suggest, he observed, that what people need isn’t greater individual control over their schedules but rather what he calls “the social regulation of time”: greater outside pressure to use their time in particular ways. That means more willingness to fall in with the rhythms of community; more traditions like the sabbath of decades past, or the French phenomenon of the grandes vacances, where almost everything grinds to a halt for several weeks each summer. Perhaps it even means more laws to regulate when people can and can’t work, like limits on Sunday store openings or recent European legislation banning certain employers from sending work emails out of hours.”

- “Bolt couldn’t help falling into line with Gay’s steps. And Bolt almost certainly benefited as a result: other research has indicated that conforming to an external rhythm renders one’s gait imperceptibly more efficient.”

- ““Totalitarian movements are mass organizations of atomized, isolated individuals,” wrote Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism.”

The Human Disease

- Some useful questions:

- “Where in your life or your work are you currently pursuing comfort, when what’s called for is a little discomfort?”

- “Are you holding yourself to, and judging yourself by, standards of productivity or performance that are impossible to meet?”

- “In what ways have you yet to accept the fact that you are who you are, not the person you think you ought to be?”

- “In which areas of life are you still holding back until you feel like you know what you’re doing?”

- “How would you spend your days differently if you didn’t care so much about seeing your actions reach fruition?”

- “Let your impossible standards crash to the ground. Then pick a few meaningful tasks from the rubble and get started on them today.”

- ““Dear Frau V.,” Jung began, “Your questions are unanswerable, because you want to know how to live. One lives as one can. There is no single, definite way…If that’s what you want, you had best join the Catholic Church, where they tell you what’s what.” By contrast, the individual path “is the way you make for yourself, which is never prescribed, which you do not know in advance, and which simply comes into being itself when you put one foot in front of the other.” His sole advice for walking such a path was to “quietly do the next and most necessary thing. So long as you think you don’t yet know what that is, you still have too much money to spend in useless speculation. But if you do with conviction the next and most necessary thing, you are always doing something meaningful and intended by fate.””

Appendix: Ten Tools for Embracing your Finitude

- “Any strategy for limiting your work in progress will help here (this page), but perhaps the simplest is to keep two to-do lists, one “open” and one “closed.””

- “A complementary strategy is to establish predetermined time boundaries for your daily work.”

- Cal Newport: Time-restricted work schedule.

- “Following the same logic, focus on one big project at a time (or at most, one work project and one nonwork project) and see it to completion before moving on to what’s next.”

- “It’s alluring to try to alleviate the anxiety of having too many responsibilities or ambitions by getting started on them all at once, but you’ll make little progress that way; instead, train yourself to get incrementally better at tolerating that anxiety, by consciously postponing everything you possibly can, except for one thing. Soon, the satisfaction of completing important projects will make the anxiety seem worthwhile—and since you’ll be finishing more and more of them, you’ll have less to feel anxious about anyway.”

- “But the great benefit of strategic underachievement—that is, nominating in advance whole areas of life in which you won’t expect excellence of yourself—is that you focus that time and energy more effectively. To live this way is to replace the high-pressure quest for “work-life balance” with a conscious form of imbalance, backed by your confidence that the roles in which you’re underperforming right now will get their moment in the spotlight soon.”

- “As a counterstrategy, keep a “done list,” which starts empty first thing in the morning, and which you then gradually fill with whatever you accomplish through the day.”

- Microsoft ToDo app.

- “Consciously pick your battles in charity, activism, and politics: to decide that your spare time, for the next couple of years, will be spent lobbying for prison reform and helping at a local food pantry—not because fires in the Amazon or the fate of refugees don’t matter, but because you understand that to make a difference, you must focus your finite capacity for care.”

- “You can combat this problem by making your devices as boring as possible—first by removing social media apps, even email if you dare, and then by switching the screen from color to grayscale.”

- “Choose devices with only one purpose, such as the Kindle ereader, on which it’s tedious and awkward to do anything but read.”

- “The habit proposed (and practiced) by the meditation teacher Joseph Goldstein: whenever a generous impulse arises in your mind—to give money, check in on a friend, send an email praising someone’s work—act on the impulse right away.”

- “So training yourself to “do nothing” really means training yourself to resist the urge to manipulate your experience or the people and things in the world around you—to let things be as they are.”

Read This Next

- Pathological Productivity

- Life is a Jar

- Atomic Habits Book Review

- My 10-day Vipassana Silent Retreat Experience

- Cal Newport Was Wrong

- What I Learned from Tracking my Mood for 1000 days

- The Do-Nothing Morning Routine Experiment

- Automate Your Finances

- Deep Work – Book Notes

- Looking Back On My 2-Month Podfast

- The Parallel Universes of Time and Money

Affiliate Links

- Four Thousand Weeks – Oliver Burkeman

- How to Live on 24 Hours a Day – Arnold Bennett

- Tao Te Ching – Lao Tzu (Translated by Stephen Mitchell)

- Siddhartha – Herman Hesse

- Walking – Erling Kagge

- Silence – Erling Kagge

- Atomic Habits – James Clear

- Stillness is the Key – Ryan Holiday