I started to draw some useful parallels between time and money. More specifically, between how we choose to spend and invest both resources. So what is the difference between spending and investing anyway?

Spending versus Investing

Spending is a short-term thing. It’s about allocating a resource without expecting to get much more than you put in.

| Money | Time |

| Doing groceries | Watching reality TV shows |

| Attending concerts | Doing house chores |

| Going to the movie theatre | Browsing social media |

Investing is the act of allocating resources, usually money, with the expectation of generating an income or profit.

Investopedia

Conversely, investing is a long-term thing. It is often conceptualized as the willingness to sacrifice the present for the future.

| Money | Time |

| Regularly contributing to a diversified portfolio | Building long-lasting relationships |

| Contributing to your employer’s pension plan | Exercising |

| Funding a startup company or picking stocks (risky) | Learning a new skill (post-secondary education) |

The line between spending and investing is not always clear-cut. Consider the classic debate of whether it’s best to rent or buy a home. Renting is clearly a form of spending. You pay X amount of money to be able to live there for another month (short-term). Unfortunately, buying a house isn’t as simple. Some of the money you pay each month towards your mortgage goes towards your home’s equity while another portion goes towards paying off interest. The interest portion of your mortgage payment is a form of spending. The same can be said about the many other expenses that come with owning a home such as paying property tax and paying for the basic upkeep. Historically, the average real estate value increased over time so it makes sense to think of the value of your home as an investment (not saying it’s a good or a bad one).

Compounding

The purpose of the rent versus buy example was to illustrate the nuance that one thing can count as both spending and investing. The key differences are the expected returns and time scale. For spending, the time scale is short and the expected return is roughly the same as the cost. For investing, the expected returns are greater than the cost (for good investments) at the expense of having to wait to collect the profit. There is also a notion of compounding when it comes to investing. The returns on investments (ROI) tend to grow exponentially whereas the value you gain from spending your time or money is much more linear.

You can see from the graph above that linear growth (blue line) often outperforms exponential growth (red curve) in the short term. However, there will always be a tipping point where the exponential will greatly outperform the linear curve. It all depends on the time horizon.

When spending, it’s still worthwhile to try to get more (subjective) value than the initial cost but this value won’t grow exponentially like a typical investment. A money-example of good spending for me was to get myself a proper bike when I moved to Ottawa. I paid around 700$ for it. I certainly paid it back just in gas savings (probably more). That was a good purchase but the value obtained from my bike is roughly linear (with the exception of being active which tends to slow down the exponential decay that accompanies age and a sedentary lifestyle).

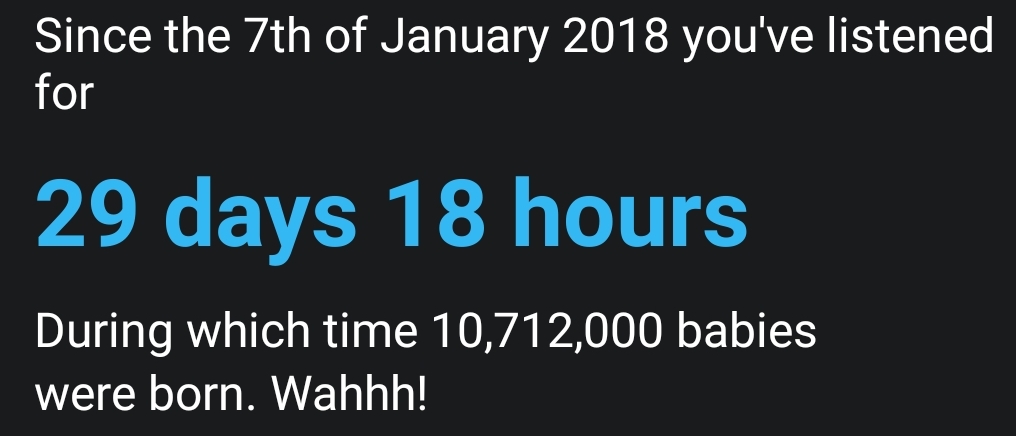

A time-example of bad spending was getting off the social media train in 2018. I was not getting enough value (maybe even a net negative) for the immense amount of time I spent on these platforms. Since then, I try (but fail often) to be much more intentional with my social media usage. I didn’t want to deprive myself of some of the obvious benefits on the table so I listened to Cal Newport’s advice and wrote down what I wanted to get out of these technologies and tailored my usage accordingly. For example, I allow myself to watch anything on YouTube as long as I searched for the video or it was in my watch later list. This reduces the risk of impulsivity and trying to keep up with the nearly infinite stream of interesting content. Most of the videos, tv shows, and books that were strongly recommended to me lost their appeal shortly after. Therefore, only consuming information that withstood the test of time can help us increase our spending quality.

We are finite beings living in a near infinite world.

Entertainment versus Learning

Another useful framework is to think of your information consumption as a form of spending and investing. Let’s draw a distinction between consuming information for entertainment versus for learning.

When you consume information for entertainment (social media, TV shows, fiction books, etc), you are essentially spending your time and energy. You hope that the benefits from watching the latest TV show will be roughly equal to the time and energy spent watching it. Benefits of watching a TV show could include: being able to gossip about the show with your social circle, learn a thing or two, feel emotions, and forget for 48 minutes about the other 49 things that your conscience is telling you would be a better use of your time. I’ve found that I get the most value from entertainment activities when they are performed in a social setting. Watching a sporting event with friends is almost a guaranteed net positive for me. The social aspect of the activity is an investment in my long-term friendships while the event itself provides significant value in the short term.

When you consume information for learning (reading, podcasts, studying, etc), you are essentially investing your time and energy. It requires more effort to consume information for learning rather than for entertainment. In other words, there tends to be a greater cost to learning than to passively consume entertainment. The reason we sacrifice ourselves to learn things is that we hope that the benefits of the newly acquired skill will compound the long term. Of course, this assumes that the learning was successful and that the new knowledge will have useful applicability. If the non-fiction books you read don’t change your thoughts or behaviour, then you are essentially spending your time and energy. You are practically using self-help as a form of entertainment.

Savings Rate

Now, there is nothing wrong with entertainment. It’s sad that the previous sentence needs to be written. The current productivity-obsessed culture is to blame for the guilt that too often comes up while doing something that we enjoy without having a master plan of growing or monetizing the activity (p.s. You are particularly at risk of feeling this way if you’re reading this article). The good news is that you don’t need to choose between fiction and non-fiction or between reality tv and documentaries. In fact, a more useful endeavour is to try to figure out your savings rate.

The Pay Yourself First principle presented in The Wealthy Barber says that we should automatically invest 10% of our income for the long term before we spend our paychecks on anything else. Most personal finance gurus vouch for this guideline in addition to contributing to your employer’s pension plan amongst other things (see The Waterfall Method). I think the rough 10-30% savings rate that applies to money can guide our spending-to-investing ratio for information consumption.

Let’s assume that the average day has 16 waking hours. 10% of 16 hours is 1.6 hours. Thus, if we apply the Pay Yourself First principle to our time, then we should regularly invest the first 90 minutes of our days. Doing it first thing in the morning is ideal because, like money and water, time seems to naturally follow the path of least resistance if left unattended (see Parkinson’s law for more on this). Taking care of the big rocks early in the day takes the pressure off to budget and manage your time for the rest of the day. The same can be said about money. You can spend guilt-free when you know that you took you’ve checked off the things that really matter (the 80-20 rule also applies here). The rest is just noise.

| Time Savings Rate | Daily Investment Time |

| 10% | 1.5 hours |

| 20% | 3 hours |

| 30% | 4.5 hours |

From experience, it is much harder than it looks to set aside time on a daily basis to attend to the important but not urgent items on our infinitely long to-do lists (see Quadrant II activities from the Eisenhower box). Realistically, we have around 5 hours in a day where we get to choose how to spend our time (if we’re lucky). That is why the savings rate is a percentage and not a fixed amount of time. If you only have 3 hours of “free time”, then a 15% savings rate equates to roughly 30 minutes. There are countless things you could be doing during these precious minutes. I included some of my go-to activities in the table below. You might find value in The 5 AM Club by Robin Sharma.

| Body | Social | Mind | Career |

| Walk or bike to commute | Boardgame nights | Long walks | Read |

| Home workouts & fitness classes | Call friends and family | Meditation | Duddhawork |

| Sports | Attend to my relationship | Journaling | Education |

There is no secret formula. Life is messy. We’re not robots. You will struggle with being consistent. It will require discipline. But as Jocko Willink says: “Discipline equals freedom“. You’ll have to Duddhawork! I try to keep the two following pieces of information in mind to work smart instead of strictly working hard. First, our focus tends to operate on 90-minute intervals (ultradian cycles). Second, I try to engage in deep work for the period of time I am investing. This way, I can take care of business and feel good the rest of the day without always defaulting to “the grind”. Willpower doesn’t work.

Being busy is a form of laziness – lazy thinking and indiscriminate action. Being busy is most often used as a guise for avoiding the few critically important but uncomfortable actions.

Tim Ferris

Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is another interesting way to approach the resemblances between investing money and investing time. More specifically, I wanted to focus on how we can tailor our sources of information to our specific goals and time horizon.

The true cost of a book is the time spent reading it.

Most of us consume information with the goal to improve our quality of life. As far I know, there isn’t much research to point to when it comes to which sources of information are best to reach this goal. However, traditional wisdom proposes a loose hierarchy of information quality when it comes to learning. It goes something like this:

Books ⇒ Audiobooks ⇒ Blog posts & Podcasts ⇒ YouTube videos ⇒ Social media posts

The issue is that most of us don’t allocate our time accordingly. Instead, we default to the path of least resistance and our consumption looks something like this:

Social media posts ⇒ YouTube videos ⇒ Blog posts & Podcasts ⇒ Audiobooks ⇒ eBooks & Books

We have it backwards. We mindlessly and impulsively spend the bulk of our precious time on low-quality sources of information. Getting your information intake from social media is the equivalent of day trading in the financial world. It’s speculative, it’s addicting, it’s a distraction from doing the things that matter, and it usually comes with higher fees and more taxes (opportunity cost and the price of distractions). It is Naval Ravikant who first introduced me to this idea. He refers to shallow learning as “dopamine-snacks“. Blogs and podcasts are better but they are often too shallow to lead to long-term behaviour changes. They serve as great introductions to topics that can be explored more fully through books or courses. I put audiobooks below eBooks and physical books since they can be consumed passively. Furthermore, it tends to be more difficult to take notes with audiobooks and podcasts.

| Social Media | Youtube | Podcast | Books | |

| Estimated Daily Minutes | 15 | 20 | 30 | 3 |

It would be cool to be able to exactly quantify our time allocation to each “asset class”. I look forward to the day where the social media companies make these statistics available and obvious like the burnt lungs on packs of cigarettes.

The Big Picture

The idea is to match your time allocation and total time spent consuming information to your goal. Today, at 25 years old, my goal is to learn as much as I can since the acquired principles have time to compound. I feel as though there are many low-hanging fruits left to pick by reading books. Of course, there will come a point of diminishing returns for consuming information with the goal of learning. I absolutely identify as a lifelong learner. That said, I can envision a day where my life is less future-oriented and my goal is to live simply, to entertain myself, and to take care of my body and the people around me.

The function of self-actualization is to erase itself.

Abraham Maslow

Read This Next

- Atomic Habits

- The Wealthy Barber – Book Notes

- Life is a Jar

- New Year’s Resolution ➡️ New Month’s Resolutions

- What is your Investment Goal?

- Millionaire Teacher by Andrew Hallam (2nd Edition)

- What I Learned from Tracking my Mood for 1000 days

- My 10-day Vipassana Silent Retreat Experience

- The Do-Nothing Morning Routine Experiment

- Three Questions for Success

Affiliate Links

- Take effective book notes – Readwise

- Invest automatically – Wealthsimple Invest Robo-Advisor

- Build your own portfolio – Wealthsimple Trade

- Save money and make a little – EQ Bank High-Interest Savings Account

- The Compound Effect – Darren Hardy

- Digital Minimalism – Cal Newport

- The 80/20 Principle – Richard Koch

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People – Stephen R. Covey

- The 5 AM Club – Robin Sharma

- Discipline Equals Freedom – Jocko Willink

- Deep Work – Cal Newport

- Willpower Doesn’t Work – Benjamin P. Hardy

- Almanack of Naval Ravikant – Eric Jorgenson (Free Book)

- Make It Stick – Peter C. Brown & Henry L. Roediger III

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]