Takeaways

- “Raising achievement is important because it matters for individuals and society. If you achieve at a higher level, you live longer, are healthier, and earn more money. For those with only a high school diploma, the standard of living in the United States is lower today than it was in 1975; for those with degrees, it is 25 to 50% higher.” (Dylan William)

- “To do this, we must have a shared vision of the primary purpose of grades: to provide communication in summary format about student achievement of learning goals. This requires that grades be accurate, meaningful, consistent, and supportive of learning” (Ken O’Connor)

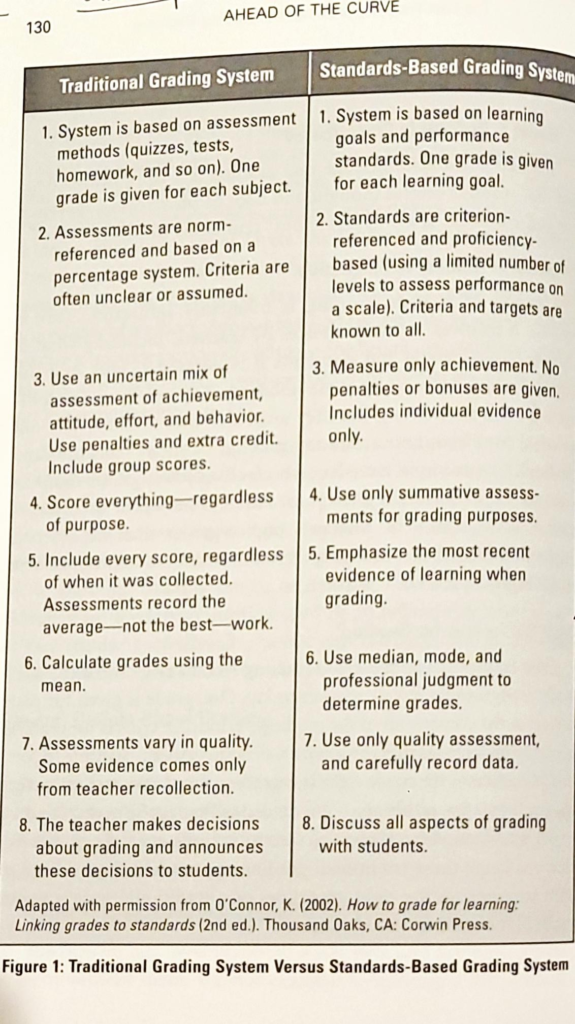

- Our assessments should be criterion-reference instead of norm-referenced. Growing Success needs to update its choice of words for the French version.

- We measure teacher effectiveness from student learning. It’s a shame that we don’t spend more time in collaboration teams evaluating each other’s performance. I wish we could watch and learn from our colleagues and give each other feedback. I wish we had time to review each formative assessment in detail as a team and change our teaching accordingly.

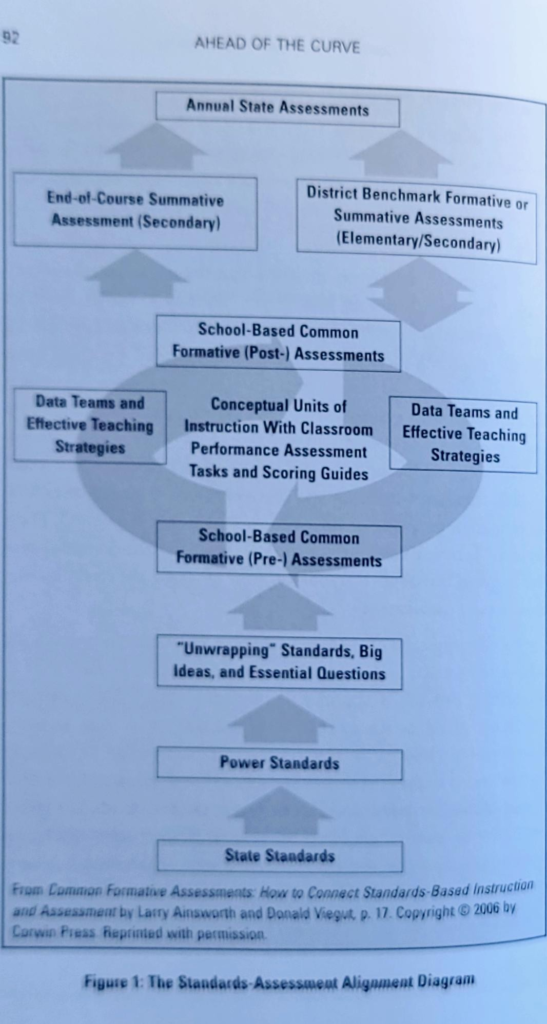

- “Douglas Reeves (2004) refers to this dilemma as the “over-testing and under-assessing” of students (p. 71). Richard DuFour (2005) has aptly named this the DRIP syndrome: Schools have become “data rich but information poor” (p. 40). School systems across the country are realizing the need for a definite process to analyze assessment results and use that data to inform instruction.”

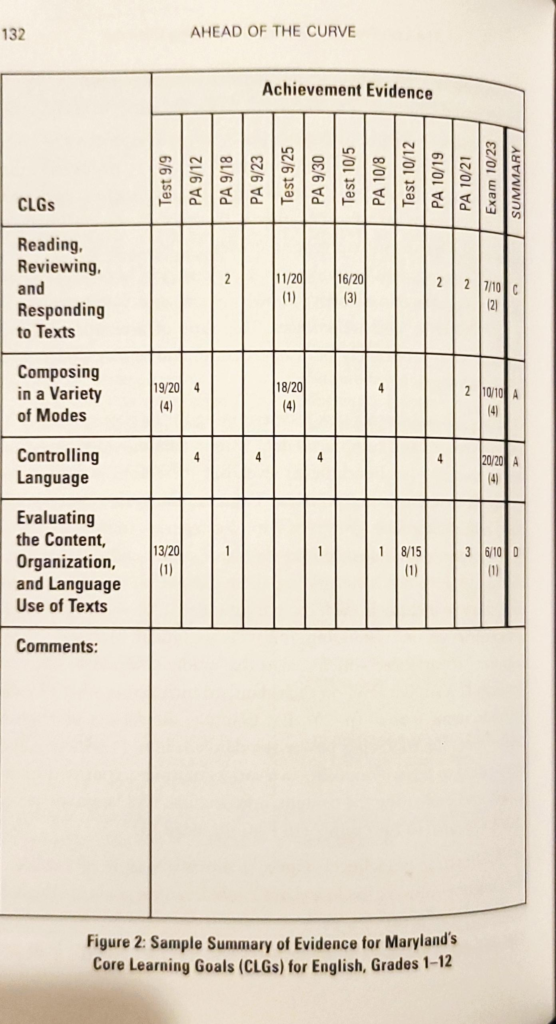

- Our school board needs to switch to evaluating the standards directly instead of the four competencies. Adopting an evidence record such as the ones displayed in the Marzano and O’Connor chapters would be a game changer. It’d allow us to do triangulation transparently.

- I’m going to show even more samples of projects to my students. In math, it’s usually more straightforward. The students know they need to get the right answers and communicate effectively.

- Assessment

- Power standards

- Build quality assessments that allow multiple opportunities to display mastery of those standards. Ideally spaced out in time and diversified assessment methods (triangulation).

- Design instructional units to teach the power standards.

- Tons of formative assessments. Review the evidence as a team. Modify instruction accordingly.

- Assess summatively and report grades in a transparent and meaningful format.

- “We cannot dependably assess that which we have not defined.” — Rick Stiggins

- We need to invest in a question bank for our math department. This would allow for more quality student practice and randomized assessments. We could finally allow students retakes without drowning us in extra work. A quality question bank would also ensure that new teachers create quality assessments.

- Percentages depend on difficulty. 10/10 on level two questions is still a level two.

- “It has been demonstrated both empirically and conceptually that scoring assessments using a 100point or percentage scale typically is not sensitive to learning over time (Marzano, 2002, 2006). Specifically, when teachers design their assessments using the 100-point scale, they construct and weigh items on different tests in highly subjective ways. Consequently, a student who receives a score of 80 on one test and 90 on another has not necessarily gained 10 points in terms of knowledge. That gain might be a simple artifact of the teacher changing his or her scheme for constructing and weighing test items. Figure 2 shows a scale that is sensitive to learning over time.”

- “Specifically, each formative assessment must have items or tasks that students must learn for level 2.0, level 3.0, and level 4.0 of the scale. Level 2.0 and level 3.0 elements are explicitly stated in the scale.”

- Our assessments don’t need to be psychometrically bulletproof. Especially not for formative assessments. Fast and dirty is better than slow and clean when it comes to formative assessment.

- “This is a fair challenge, and the answer is not that a 10-item test designed by teachers, with results returned in hours rather than weeks, is superior to a 100-item test designed by professional test writers. The answer, rather, is that school leaders must choose which error has the least risk for their students.”

- “If these findings are so obvious, why do schools so rarely give priority to literacy? Why is the prevailing model in school schedules the presumption that all subjects are of equal value and thus deserve equal time?”

- “It is only a matter of tradition that meetings are reserved for announcements. Leaders in collaborative cultures dispense with the formalities and invest time in genuine collaboration.”

Favourite Chapters

- Chapter 5 Designing a Comprehensive Approach to Classroom Assessment Robert J. Marzano

- Chapter 6 The Last Frontier: Tackling the Grading Dilemma Ken O’Connor

- Chapter 9 Content Then Process: Teacher Learning Communities in the Service of Formative Assessment Dylan Wiliam

- Chapter 11 Challenges and Choices: The Role of Educational Leaders in Effective Assessment Douglas Reeves

- Epilogue Once Upon a Time: A Tale of Excellence in Assessment Richard DuFour

Book Highlights

Introduction: From the Bell Curve to the Mountain: A New Vision for Achievement, Assessment, and Equity (Douglas Reeves)

- “The underlying logic of the bell curve structure is simply the wrong model for evaluating educational achievement. It is the worst of all possible worlds: It fails to acknowledge good performance and gives unearned accolades to poor performance. Those who fail to “beat” their neighbors are labeled inferior, even when proficient, and those who do beat their neighbors are labeled superior, no matter how inadequate their performance.”

- “What is the evidence that we have to justify continuation of current practice? What is the risk of trying new practice? What is the risk of continuing current practice?”

Chapter 1: Using Assessments to Improve Teaching and Learning (Thomas R. Guskey)

- “If teachers find no obvious problems with the item or then they must turn their attention to their teaching. When as many as half the students in a class answer a clear question incorrectly or fail to meet a particular criterion, it is not a student learning problem-it is a teaching problem. Whatever strategy the teacher used, whatever examples were employed, or whatever explanation was offered, it simply did not work. Analyzing assessment results in this way means setting aside some very powerful ego issues. Many teachers may initially say, “I taught them. They just didn’t learn it!” But with further reflection, most recognize that effectiveness in teaching is not defined on the basis of what they do as teachers. Rather, it is defined by what their students are able to do. If few students learned what was taught, can it be said that the teaching was effective? Can effective teaching take place in the absence of learning? Certainly not.”

- “Occasionally, teachers express concern that if they take class time to offer corrective instruction, they will need to sacrifice curriculum coverage. But this need not be the case. Initially, corrective work must be done in class, under the teacher’s direction. Efforts to involve students in corrective instruction once per week or during special study sessions conducted before or after school rarely succeed (see Guskey, 1997). In addition, teachers who ask students to complete corrective work independently, outside of class, generally find that those students who most need to spend time on corrective work are the least likely to do so. For these reasons, early instructional units will require more time, typically an extra class period or two.”

Chapter 2: Involving Students in the Classroom Assessment Process (Anne Davies)

- “This second type of feedback needs to come at the end of the learning. It is summative. It tells the learner how she or he has performed compared to others (norm-referenced) or in relation to what was to be learned (criterion-referenced). Evaluative feedback is communicated using letters, numbers, checks, or other symbols; it is encoded. Students who receive evaluative feedback usually understand whether or not they need to improve. However, unless students can decode the evaluative feedback, they may not have enough information to understand how to improve.”

- “In the past, there was an assumption that such evaluation was best done externally, with tests and other forms of evaluation created and monitored by outside sources. Assessment Reform Group’s research (2006) has revealed, however, that when a teacher’s professional judgment regarding the quality of student work is based on knowledge arising from the conscientious development and application of consistent criteria for summative evaluation, the teacher’s judgments are likely to be more valid and reliable than the results of external tests. It is essential that evidence of learning be triangulated (collected from multiple sources and in multiple forms) and collected over time. And when teachers work together and develop clearly specified criteria that describe progressive levels of competence and procedures for using criteria to evaluate student work, they are more able to reliably assess and evaluate a greater range of classroom work. Looking at a greater range of student work (including both qualitative and quantitative evidence) as they learn to apply shared criteria can increase the validity of teachers’ judgments and limits the need for external evaluation. This process helps teachers become more confident and better able to make independent judgments (Assessment Reform Group, 2006; Sadler, 1989).”

- “Sometimes students do not know enough to set good criteria, so teachers inform the criteria-setting process by showing samples or models or by waiting until later in the learning process to co-construct criteria.”

- “Samples that show successive changes in quality help students understand how learning develops over time. Teachers may share several samples from the same student that show the student’s initial ideas, early drafts, and the finished piece.”

Chapter 3: Assessment for Learning: An Essential Foundation of Productive Instruction (Rick Stiggins)

Quality assessment represents a necessary but insufficient condition for productive assessment.

Rick – Stiggins

- “I continue to honor my professional heritage: I believe more strongly than ever that assessment results must be accurate in all contexts. Inaccurate data leads to counterproductive instructional decisions, and thus it is harmful to students. However, I have come to realize that truly productive assessment cannot merely be about qualities of instruments and the attributes of their resulting scores. Rather, it must also be about the impact of that score on the learner. In other words, I have come to see that students also read, interpret, and, most importantly, act on the data we generate with our assessments about their achievement. They make crucial decisions based on those data. In fact, I have come to understand that the decisions they make as users of assessment results exert far greater influence on their success as learners than do the decisions made by the adults-the parents, teachers, administrators, and policymakers-around them.”

- “To create quality assessments, educators must do the following:

- Start with a clear purpose for assessment; a sense of why we are assessing.

- Include a clear achievement target; a vision of what we need to assess.

- Design an assessment that accurately reflects the target and satisfies the purpose.

- Communicate results effectively to the intended user(s).”

- “As instruction unfolds daily in the classroom, the key question to be answered with data is this: “What comes next in the learning?” The decision-makers are students and teachers. The information these decision-makers need is continuous evidence of how each individual student is doing on her or his learning journey towards each standard. Both student and teacher must know where the learner is now, how that compares to ultimate learning success, and how to close the gap between the two. Students must not be wondering if they will succeed-only when they will succeed.”

- “We cannot dependably assess that which we have not defined. These days, we start target definitions with state standards or local adaptations of those standards.”

- “Include enough items to sample appropriately student knowledge so as to gather enough evidence to lead to a confident conclusion about achievement without wasting time gathering too much.”

- “A quality assessment gathers enough information to lead to a confident conclusion, but it does not gather too much information. So how much is enough evidence? How many test items? How many performance tasks or essay exercises? The context determines the answers to these questions. The higher the stakes, the more certain we must be, and the more data we must gather. The more complex the target, the more evidence we may need. The more evidence a task provides, the fewer tasks we need.”

- “In the opening to this chapter, I argued that quality assessment represents a necessary but insufficient condition for productive assessment. I hope it is clear now specifically what we mean by quality, and how to achieve it. The second active ingredient in productivity is the effective use of the assessment process and its results to help students advance their learning with enthusiasm and feel in control of their learning as they attain new levels of proficiency.”

- “With assessment for learning, all students can experience the ongoing joy and optimism that comes from expecting to succeed and living up to that expectation.”

- PERMA model

- Dan Pink’s research on motivation (Drive)

- “The student’s role in assessment of learning is as it always has been: to study hard and strive for the highest scores and grades; that is, demonstrate competence. But in assessment for learning, the student’s role is to strive to understand what success looks like and to use each assessment to try to understand how to do better the next time.”

- “Finally, we help our students become increasingly efficacious when we show them how to close the gap between where they are now and where we want them to be in their learning (Sadler, 1989).”

Productive assessment leaves students feeling in control and optimistic, even if they do not perform well. Counterproductive assessment robs students of that sense of control, resulting in a pervasive sense of hopelessness.

Rick Stiggins

Chapter 4: Common Formative Assessments: The Centerpiece of an Integrated Standards-Based Assessment System (Larry Ainsworth)

- “There is also the question of the frequency of assessments: How often should educators assess to determine student learning? Assessment experts (Marzano, Stiggins, Black, Wiliam, Popham, and Reeves) agree that numerous short assessments given over time provide a better indication of a student’s learning than one or two large assessments given in the middle and at the end of the grading period (Ainsworth & Viegut, 2006). The true value of assessment is its ability to help educators make accurate and timely inferences about student progress so that they can modify instruction accordingly.”

- “Douglas Reeves (2004) refers to this dilemma as the “over-testing and under-assessing” of students (p. 71). Richard DuFour (2005) has aptly named this the DRIP syndrome: Schools have become “data rich but information poor” (p. 40). School systems across the country are realizing the need for a definite process to analyze assessment results and use that data to inform instruction.”

- “State test data focus on comparisons between groups of students, rather than on individual student gains from one assessment to the next. The feedback from most state assessments is not specific enough to pinpoint the unique learning needs of individual students. Even though state test results provide a “snapshot” of student understanding, when looked at in isolation, they do not provide the “photo album” of student understanding (gathered over time) that can truly represent what students know and are able to do.”

- “This is not to minimize the role of external assessments in favor of internal assessments only. Both assessments of and for learning are important (Stiggins, 2002), and “while they are not interchangeable, they must be compatible” (NEA, 2003, p. 7). The key to maximizing the usefulness of both types is to intentionally align assessments of and for learning so that they are measuring the same student progress.”

- “By collaboratively designing the summative assessment before any actual instruction takes place, educators are “beginning with the end in mind.” Knowing-in advance-what the students will need to know and be able to do on the summative assessment will most definitely impact instruction. To measure student progress along the way, educators can administer shorter formative assessments that are closely aligned to their summative assessment. The formative assessment results, when analyzed carefully, will provide the educators with “predictive value” as to how their students are likely to do on the subsequent assessments. The results will allow them to more accurately diagnose student learning needs to determine what instructional modifications are needed.”

- “Power Standards are not all that we teach; rather, they represent those prioritized learning outcomes that are absolutely essential for all students to know and be able to do.”

- “To meet this “cognitive demand,” educators do not teach to the test, but rather they teach to the skills that their students will need to be successful (Popham, 2003).”

- “Educators need to develop their own assessment literacy by attending professional development sessions that allow them to experience writing assessment items matched to the unwrapped concepts and skills they are targeting. Creating quality assessment items is a stimulating challenge and demanding work. Once educators understand the process through hands-on experience, they inevitably discuss among themselves ways to accelerate the item-writing part of the process. Busy as they are, they realize the value of “working smarter, not harder” by looking for assessment items from outside sources.”

- “There are, however, definite time-saving devices that educators can utilize. School systems are recognizing the value of establishing their own teacher-created “banks” of common formative assessment items. Once educators learn how to write quality assessment questions that meet the criteria for well-written items, they can “deposit” those items into the school or district bank as they continue creating them or adapting them from other sources. Some of the best sources for such items are state education websites that post released assessment items from prior state assessments. These items can be useful for studying formatting, standards vocabulary, and the varying levels of rigor found within the assessments. Another source that may prove helpful is the assessment or evaluation component of the school- or district-adopted textbook series. Once educators have improved their individual and collective assessment literacy by understanding the criteria for well-written assessment items, they are in a much better position to select or modify items from external sources to meet their specific purposes. (For more information on writing quality assessment items, see Haladyna, 1997; Popham, 2003; Stiggins, 1997; Stiggins, Arter, Chappuis, & Chappuis, 2004.)”

- “Educators need to realize that the research rationale for formative assessment is based on short-cycle assessments (a term attributed to British researchers Dylan Wiliam and Paul Black)…. If the results don’t get back in time for teachers to adjust instruction for the students being assessed, then it’s not formative assessment” (2006, p. 86).”

Educators do not teach to the test, but rather they teach to the skills that their students will need to be successful.

James W. Popham – Test Better, Teach Better

Chapter 5: Designing a Comprehensive Approach to Classroom Assessment (Robert J. Marzano)

Feedback must provide students with a way to interpret even low scores in a manner that does not imply failure

Robert J. Marzano

- “A meta-analysis by Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, Kulik, and Morgan (1991) that reviewed findings from 40 studies on classroom assessment found that simply telling students they were correct or incorrect in their answers had a negative effect on their learning, whereas explaining the correct answer and/or asking students to continue to refine their answers was associated with a gain in achievement of 20 percentile points.”

- “Their recommendation is that teachers should systematically use classroom assessments as a form of feedback. Indeed, they found a positive trend for assessment even up to 30 assessments in a 15week period of time. This same phenomenon was reported by Fuchs and Fuchs (1986) in their meta-analysis of 21 controlled studies. They reported that providing two assessments per week results in a percentile gain of 30 points.”

- “Measurement theory is based on the principle that an assessment for which only one score is provided for student achievement measures a single dimension or trait of that achievement (Hattie, 1984, 1985; Lord, 1959).”

- “Clearly, standards documents as they are currently written mix multiple dimensions or traits in their descriptions of what students should know and be able to do. To remedy this situation, standards documents can be reconstituted to articulate a small number of “measurement topics” that address single dimensions, or dimensions that are closely related in terms of student understanding. Consider Figure 1 (pages 110-111), which contains sample measurement topics for language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies”

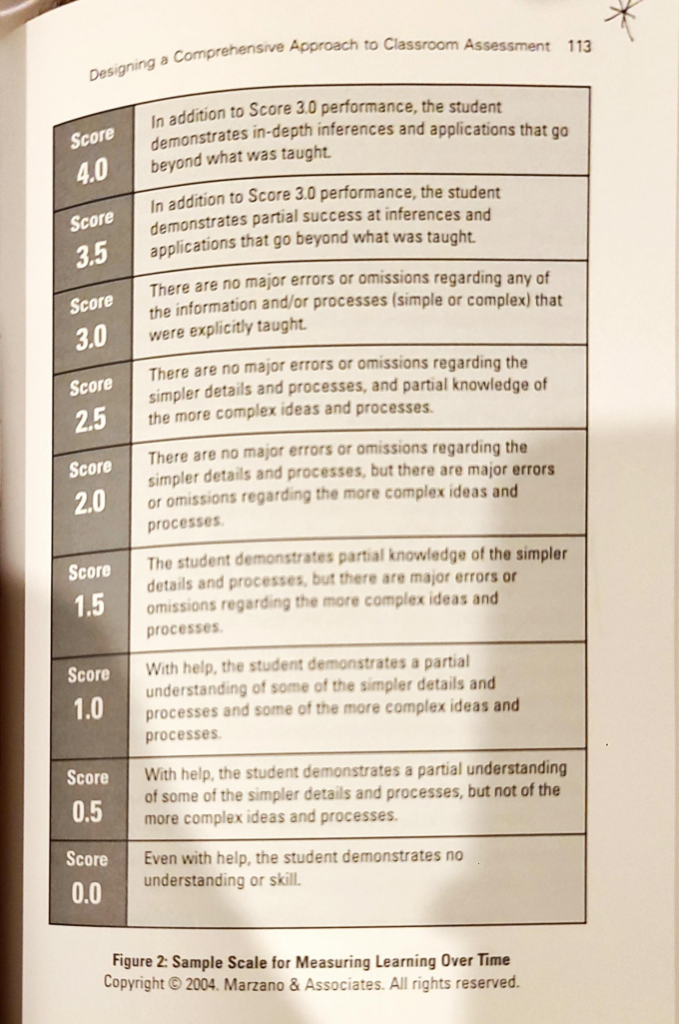

- “It has been demonstrated both empirically and conceptually that scoring assessments using a 100point or percentage scale typically is not sensitive to learning over time (Marzano, 2002, 2006). Specifically, when teachers design their assessments using the 100-point scale, they construct and weigh items on different tests in highly subjective ways. Consequently, a student who receives a score of 80 on one test and 90 on another has not necessarily gained 10 points in terms of knowledge. That gain might be a simple artifact of the teacher changing his or her scheme for constructing and weighing test items. Figure 2 shows a scale that is sensitive to learning over time.”

- “Specifically, each formative assessment must have items or tasks that students must learn for level 2.0, level 3.0, and level 4.0 of the scale. Level 2.0 and level 3.0 elements are explicitly stated in the scale.”

- “If students answer all items correctly, they receive a score of 4.0. If they answer all level 3.0 and 2.0 items correctly, and get partial credit on the level 4.0 item, they receive a score of 3.5. If students answer all level 3.0 and 2.0 items but miss the level 4.0 item, they receive a score of 3.0. If students answer all level 2.0 items correctly, receive partial credit for the level 3.0 items, but do not answer the level 4.0 items correctly, they receive a score of 2.5, and so on.”

“Knowledge gain,” then, is the currency of student success in an assessment system that is formative in design. Focusing on knowledge gain is also a legitimate way to recognize and celebrate success.

Robert J. Marzano

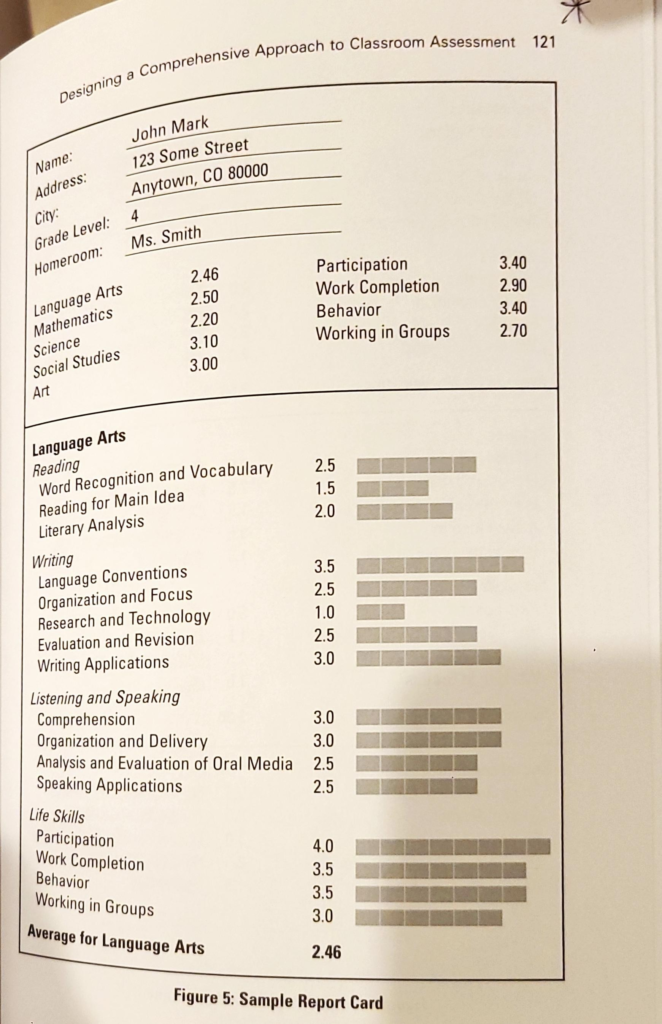

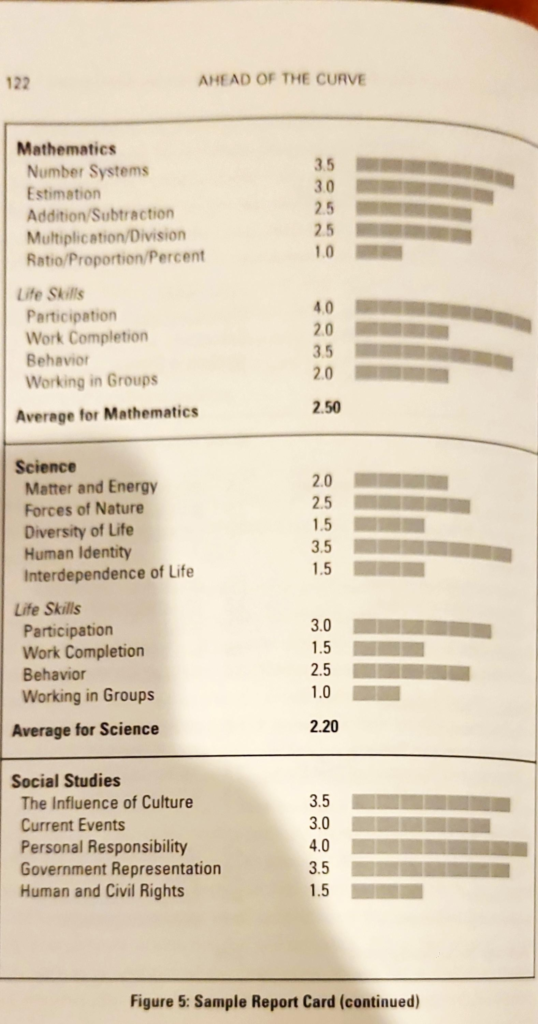

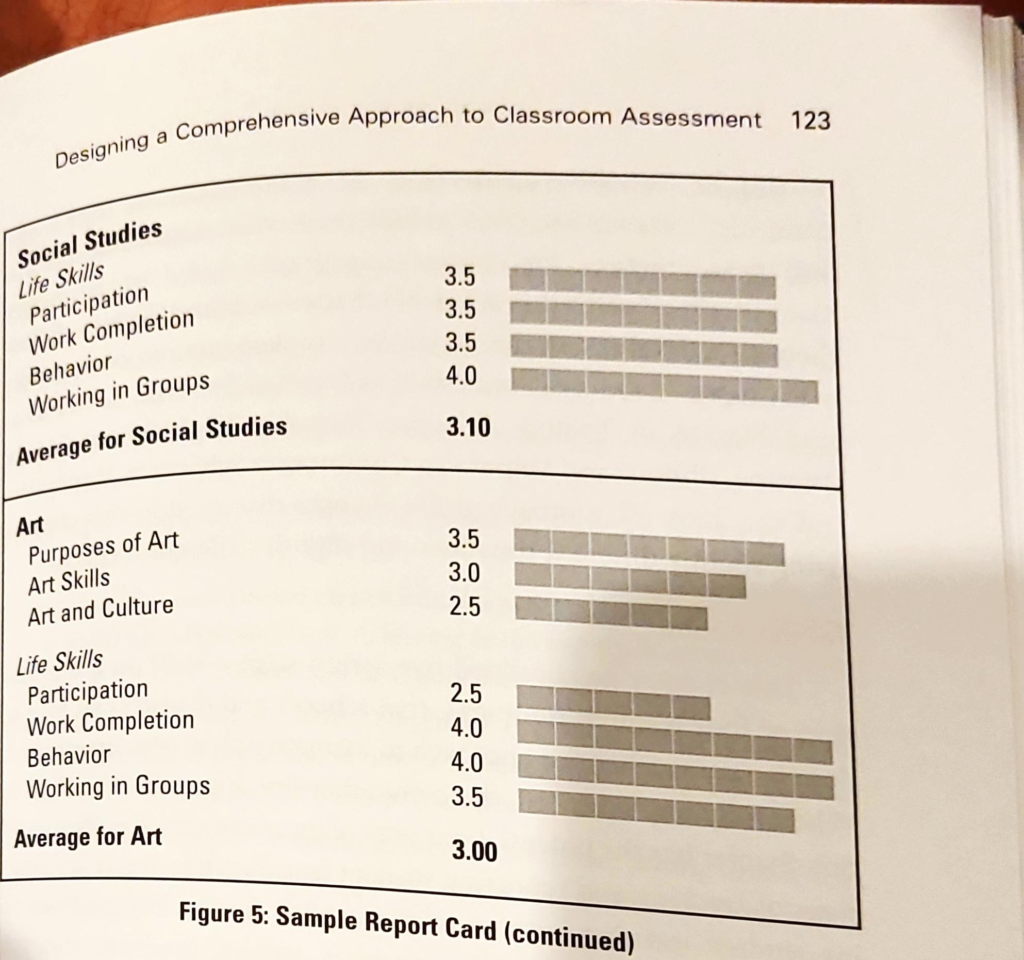

- “Constructing measurement topics using the scale depicted in Figure 2, and then designing and implementing report cards, such as the one shown in Figure 5, is no small task and is not accomplished in one fell swoop. Initial steps in the design of measurement topics are best undertaken by a small group of teachers—the “vanguard group” (see Marzano, 2006)-who are willing to work through the intricacies of such a task. This is in contrast to opening up the task to all teachers whether they wish to participate or not. The complexity of the work when foisted on unwilling participants who already feel overworked can doom the project to failure. A vanguard group is also the best vehicle for experimenting with the design and scoring of formative assessments using measurement topics, the computer software necessary to keep track of formative assessments, and new practices for constructing grades based on formative assessments. Finally, it is advisable that schools and districts follow their own timelines in the design and implementation of measurement topics.”

Chapter 6: The Last Frontier: Tackling the Grading Dilemma (Ken O’Connor)

Grading of student learning is inherently subjective.

Ken O’Connor

- “To do this, we must have a shared vision of the primary purpose of grades: to provide communication in summary format about student achievement of learning goals. This requires that grades be accurate, meaningful, consistent, and supportive of learning”

- “Grading of student learning is inherently subjective. This is because it involves so many choices by teachers, including what is assessed, what criteria and standards it is assessed against, and the extent to which students meet the standards. Teachers must not apologize for this subjectivity, but they must also ensure that it does not translate into bias, because faulty grading damages students (and teachers). For example, a student who receives lower grades than she deserves might decide to give up on a certain subject or drop out of school, while a student who gets higher grades than he deserves might find himself in a learning situation where he cannot perform at the expected level of competence.”

- “Thus, standards need to be organized into manageable groups of 7 to 15 categories. In some districts, these categories are called “power standards”: the standards that matter the most. When determining these categories, districts/schools should try to include in each category standards for which the requisite knowledge, understanding, and skills are similar. Marzano (2006) calls this “covariance,” which means that students would be likely to perform at a similar level on each standard included in what he calls “measurement topics””

- “Level 4: Advanced-A superior, consistent performance; beyond expected achievement Level 3: Proficient-A solid, consistent performance; demonstrated competency of knowledge and skills Level 2: Approaching-A partial mastery with limited to basic performance of expected achievement Level 1: Beginning-A limited mastery of knowledge and skills; below basic expectations”

- “These performance standards are criterion-referenced, not norm-referenced. This means that grades are determined by the actual level of achievement, not by the distribution of scores on a curve. In any one class, all students could demonstrate excellent achievement and receive As, or there may be no students excelling and achieving As.“

- “It is also important to remember that there is only one student’s name on the report card, so the evidence that goes into determining each student’s grade must be individual evidence. This means that if cooperative learning is used as a teaching strategy, individual assessment must occur after group activities have been completed. It is the individual evidence that is used to determine grades.”

- “Learning is a process, and students (and parents) must understand as they do in the arts and athletics-that there are different phases involved: a learning phase when students practice their knowledge, and a performance phase when students demonstrate what they know, understand, and can do. Teachers should provide feedback on formative assessments (those assessments for learning such as drafts, quizzes, and practice), but determine grades only from the evidence from varied summative assessments (assessments of learning). If we do this, we make grading supportive of learning.”

- “If a student shows today that she now knows, understands, or can do something that she did not know last week or last month, then the new evidence must replace-not just be added to the previous evidence. This is another way we make grading supportive of learning. This guideline means that students need to have several summative assessment opportunities to demonstrate what they know, understand, and can do in relation to each standard.”

- “This may happen as illustrated in the sample in Figure 2, but it also means that students should be given opportunities for second-chance or make-up assessments. It is of course important that students try hard and do the best they can on the first assessment; it is a waste of everyone’s time for students to have a second opportunity if they have not done anything to increase their likelihood of success. Therefore, students should provide evidence of “correctives” (such as peer coaching, tutoring, and additional practice) before they are granted a second opportunity. Second opportunities do not have to be convenient for students; there might be an “opportunity cost” attached (such as having the second opportunity occur outside class time) to help students recognize that it is better to put maximum effort into the first assessment.”

- “Instead of assigning a grade of zero, why not simply note that the evidence is missing with a blank space in the grade book? When it is time to determine a grade, decide if there is sufficient evidence to make a valid judgment. If there is sufficient evidence, determine the grade regardless of the missing evidence. (Concern about missing assignments or other evidence should be communicated prior to grading through phone calls home, email, and so on, and also on the narrative or expanded format section of the report card as suggested in Guideline 3.) If there is insufficient evidence to determine a grade, the student receives an I for “Incomplete” or “Insufficient” on his or her report card. This communicates accurately what the problem is and puts the responsibility where it should be-on the student. It gives students a second chance at success since arrangements can be made to complete the missing evidence”

- “Appropriate sampling: Quality assessment requires sufficient evidence to make good decisions, not too much or too little; measurement experts say that generally at least three pieces of evidence are needed, but the amount of evidence also depends on the consistency of the student’s performance. Consistent performance may require less evidence, while inconsistent performance requires more evidence.”

- “Change is always difficult, but if we recognize that how we grade makes a huge difference to students, it is obvious that we must ensure that grades are determined in ways that are logical and planned and that grades clearly communicate student achievement. “This requires nothing less than clear thinking, careful planning, excellent communication skills, and an overriding concern for the well being of students” (Guskey, 1996, p. 22).”

In any one class, all students could demonstrate excellent achievement and receive As, or there may be no students excelling and achieving As.

Ken O’Connor

Chapter 7: The Journey Toward Effective Assessment for English Language Learners (Lisa Almeida)

How can we effectively assess English language learners’ knowledge rather than their fluency in English?

Lisa Almeida

- “One crucial question looms large for classroom teachers of English language learners: How can we effectively assess English language learners’ knowledge rather than their fluency in English? Authentic or performance-based assessment instruments yield more accurate results with English language learners than traditional assessments, regardless of whether they are used to collect summative data (for a status report) or formative data (to affect learning). The results of these authentic assessments tend to be indicative of students’ conceptual understanding of a concept or skill. Effective measures of English language learners’ knowledge include performance assessments, cooperative learning opportunities, and the use of nonlinguistic representations (such as graphic organizers, dioramas, charts, and mental pictures), as well as teacher observations in conjunction with rubrics. Portfolios of learning are effective measures of students’ oral and written language skills (Díaz-Rico & Weed, 2006)”

- “Largescale standardized assessments (most often used as summative measurements) tend to provide invalid data, because they rely on students’ understanding of English at a certain level. More often than not, items on these assessments are selected response, extended multiple choice, and short constructed response. Without special accommodations-such as translations, a revised test format, or extra time-English language learners’ knowledge and skills will be adequately measured with these traditional assessments.”

- “Students engage in higher levels of thinking when complex performances are required; therefore, they gain an innate understanding of concepts and skills rather than merely a superficial understanding.”

- “Yet another significant advantage to using performance assessments is to provide students with opportunities to interact with one another.”

Chapter 8: Crossing the Canyon: Helping Students With Special Needs Achieve Proficiency (Linda A. Gregg)

- “The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) first asserted that students with disabilities must have access to the general education curriculum; No Child Left Behind (NCLB) went a step further, requiring educators to ensure that their specialneeds students not only have access to the general curriculum, but also achieve proficiency in it.”

- “To unwrap these standards, identify the nouns (content or concepts) by underlining them and the verbs (skills) by circling them … Then generate a list of the concepts and skills to be mastered from the standard. Some school districts unwrap the standards to make the information easily accessible to teachers. It is worthwhile to inquire if this information is already available at your school.”

- “For example, if the state or district format is multiple choice, it will be necessary to specifically teach students test-taking strategies to respond appropriately using this format. For students with special needs, low test scores can be a reflection of a change in test format.”

Chapter 9: Content Then Process: Teacher Learning Communities in the Service of Formative Assessment (Dylan Wiliam)

- “Raising achievement is important because it matters for individuals and society. If you achieve at a higher level, you live longer, are healthier, and earn more money. For those with only a high school diploma, the standard of living in the United States is lower today than it was in 1975; for those with degrees, it is 25 to 50% higher.”

- “The first generation of school effectiveness research just looked at outputs: Some schools achieved good results, and others achieved less good results. The rather simplistic conclusion drawn from this was that schools made a 185 difference, so the search commenced for features of effective schools (see, for example, Chubb & Moe, 1990). However, a second generation of school effectiveness research showed that demographic factors accounted for most of the differences between schools. Most of the schools getting good results were in affluent areas, and most of the schools with low student achievement were in areas of poverty. The conclusion based on this research was that maybe schools did not make so much of a difference, and the reasons for low student achievement were demographic (see, for example, Thrupp, 1999). More recently, a third generation of school effectiveness research has looked not only at the outputs of schools, but at the difference in what students knew when they started at the school compared to when they left-the so-called value added. What this research shows is that it does not matter very much which school students attend. What matters very much is which classrooms they are in in that school. If a student is in one of the most effective classrooms, he or she will learn in 6 months what those in an average classroom will take a year to learn. And if a student is in one of the least effective classrooms in that school, the same amount of learning will take 2 years. Students in the most effective classrooms learn at four times the speed of those in the least effective classrooms (Hanushek, 2004).”

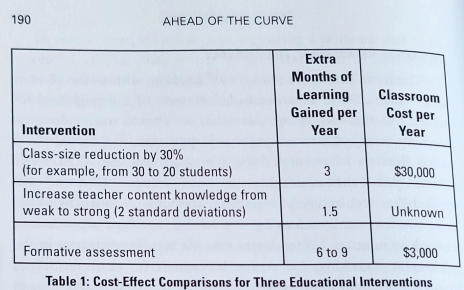

- “What accounts for these very different rates of learning? One obvious factor is class size, but it turns out that the effects of classsize reduction programs on student achievement are quite small, and such programs are very expensive (Hattie, 2005). Jepsen and Rivkin (2002) found that, for example, teaching 120 third-grade students in classes of 20 rather than 30 would result in just five additional students passing a standardized test, at a cost of around $120,000. In general, class-size reduction programs are most effective for younger students (kindergarten, first, and possibly second grade), and then only if class size is reduced to 13 to 15 students (Mosteller, 1995). For most students, the effect of class-size reduction is small.”

- “Over a year, the students taught by the most knowledgeable teachers (in other words, the top 5%) learned about 25% faster than the students taught by the least knowledgeable teachers (those in the bottom 5%). This difference was statistically significant, and bigger than the impact of socioeconomic factors, but nowhere near the 400% speed-of-learning differential between students in the most and least effective classrooms.”

- “While investment in teacher professional development has been a feature of the educational landscape for many years, there was depressingly little evidence that it made any difference to student achievement: “Nothing has promised so much and has been so frustratingly wasteful as the thousands of workshops and conferences that led to no significant change in practice when teachers returned to their classrooms” (Fullan, 1991, p. 315)”

- “For instance, a teacher might want to learn how to implement “jigsaw” groups, despite the absence of evidence that this is likely to make a difference to student achievement (indeed, according to Slavin, Hurley, & Chamberlain, 2003, not only is there an absence of evidence of an effect; there is, in fact, evidence of the absence of an effect). Similarly, there has been marked interest among educators in such strategies as “brainbased education” or learning styles despite the absence of evidence that these models make a difference to student achievement (see, respectively, Bruer, 1999; Adey, Fairbrother, & Wiliam, 1999).”

- “But note that the teacher learning communities are a means to an end, not an end in themselves: content, then process.”

- “The data in Table 1 suggest that investing in teacher professional development is 20 to 30 times more cost-effective than class-size reduction, at least beyond the second grade.”

- “If students have left the classroom before teachers have made adjustments to their teaching on the basis of what they have learned about the students’ achievement, then they are already playing catch-up. If teachers do not make adjustments before students come back the next day, it is probably too late. This is why the most important formative assessments are those that occur minute-by-minute and day-by-day (Leahy, Lyon, Thompson, & Wiliam, 2005).”

- “Formative assessment is: Students and teachers Using evidence of learning; To adapt teaching and learning; To meet immediate learning needs Minute-to-minute and day-by-day”

- “Clarifying learning intentions and sharing criteria for success 2. Engineering effective classroom discussions, questions, and learning tasks that elicit evidence of learning 3. Providing feedback that moves learners forward 4. Activating students as the owners of their own learning 5. Activating students as instructional resources for one another (A comprehensive review of the research underlying this analysis can be found in Wiliam, 2007.)”

- “For that reason, I draw a careful distinction between strategies and techniques. These five strategies are “no-brainers” they are always smart things to do in the classroom; however, the techniques used to implement these strategies require careful thought by the teacher. What might work for one class in one context might not be appropriate for another class regardless of how similar they appear to be. Through work with teachers and researchers in dozens of schools, my colleagues and I have developed a list of more than 100 of these techniques across the five strategies.”

- “Strategy 1: Clarifying Learning Intentions and Sharing Criteria for Success Technique: Sharing Exemplars 193 Before asking students to write a new kind of assignment such as a lab report, the teacher gives each student four sample lab reports that represent varying degrees of quality. These samples can be student work from earlier years-with the names removed, of course— or teacher-produced samples. Students are asked to place the pieces in order of quality and identify what is good about the good ones and what is missing or weak about those that are not as good.”

- “Using this kind of “all-student response system” helps the teacher to quickly get a sense of what students know or understand while requiring all students in the class to engage in the task. If all the answers are correct, the teacher moves on. If none of the answers are correct, the teacher may choose to reteach the concept in a different way. If there are a variety of answers, the teacher can then use the information gleaned from student responses to direct the subsequent discussion.”

- “Strategy 3: Providing Feedback That Moves Learners Forward Technique: Find It and Fix It Rather than checking all correct answers in an exercise and putting a check mark next to those that are incorrect, the teacher directs the student to identify them him or herself: “Five of these are incorrect; find them and fix them.” This kind of feedback requires the student to engage cognitively in responding to the feedback, rather that just reacting emotionally to his or her score or grade.”

- “At the beginning of the lesson, the yellow and red cups are nested inside the green cup. If a student thinks the teacher is going too fast, he or she shows the yellow cup, and if the student wants to ask the teacher a question, he or she shows the red cup. This teacher then introduced a new variation: As soon as one student shows a red cup, the teacher chooses at random from the students showing yellow and green, and the selected student has to answer the question posed by the student with the red cup. This modification by the teacher not only made the “traffic lights” more visible, but it also increased students’ accountability for their learning.”

- “In other words, rather than trying to transfer a researcher’s thinking straight to the teacher, this new approach to formative assessment emphasizes content, then process.”

- “In the same way that most of us learn what we know about parenting through being parented, teachers have internalized the “scripts” of school from when they themselves were students. Even the best 4year teacher education programs will find it hard to overcome the models of practice their future teachers learned in the 13 or 14 years they spent in school as students.”

- “Gradualism: Asking teachers to change what they do is rather like asking a golfer to change his swing in the middle of a tournament. Teachers who try to add more than two or three techniques to their teaching at the same time almost invariably find that their teaching routines fall apart, and they go back to doing what they know how to do. In the long-term, they achieve less change than teachers who take smaller steps.”

- “Second, the teacher learning community is genuinely a meeting of equals, at least in terms of power. In our experience, when one member of the community sets him- or herself up as the formative assessment “expert,” the learning of the other members is compromised.”

- “If we can concentrate on doing what is right, rather than what is expedient or easy, unprecedented increases in student achievement and teacher satisfaction are within our grasp. The question is whether we have the courage to reach.”

They encourage us to come to the plate because the team is losing to try to hit a home run. But we end up striking out instead. What the research shows us is that the only answer is continuous small improvements-“small ball,” if you like. We need to worry about getting to first base before we can make it home. We need to do this not because the solution is elegant or attractive, but because there is nothing else that we currently know of that works anything near as well.

Dylan William

Chapter 10: Data on Purpose: Due Diligence to Increase Student Achievement (Stephen White)

- “Data teams use the results from common formative assessments to create a framework for making instructional decisions at the classroom level, a first-order change (Besser et al., 2006). When the work of these data teams produces a collective sense of efficacy, and collaboration becomes part of a school’s culture, however, second-order change occurs (DuFour, Eaker, & DuFour, 2005; Hoy, Tarter, & Hoy, 2006; Murphy & Lick, 2004).”

- “The ability to disaggregate results by subgroup, content standard, and subscale over time provides rich insights into both learning and teaching.”

- “Learning data are most useful in determining how students respond to the curriculum, its pace, and its major areas of focus. They are less precise in identifying what instructional strategies are most effective simply because the assessments that produce these data do not monitor teaching. Learning data are by definition data collected “after the fact,” and changes we implement as a result of analyzing learning data are responsive rather than proactive. Formative, short-cycle assessments are designed specifically for the purpose of early, responsive adjustments to instruction, but to be proactive requires data about teaching and about learning.”

- “Teaching data help educators make informed inferences as to why there is variability across content standards and among student subgroups, but conclusions and decisions will be based on effects, not causes. Whereas learning data clearly identify differences in performance, teaching data explain these differences with greater clarity in terms of teachers’ actions and choices.”

- “Triangulation is a means of determining precise targets with limited information-a way to gain meaning from raw data, find critical information, see the big picture, and identify key interactions among variables.”

- “Because teaching and learning are so complex, it is important to remember that educational cause-and-effect relationships are not laws of physics, and correlation is not causality.”

Because the single most powerful influence on student achievement is the teacher (Wenglinsky, 2002), every teacher interaction with students and with other teachers qualifies as potential data on teaching.

Stephen White

- “Many powerful programs are sound in their pedagogy, but efforts to replicate them are often ineffective because they are not implemented as designed, monitored as created, or followed with fidelity over time (Elmore, 2004; Sparks, 2004; Steiner, 2000). Instructional strategies are measured by learning and teaching data. Important aspects to measure include type of strategy employed, degree to which protocols are implemented, and evidence of success in student work.”

- “Collaborative peer observations promote improved teaching practice (Buchanan & Khamis, 1999), and sustained longitudinal gains in achievement occur when collaborative structures are present and encouraged (Kannapel, Clements, Taylor, & Hibpschman, 2005; Langer, Colton, & Goff, 2003).”

- “Yet sometimes an excellent strategy with collective backing can still yield lackluster results; in such cases the problem may be lack of accountability. Accountability is the sum of followthrough, feedback, rewards, transparency, and even sanctions.”

- “The evidence discussed in this chapter is all generated internally within schools, grade levels, and departments. Our work will be most successful when we base it on evidence from our experience rather than on another’s research or reference. Meaningful data on learning, teaching, and leadership are waiting to be captured and analyzed in every district, school, and classroom-by those who approach data with a sense of purpose. We need only add our professional judgment and collective wisdom to bring forth the insights on best practices that our students need to achieve at high levels. Using data on purpose brings us closer to developing a standard for due diligence in education, a standard by which we will seek out the most relevant data and analyze them in the context of proven best practice before discarding effective approaches or adopting ineffective ones. By pursuing data on purpose, educators can turn data analysis into a process of discovery-a treasure hunt for insight.”

Chapter 11: Challenges and Choices: The Role of Educational Leaders in Effective Assessment (Douglas Reeves)

Watch any child play an electronic game, where the supply of accurate, timely, and specific feedback seems endless: He sits, transfixed and immobile, for hours at a time as the steady stream of feedback lures him, in the parlance of the gamer, to “get to the next level.” This same student is inattentive and disengaged in class.

Douglas Reeves

- “Equipped with these evidence-based conclusions, the question we must address as educational leaders is not, “What shall we do to improve student achievement?” This is already clear. Rather, we must focus on the remaining question: “How do we implement and sustain practices and policies that support improved student achievement?”

- “While we know that immediate feedback is essential for improvement, schools continue to maintain the practice of “final” exams, with the implicit message that feedback from the teacher in this context is irrelevant and futile.”

- “Perfection is not an option, and leaders who delay the pursuit of progress as they pursue perfection in assessment policies will doom themselves and their school to what Tom Peters and Robert Waterman (1982) decried as analysis paralysis. Change is delayed as perfection remains the enemy of progress, while toxic and ineffective practices remain entrenched.”

- “To test whether the standards-time mismatch affects the assessment agenda in your school, simply ask a group of teachers to fill in the blank in the following sentence: “We would like to do a better job on assessment and feedback, but we just don’t have the __ “It is unlikely that they will suggest “intellect” or “ability” or “desire”-or even “money.” By far the most common reason classroom teachers do not have more frequent and effective assessments is that they lack the time to cover the curriculum, develop assessments that match the curriculum, and provide feedback that is detailed and specific.”

- “To identify power standards, the faculty must address three questions: First, which standards have endurance? That is, which standards appear to be of lasting value from one grade level to the next? Reading comprehension is obviously included in this criteria, while just about anything involving plastic volcanoes is not. Second, which standards provide leverage? That is, which standards have applicability in multiple disciplines? Nonfiction writing and the ability to create and draw inferences from graphs and charts clearly have multidisciplinary leverage, while the ability to distinguish the trapezoid from the rhombus is of more limited utility. Third, which standards are most essential for the next level of instruction? The answer to this question is tricky, because if I ask a group of fourth-grade teachers, “What are you willing to give up?” the typical response is, “Nothing. Everything we do is important, and besides, the kids need it for next year.” But when I walk down the hall and ask a group of fifth-grade teachers what I would need to do as a fourth-grade teacher so that my students could enter fifth grade with confidence and success, the answer is almost always a very brief set of requirements. … In other words, we must be able to distinguish what teachers love from what students need.”

- “Indeed, I have seen some classroom assessments that were designed to provide timely and effective feedback for students and teachers, but because the assessments required 2 hours to administer and a week to evaluate, they became a waste of time.”

- “Why were the assessments so long? Certainly there was no malicious intent to waste teachers’ and students’ time. Rather, the teachers and administrators constructing the assessments recalled their college assessment classes in which they were admonished to construct tests with adequate domain sampling (Crocker & Algina, 1986) and a sufficient number of items so as to achieve a high degree of reliability.

- The problem is that these standards for test construction apply to high-stakes norm-referenced tests designed to carefully separate the performance of one student from another. If our purpose is the selection of students for a limited number of places in next fall’s Yale Law School class, then a focus on extensive domain sampling and high reliability would be appropriate.”

- “This is a fair challenge, and the answer is not that a 10-item test designed by teachers, with results returned in hours rather than weeks, is superior to a 100-item test designed by professional test writers. The answer, rather, is that school leaders must choose which error has the least risk for their students.”

- “One thing that high-performing schools uniformly do is establish literacy as their primary pursuit (Reeves, 2004a, 2004b).”

- “Consider the evidence on the relationship between time and student literacy. In what some readers may regard as a “blinding flash of the obvious,” we have observed that elementary schools that devote more time to literacy experience higher levels of student achievement. Specifically, in one school system we studied, we found that in schools that devoted an average of 90 minutes per day to literacy instruction, 55% of the students scored at the proficient level or higher on state tests of reading comprehension in schools averaging 120 minutes of daily instruction, and 72% of the students scored at the proficient level or higher; in schools averaging 180 minutes per day of instruction, more than 80% of the students scored at the proficient level or higher. Of particular interest is the fact that the last group of schools began the year with the lowest performing students.”

- “While it is easy to offer the rejoinder that time alone is not enough, and how one uses time is important, such a discussion is beside the point if we do not first give teachers the time that they need to help students catch up to where they need to be and also receive grade level instruction.”

- “It is important to note that the mantra of “reading across the curriculum” is not a sufficient replacement for direct instruction in reading and writing. I challenge you to look at a dozen randomly selected samples of student writing at any grade level in your system, and then make the claim that students will be harmed by additional explicit instruction in reading and writing.”

- “It is only a matter of tradition that meetings are reserved for announcements. Leaders in collaborative cultures dispense with the formalities and invest time in genuine collaboration.”

- “How much time does effective collaboration take? First, we must be absolutely clear about what “collaboration” means in the context of creating and implementing effective assessments. At the very least, teachers must create common assessments (Ainsworth & Viegut, 2006; Reeves, 2002); examine the results of those assessments to improve teaching practices (White, 2005a, 2005b); and examine student work (Reeves, 2004a).”

- “Consider the evidence on how 50 educators examined anonymous samples of student work and, using the same scoring rubric, came to strikingly different conclusions. In the course of six 4hour meetings a total of 24 hours-the same group’s level of agreement rose from 19% to 92% (Reeves, 2006b). While it is easy to say that collaboration is essential for fair assessment, and that effective collaboration requires time and practice, consider how the last 24 hours of faculty meeting time were spent in your school.”

If these findings are so obvious, why do schools so rarely give priority to literacy? Why is the prevailing model in school schedules the presumption that all subjects are of equal value and thus deserve equal time?

Douglass Reeves

Epilogue: Once Upon a Time: A Tale of Excellence in Assessment (Richard DuFour)

- “Good stories teach us. They convey not only how something should be done, but more importantly, why it should be done. They communicate priorities and clarify what is significant, valued, and appreciated.”

- “Peter was asked to review the “Essential Learnings” established by the U.S. history team and was struck by the fact that the curriculum stressed only 10 key concepts each semester, rather than the long list of discrete facts he had been expected to teach at his former school. The selection committee also gave Peter copies of the curriculum pacing guide, the common assessment calendar, examples of preassessments for several units, examples of common assessments, and the rubrics for evaluating student essays and term papers-all of which had been created by the U.S. history team. The committee asked Peter to critique each document and to express his concerns as well as suggestions for improvement”

- “The team also reviewed an analysis of the very strong correlation between results on their common assessments with the results of the high-stakes state and national exams. “We know we are on the right track,” Ambrose, the team leader, observed. “If we can help every student be successful on our ongoing common assessments, we can be very confident they will be successful on state and national assessments as well. We can continue to assess students in other concepts we deem important, but we have an obligation to help our students be successful on the high-stakes tests they must take.””

- “We are always looking to get better, and even on a test where students well, there’s always a concept or a few items where they do least well. If our team can identify effective strategies for addressing those areas, we can become even more effective and help more students achieve at higher levels every year.””

- “Miriam explained to Peter that at the start of every unit, teachers administered a brief preassessment of those terms to their students. Because there were at least two sections of history taught each hour, and because the history classrooms were next to one another, teachers were able to divide students into two different groups based on their proficiency with the vocabulary.”

- “Peter’s team continued to meet for 1 hour each week. On Monday mornings, teachers reported to work 15 minutes earlier than usual, and the start of classes was delayed 30 minutes in order to create this collaborative time. Teachers were then allowed to leave 15 minutes earlier than usual on Mondays, so they were not required to work longer hours or to sacrifice personal time in order to collaborate with their colleagues.”

- “We’re willing to accept a difference of one point on the fivepoint scale,” Ambrose explained, “but if two members present scores with a variance of more than one point, we’ll discuss the variance, review our rubric and the anchor essays, and then determine an appropriate score.” Peter was somewhat chagrined when he was the only team member whose score deviated from the rest of the team the first two times they practiced applying the rubric. His colleagues, however, were very supportive. They explained the thought process they used in scoring the sample and encouraged him to articulate his reasoning. The dialogue was helpful, and on the third attempt to review a sample essay, his score was consistent with his colleagues.”

- “He directed questions to students randomly, rather than relying primarily upon volunteers. He extended wait time whenever students struggled and refused to let any student simply declare he or she did not know the answer. He would prod, rephrase, ask them to explain their thought process, and insist they clarify exactly what they did understand and exactly where they were confused. Students soon learned that a simple shrug would not suffice for Mr. Miller. They also learned that he rarely affirmed or corrected an answer immediately. Instead, he would provide more wait time and then direct a student’s response to several other students for analysis and comment. He encouraged debate and insisted that students explain their thought process.”

- “At the end of today’s class, I will be able to…”

- “The first showed how his students had performed on each skill and concept the team had assessed, compared to the performance of all the students who completed the assessment. The second printout presented an item analysis that compared the results of his students to all students on each item on the assessment.”

- “My students obviously didn’t get the concept of republicanism,” Miriam said. “How did the rest of you teach that?” Various team members shared their strategies, then brought up the weak spots in their own students’ performance.”

- “”Why, we’ll celebrate our success, of course,” she said. “And then we’ll look for the next items where students did less well. There will always be ‘the lowest 10 percent of items on any assessment we give. We attack those items, implement improvement strategies, celebrate our success, and then look for the next items. That is the beauty of continuous improvement. You never really arrive, but there is always a lot to celebrate.””

- “”I don’t understand the rationale behind this process,” Peter said. “Why not grade the first essay and average the scores?” “Well,” Frank said, “we just don’t think it’s reasonable to assign a grade to skills students are attempting to use for the first time. We and want our kids to have the benefit of specific feedback before we redos grade their efforts.” “We think giving feedback tells students that we expect them to achieve a standard,” Miriam chimed in, “and that we’ll ask them to refine and improve their work until they reach it. Later in the year, they won’t have this chance, but for now, early in the learning process, we feel it’s imperative that students benefit from practice and specific feedback before we assign grades to their work.””

- “Burnette High had created a schedule that ensured each student had one period available each day to receive this additional time and support for learning. Upperclassmen who did not require this intervention were given the privilege of unstructured time, while freshmen and sophomores were assigned to study halls.”

- “Two weeks later, the students who had completed this first intervention were given another opportunity to demonstrate they had learned the key concepts of the previous unit by taking another form of the assessment. If they performed well, their failing grade was dropped and replaced with the higher grade for students. Miriam explained, “We say we want them all to learn; we don’t say that we want them all to learn fast or the first time. If some students have to work harder and take longer before they demonstrate proficiency, so be it. In the final analysis, if they demonstrate proficiency, we give them a grade that reflects that.””

- “Peter was still a little skeptical. He thought that an opportunity to take a second assessment would cause students to “blow off” the first test. Afterwards, however, he had to admit that he was wrong. His juniors truly valued their unstructured time. They knew that poor performance on the first assessment would mean not only the loss of that privilege, but also an extra commitment of time and effort to learning what they should have learned in the first place. Peter could see no evidence that students were indifferent to the results of their first test.”

- “If all the teachers of a course were expected to teach the same concept, it was certainly more efficient to work collaboratively in planning the unit, gathering materials, and developing assessments than to work in isolation and duplicate each other’s efforts.”

To limit the use of this powerful instrument to ranking, sorting, and selecting students is analogous to using a computer as paperweight. When done well, however, assessment can help build a collaborative culture, monitor the learning of each student on a timely basis, provide information essential to an effective system of academic intervention, inform the practice of individual teachers and teams, provide feedback to students on their progress in meeting standards, motivate students by demonstrating next steps in their learning, fuel continuous improvement processes—and serve as the driving engine for transforming a school.

Richard Dufour

Read This Next

- How To Think About Teaching

- How To Teach

- ResearchED Toronto Takeaways 2024

- Chalk & Talk Podcast Notes – Anna Stokke

- The Life of a High School Teacher

- The Biometrics of High School Teaching

- Takeaways From Teaching High School Math For 2 Months

- Deep Work – Book Notes

- The Tutor & The Gardener – My Teaching Philosophy

- Atomic Habits – Book Notes

- Productivity for Students

- How I Would Study for the Math Proficiency Test

- Millionaire Teacher – Book Notes

Resources

- Ahead of the Curve

- Growin Success

- Drive — Daniel H. Pink