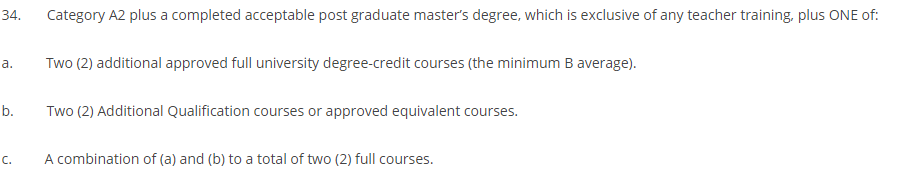

I wrote a letter to myself in 2018. The purpose of this letter was to lay out my internal conflict of whether or not I should pursue a master’s degree or start teaching. Contributing to society was always a core value of mine. Work is often valued over education in my family and hometown. I wasn’t sure if I was just delaying responsibility (Peter Pan syndrome) or if my drive for higher education was justified. Teachers in Ontario are paid based on their previous education and the extra courses they take after completed their B.Ed. I completed a 3-year undergraduate degree in mathematics before heading to teacher’s college. As a result, I got assigned the A2 salary level where A4 is the highest. I could expect to get paid about 53K in my first year of teaching while someone with A4 can expect to get paid approximately 58K. After 10 years of experience, the gap expands to 86K versus 100K. Most teachers start at A3 (four-year degree) and take additional courses through the faculty of education to move up to A4. According to line 34 of QECO’s General Education Chart, a master’s degree with two additional courses should get me from A2 to A4.

I do not want to be a student forever. However, I needed to do a significant amount of extra courses to move up the salary grid that it started to make sense to attend graduate school. I was torn between the two options. I am writing this letter in hindsight to remind myself of how bad we are at making informed decisions. There are almost always more than two options. Below are factors I did not even consider when making the decision and a few fears that I had.

I would never do a master’s in math or stats.

At the time (previous article), I wanted to do a master’s in psychology. Yet, here I am a few years later almost done with my master’s in statistics.

I went to Carleton University to meet with the psychology and neuroscience advisors to discuss the possibility of joining their graduate programs. I was basically told that I would need to complete an undergraduate degree in their field to be admitted. This was discouraging. I really did not want to take courses from the faculty of education. I dropped by my math undergraduate advisor’s office to chat since I was already at Carleton. It was he who mentioned the possibility of doing a master’s in statistics. It was past the admissions deadline but he told me to apply despite having a three-year mathematics degree with a few stats courses. I signed my letter of admission that same afternoon. Just like that.

We often get caught debating the wrong things. I was on the fence between working as a teacher or doing a master’s in psychology. Sometimes it takes a black swan (affiliate link) to shift our paradigm.

Covid is not going to affect us.

Speaking of black swans. I am sure I am not the only one who did not consider the potentiality of a global pandemic when choosing whether or not to attend grad school. In hindsight, I think attending online lectures was an easier transition than it would have been if I was teaching. Many of my friends who taught during the pandemic said it was a nightmare. Conversely, grad courses are well suited for the digital world since most of the work is independent and done outside of lectures. Each of my grad courses consisted of approximately three hours of lectures and 15 hours of work per week. It is weird to say but I preferred the online format for lectures for a few reasons. First, I did not have to commute to school. Second, I could eat, stand, and stretch during lectures. Third, the lectures were recorded and notes often posted. The pandemic did have significant side effects on many other aspects of my experience. It was impossible to do the mental calculus when it came to covid.

I am going to be in so much debt.

Another limiting belief of mine was going to fall behind my peers financially. We all have a story of what we should be doing with our lives by a certain age. My story was that I was going to start working after university. My goal was to break even financially during my two years at Carleton. The funny thing is that I made money. I did not consider potential scholarships which reduce the cost of tuition. I failed to consider that graduate teacher’s assistants get paid very well. I did not take into account that I could have meaningful summer jobs that pay well. I did not realize how much the lockdowns would cut down expenses while leaving my income streams intact. Lastly, I failed to recognize that by doing a co-op, you are essentially paid to go to school and build your resume. The only downside is that you may take longer to complete your degree. Of course, my experience won’t translate to everyone else’s or even my own in different circumstances. The point is that our emotions often drive our behaviour. Writing things down and using other people as sounding boards are the best tools we have to clarify our thoughts. Even when done successfully, we make decisions based on incomplete information in an attempt to please our future self who is a stranger to us (read Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert for more on this).

Dropping courses is for losers.

The typical length of my program is two years (8 courses with 2/semester). Two years have passed since the start of my master’s and I still have to complete two more courses. I dropped a course in the second semester of my first year. This was a hard decision for me because I had a belief that quitting is a bad thing.

Quitting, for me, means not giving up, but moving on; changing direction not because something doesn’t agree with you, but because you don’t agree with something. It’s not a complaint, in other words, but a positive choice, and not a stop in one’s journey, but a step in a better direction. Quitting-whether a job or a habit-means taking a turn so as to be sure you’re still moving in the direction of your dreams.

Pico Ilyer

I had three goals going into my master’s degree.

- Graduate.

- This would allow me to move up the teacher salary grid.

- Learn statistics and experimental design.

- I want to answer everyday questions based on data (see Daylio article).

- Learn to code.

- Programming was another limiting belief of mine.

- Being able to code opens so many doors.

- It will make me a better teacher.

I am glad to say that all three of these goals were attained. I was struggling in my first-year courses. My background was in mathematics and not statistics. The course I dropped in the second semester was beyond my learning capabilities at the time. I am confident that I could have passed the class but that was not the point of going back to school. I could not devote as much time to the other course I was taking which contributed more to my learning goals. In hindsight, I could have stayed in the course. Still, there is no way of knowing what the “right” course of action was. That is the whole point of this article. There are only different consequences.

I never considered that it might take me more than two years to complete the program. Adding an extra year to the mix influences drastically the mental calculus used to make the decision. The story that I had to finish the program in two years had to go. The more stories we let go of, the more at peace we tend to become.

No one will hire me as a teacher because I did not start right away.

I have yet to disprove this belief since I have not yet applied for teaching positions. However, I am confident that having a master’s degree is an asset to my resume. I was able to gain additional teaching experience. I was a TA for two courses every semester. I created math explainer videos for Carleton as a summer job. I tutored a few clients throughout the degree. My analytics co-op with the Ravens women’s basketball team taught me many valuable communication skills. Last but not least, I created Duddhawork during my master’s. I am not sure I would not have had the time and energy to do so if I started teaching. The first years of teaching are extremely demanding. Again, this fear was not founded entirely on facts but more on stories of falling behind a fictional standard narrative.

I can’t do research.

I was terrified by the thought of doing research. For this reason, I opted for the course-based program so I do not have to write a thesis. Something has changed. I have considered doing research for the first time. The analytics co-op position made me realize that research, for me at least, is more about picking an interesting problem. In that sense, I do research all the time. It is the rigorous aspect of research that deters me. I get excited about solving the problems and communicating the results to my friends. Writing a formal report that no one will read does not jive with that notion. I also realized that I am an ideas person. I get more excited in the planning stage than in the implementation. Studying a narrow topic for years might not be best suited for my personality. And that is ok with me. There is still a significant chance that I do research eventually. It is by getting to know ourselves that we can shed the stories that bind us.

Takeaways

The juxtaposition of this article and the previous one reveals some interesting insights about our attempts to make good decisions.

- We make decisions based on incomplete information.

- We do not take into account the black swans.

- We project our current goals and values and assume that our future selves will be similar.

- We often fail to realize the false dichotomy when choosing between “two” options.

- We assume that there is only one good life. Any deviation from this narrative will leave us suboptimal.

- We all carry stories of what we should do with our lives.

- We will always find ways to justify our behaviour in hindsight to limit cognitive dissonance.

All of this is not to say that trying to make decisions to improve your life is futile. Understanding our biases is necessary but not sufficient. We can all come to terms with the fact that our decisions are flawed and that there is rarely one option that is completely superior to the others. That way, we can spend less time on small decisions and more time on big decisions. Self-correcting is more important than making the “right” calls in the first place.

Affiliate Links

- Black Swan – By Nassim Taleb

- Stumbling on Happiness – By Daniel Gilbert