This is the second article of a two-part series. In this first article, we’ve weaved a conceptual framework for how to think about teaching. We’ve identified and clarified the objective of teachers and painted some broad strokes principles (strategy) for how to evaluate the efficacy of specific pedagogical practices (tactics). The purpose of having a clear objective and a deep strategy is that it allows one to select and rank tactics by asking the following questions:

- Does this tactic move me closer to my objective?

- How well does this tactic align with my overall strategy?

The article below is lengthy with much specific advice, so I recommend implementing one tactic at a time and thinking critically about how it fits into your overall strategy. It’s easy to get lost in the swamp of tactics.

The following is a list of experience and evidence-informed practices I implemented in my high school math and physics classroom.

Assessment

Backward Design

Recall that our objective is to bring as many students as possible to a mastery level (>= 85%) on the curriculum‘s overall and specific expectations (standards). Hence, for our assessments to be valid, they must test the curriculum’s expectations. The easiest way to ensure this is done is to start by writing the final exam and summative tasks in a way that would provide evidence of mastery of the curriculum standards. Once the assessments are built, the instruction sequence can be planned to prepare students to perform well on these tests. This practice is referred to as backward design.

Standards-Based Grading (SBG)

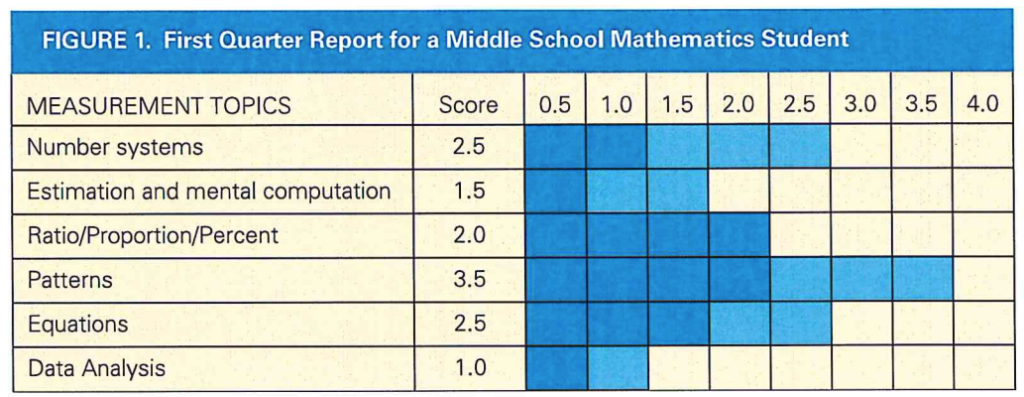

A natural extension of backward design is a reporting method called standards-based grading (SBG). Instead of getting a B or 14/20 on the unit 2 test, students receive a grade for each of the curriculum’s overall expectations. As a result, the grades are more informative and actionable. They allow the students, parents, and teachers to target the areas where more practice is needed.

Another benefit of SBG is that growth mindset, mastery learning, and spiralling are built into the system. As seen in the picture above, there’s a grade for each standard. The student can immediately see that they might want to review the Data Analysis content and do more practice problems while they don’t need to spend as much time on Patterns. The darker blue represents their initial performance, and the lighter blue illustrates their final performance. The students can see the progress which increases intrinsic motivation (see Daniel Pink’s work).

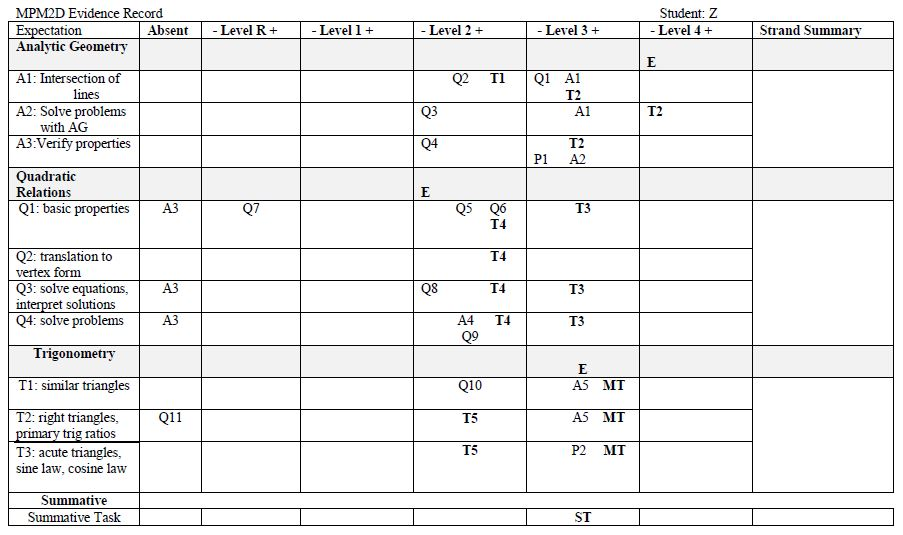

The specifics of SBG will vary depending on the school board, but anchoring assessments to mastery of the curriculum standards should remain stable. Marzano uses these tables to convert proficiency scores to letter grades and percentages. The Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB) organizes their evidence record as seen in the picture below. Their full process is laid out in this series of articles.

SBG aligns with the Growing Success philosophy stating that:

The report card grade represents a student’s achievement of overall curriculum expectations, as demonstrated to that point in time. Determining a report card grade will involve teachers’ professional judgement and interpretation of evidence and should reflect the student’s most consistent level of achievement, with special consideration given to more recent evidence.

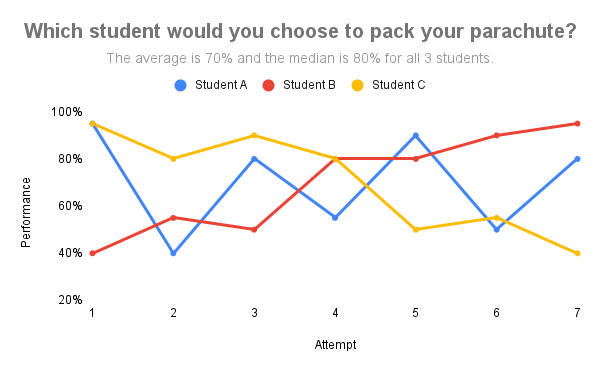

Consider the example below from Ken O’Connor’s lecture to drive home the point. Which student would you choose to pack your parachute by the end of the seven attempts?

It’s crucial to keep our objective in mind when evaluating the relevance of a particular tactic. Our goal is to assess and facilitate mastery of curriculum standards. A missing grade or a case of plagiarism is not evidence of a lack of mastery. Instead, it reflects on poor learning skills and work habits and hence, should not impact the grade. All we can conclude is that there is “insufficient evidence” to provide a grade (see fix 12 below). A student who handed in everything and finished the course with a 60% is categorically different than a student with 90s in everything except the one project which was submitted late and ended up with a 60%. If grades are to be a valid measure of a student’s achievement on the standards, then zeros should not be factored in the grade and an “I” for “insufficient evidence” should be reported. I like O’Connor’s line of reasoning on how to deal with missing work or plagiarism. He suggests behavioral consequences for plagiarism (see fix 4 below) and that we ask ourselves the following question:

Do I have enough evidence to make a valid and reliable judgment of the student’s achievement?

If the answer is yes, the grade should be determined without the missing piece. If the answer is no, then the grade should be recorded as “I” for “Incomplete” or “Insufficient evidence.” This symbol communicates accurately that, while the student’s grade could be anywhere from an A to an F, at the point in time when the grade had to be determined, there was insufficient evidence to make an accurate judgment.

.

Personally, I believe a student should not be able to pass the course with missing grades unless there are extreme circumstances and the teacher has “enough evidence to make a valid and reliable judgment of the student’s achievement”. Late submissions and plagiarism are examples of behavioral issues and should strictly be reported on via learning skills and work habits. Making the students redo the project after school appears to be a more logical consequence given our objective than handing out zeros.

Below are O’Connor’s 15 Fixes for Broken Grades:

- Include only achievement; don’t include student behaviors in grades.

- Support learners so they meet timelines; don’t reduce marks on late assessments.

- Use only evidence of achievement; don’t provide extra credit or use bonus points.

- Apply behavioral consequences and reassess when academic dishonesty occurs; don’t reduce marks.

- Report absences separately; don’t consider attendance in grade determination.

- Use individual achievement evidence; don’t include group scores in grades.

- Organize and report evidence by standards/learning goals or targets; don’t organize by assessment methods or report a single subject grade.

- Provide clear descriptions of proficiency levels; don’t assign grades using inappropriate or unclear performance standards.

- Compare each student’s performance to preset standards; don’t assign grades based on student comparison.

- Use evidence from high quality assessments; don’t use evidence from low quality assessments.

- Consider several measures of central tendency and use professional judgement; don’t rely on the mean.

- Use Incomplete or Insufficient Evidence and provide support when evidence is missing; don’t include zeros in grade determination.

- Use evidence primarily from evaluative assessments to determine grades; don’t use evidence from formative assessments.

- Emphasize more recent achievement; don’t just summarize evidence accumulated over time.

- Involve students; don’t leave students out of the grading process.

I recommend reading Thomas M. Haladyna’s paper assigning a valid and reliable grade in a course. It emphasizes the need for more objective assessments methods as suggested in O’Connor’s tenth fix. Haladyna is a fan of developing quality multiple-choice items. However he warns us that “some instructors tend to avoid performance tasks as a basis for grading and resort to multiple choice to measure knowledge and skills. This may misrepresent the important learning outcomes that they desire. For instance, would a multiple-choice test suffice for driver licensing?” Additionally, Haladyna provides the following principles:

- Domains, the subject matter, have been identified and shared with students.

- Instruction provides opportunities to acquire knowledge and skills from these domains and apply each in complex ways to tasks.

- The grading criteria represent a reasonable and fair sample of each domain.

- Grading principles are identified and shared with students.

- Grading standards are fair and publicly revealed on or before the first day of class.

- The weighting from knowledge, skills, and abilities should be public (i.e., in the syllabus) and well known to students.

- To maximize reliability, it is therefore useful to have as many sources of information about student achievement in the course as possible. A good example is the use of many grading criteria, such as quizzes, tests, projects, and class-participation activities. Moreover, the multiple indicators cover the content more comprehensively, which improves validity. In other words, more grading criteria not only increases reliability but increases validity.

- Grades should be objectively determined, because subjective judgment has many shortcomings, as reported in many essays and books (Meehl, 1954; Egisdottir et al., 2006). However, sometimes, subjective judgment is the best an instructor can offer. In those instances, students should have the opportunity or the right to appeal. Granted, objective determination of a grade ultimately depends on a subjectively determined set of grading standards, but such subjectivity is unavoidable. The argument defending the subjective establishment of grading standards is that an instructor’s expertise and experience weighs in favor of setting fair and defensible standards.

- Instructors want their students to earn high grades. High grades ideally reflect high achievement and effective learning and teaching. Of course, low standards can also yield high grades, but that situation should be avoided.

- The goal for any instructor is to skew the distribution more negatively, because that is what teaching and learning is all about.

- In a professional program, mastery makes much sense. Who wants their daughter’s brain tumor removed by a C student in surgery? Mastery may thus be an ideal method for teaching, learning, and grading, but its primary obstacle is feasibility.

- A dilemma is whether a student who takes more time to learn should earn a lower grade?1

- If you as an instructor base student grades on your criteria and standards, and students achieve highly, they deserve the grade they earned.

- If you allow lowachieving students more time to learn, they will likely learn more and both earn and deserve a higher grade. This may seem like grade inflation, but the goal of teaching is to increase learning. Allowing more time to learn thus improves achievement for low-achieving students

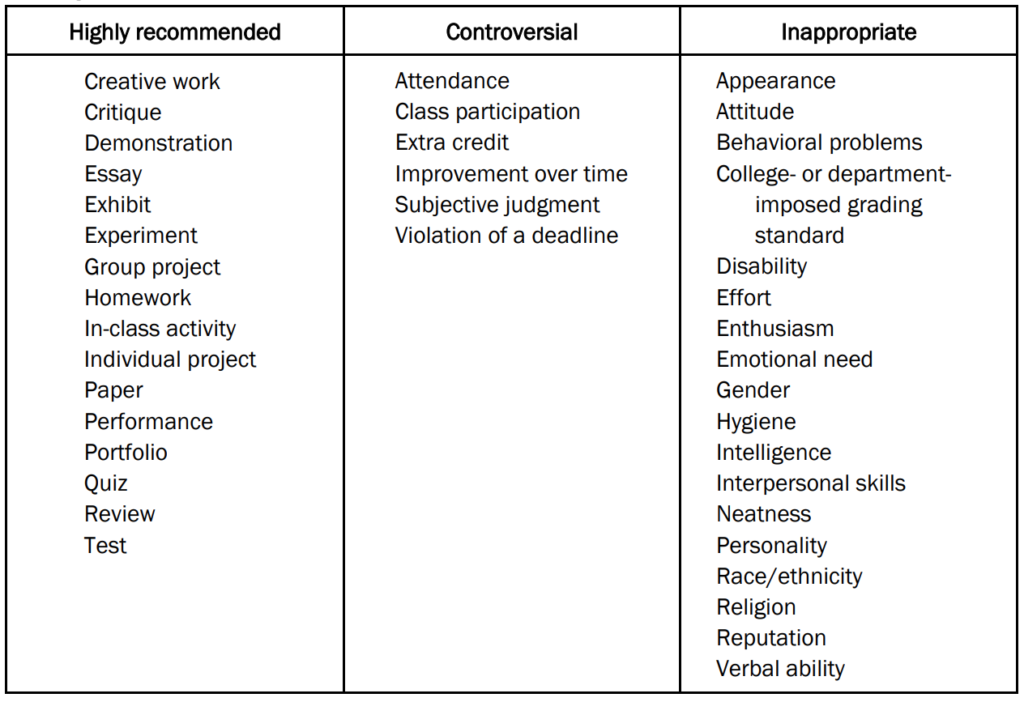

- Consult the table below for recommended grading criteria:

Personal tips and tricks:

- Prepare the answer key before printing copies for the entire class. This has a few benefits:

- You’ll often find typos or small clarifications you can fix before printing.

- You can assess if the length and difficulty of the assessment is appropriate.

- Your answer key and marking scheme are established in advance. This circumvents the possibility of basing the grading scheme on students’ performance.

- You can communicate the importance or weight of each question to students.

- Accumulate a series of micro-judgements on each question by assigning points to each question. Combine the points into an overall score for each standard. Ask yourself if the scores map onto the proficiency scale with letter grades. If not, you may want to use professional judgment to adjust the final grade or change the distribution of points.

- It’s best to go from a percentage to a letter grade because percentages give the illusion of precision and reduce reliability. It’s unlikely that a teacher grades the same test a week later and ends up with the same percentage. However, the teacher is more likely to converge on the same letter grade because it represents a range of percentages and maps to a qualitative proficiency scale.

- Grade one question or one page at a time. It increases reliability. It’s rare for a teacher to grade all the tests in one sitting. Due to several biases, it’s effectively another grader from sitting to sitting. By marking one question at a time, you distribute your biases equally across the class. By marking over several sittings, you benefit from being fresh and having multiple perspectives. It’s essentially a team of people marking the test and the members of this team are different versions of you.

- Annotate the grading scheme with how you distributed points for common mistakes.

- Take note of common mistakes to address them once everyone has written the test. You may need to adjust your teaching for the next time you teach the course.

- Don’t provide extensive feedback on summative assessments. It’s extremely time-consuming. You want to let students try to correct their mistakes. I encourage my students to ask for clarifications when they’re unclear as to why they lost points. This rarely happens even though I don’t provide detailed comments. The purpose of summative assessment is to measure learning and is typically done at the end of the study period. Extensive feedback is more pertinent before the summative assessment.

- Grading is fundamentally subjective. Thus, I encourage my students to contest their grades if they are confident that my judgment was off. This is a terrific way to involve students in the grading process (see fix 15).

- Hide the names of students when possible. A practical way to do this is to make students print their names on the last page of the test. You can also write the grades on the last page, which is better for privacy when distributing the test. It has the additional benefit of encouraging students to review their mistakes before getting to the grade.

- Shuffle copies after grading each page or question to remove any ordering bias.

- Evaluate strictly based on the grading scheme. Do not remove points for handwriting and other extraneous factors.

- Don’t be shy to ask your colleagues to validate your subjective judgments. Peer and self-assessments may help you validate your judgment as well.

- When in doubt, give the benefit of the doubt to the student.

- Circulate before the test or in the first few minutes to prevent cheating. Only allow the students to have the test and writing instruments on their desks. Everything else must be on the floor or in their locker. Don’t allow any electronic devices.

- Display the time with the projector. I do this using classroom screen. My students say that having access to the precise time reduces their stress.

- Design your assessments to limit ambiguity. If many students ask for the same clarification, this is an indication that you need to reformulate the question.

- Design your questions in a way that students are forced to answer everything with empty space to be filled.

Instruction

Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction

Barak Rosenshine’s principles of instruction below present 17 evidence-informed tactics that fit well in our overall strategy and are associated with increased learning. These principles are common-sensical and align with many of the core findings of cognitive science and other fields.

- Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning.

- Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step.

- Limit the amount of material students receive at one time.

- Give clear and detailed instructions and explanations.

- Ask a large number of questions and check for understanding.

- Provide a high level of active practice for all students.

- Guide students as they begin to practice.

- Think aloud and model steps.

- Provide models of worked-out problems.

- Ask students to explain what they have learned.

- Check the responses of all students.

- Provide systematic feedback and corrections.

- Use more time to provide explanations.

- Provide many examples.

- Reteach material when necessary.

- Prepare students for independent practice.

- Monitor students when they begin independent practice.

Explicit Instruction

Explicit instruction (EI) or direct instruction (DI) is what people typically mean when they think about teaching. I strive to implement Zach Groshell’s version of direct instruction in my classroom. I recommend listening to the 4-minute audio snip from episode 10 of the Chalk & Talk podcast.

Katherine Beals and many others argue that direct instruction (I do, We do, You do) should be the leading candidate for universal design.

Explicit teaching of alphabetic decoding skills is helpful for all children, harmful for none, and crucial for some.

Catherine Snow

For those who prefer to read, I summarize the characteristics of this style of teaching:

- “Explicit instruction is really about minimizing irrelevant information and highlighting and emphasizing the relevant information.”

- Remove all irrelevant information from your lectures and learning environment.

- Eliminate useless tangents from your teaching.

- Limit useless details in diagrams.

- Trim the number of words in your slides or notes.

- You might need to close the classroom door to limit distractions.

- I turn off the lights in my classroom so students can see the projector better. It also acts as a physical cue that it’s time for learning.

- This entails that the class needs to be well-behaved to maximize learning.

- Facing the teacher or the board.

- Silent unless to ask a question. In my classroom, this is typically done by raising one’s hand.

- No phones or distracting laptops unless needed for accommodations.

- No music or earphones.

- Students need to sit in a spot where they can see the board and hear the teacher.

- “Explicit instruction really starts with increasing supports when students don’t know much about the material. Explicit instruction really begins with breaking that material down if it’s really complex and presenting it in the sort of simplest, the least abstract, the most concrete way that that material can be presented.”

- “And this is the part where people kind of go awry is then right after that we’ve got after a small step presentation of what we’re teaching, we’ve got to check for understanding. You have to see, do the students know what I just said? Can they repeat it back to me in some way? This way, that whole caricature of explicit instruction of not being interactive is absolutely false. Explicit instruction is the most interactive system of teaching because with every small step you present, you’ve got to check to see if they know it.

- Do a turn and talk.

- I’m going to do a cold call.

- I’m going to do a mini whiteboard.

- I’m going to do finger voting.”

- “And as the students gain competence and familiarity with the material, we’re seeing that material slowly kind of eek its way in the long-term memory, right? And their expertise is growing. Now they’re not a total novice. Now there might be a relative expert. They’re getting kind of closer to being able to do that stuff on their own. That’s when we fade. We fade our guidance. We start having students kind of deal with problems that are maybe have a step you didn’t explain to them before. Or maybe there’s some irrelevant information you sort of inserted in there, but you know that will overwhelm them because they know how to do everything else.”

- “And finally, towards the end, you’re having kids work on that material completely on their own, perhaps even sprinkled in some extraneous information. And that to me is like, where you enhance transfer, you enhance like long-term retention of that material.”

- “So lots of scaffolding, breaking things down into small steps, checking for understanding along the way and gradually pulling back the guidance.”

Explicit instruction aims to minimize the frustration of students by explaining things as clearly as possible. It seeks to be the most efficient route to long-term changes in long-term memory (i.e. learning). Ideally, we would want all our students to master the curriculum expectations while feeling like it was doable and sometimes even easy. What is the utility of productive struggle if the learning outcomes are the same and often achieved in less time?

The direct instruction catchphrase is “I do. We do. You do.”. Let’s break down each phase of the lecture. You’ll notice that Rosenshine’s principles (in quotation marks) fit nicely with this framework.

I do.

- “Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning.”

- One way to do this is to start by doing a few targeted homework questions from the previous lectures.

- You can also give them a challenge.

- You can start with a short quiz. Auto grading can give you timely information on what needs to be taught again.

- Near the end of the unit, I often give students a few minutes to do a brain dump and try to connect the concepts using a mindmap or a cheatsheet.

- “Limit the amount of material students receive at one time.”

- “Give clear and detailed instructions and explanations.”

- “Ask a large number of questions and check for understanding.”

- “Think aloud and model steps.”

- “Provide models of worked-out problems.”

- “Provide many examples.”

We do.

- “Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step.”

- I have a timer where I give students a few minutes to practice. This makes it more formal and encourages them to take it more seriously.

- This is where I agree that good explicit instruction is extremely active. Students need to pay close attention to an explanation or a worked example and practice that skill immediately after. These modelling and practice cycles last anywhere between 1 and 15 minutes.

- I tease my students that they are on “cruise control” when they’re not actively participating and trying the practice problems. I expect all my students to use their calculators when necessary and not simply wait for me to punch it in.

- I tease students that neck problems occur to those who wait for the timer to run out before copying passively what I’m writing. We learn more when we first attempt a problem and then have to modify our answer based on the feedback.

- “Provide a high level of active practice for all students.”

- “Guide students as they begin to practice.”

- Scaffold problems.

- You can do the first few steps for them.

- You can do the diagram with them.

- You can highlight the key words.

- “Ask students to explain what they have learned.”

- This is where think, pair, share, collaborative work and mini tutors are handy.

- “Check the responses of all students.”

- I try to circulate and check their work. I might ask the students who got it right a more challenging question to make them think and stay engaged. Circulating also allows me to select a few students to share their solutions with the class. I often inform them in advance so they can prepare.

- I usually warn students about my cold calls so they have time to prepare. Building a culture where effort is what matters is key for cold calls.

- I do polls and votes all the time. Getting students to explain their vote before showing the answer is a great way to engage students.

- “Provide systematic feedback and corrections.”

- “Use more time to provide explanations.”

- “Reteach material when necessary.”

- “Prepare students for independent practice.”

- Students should obtain a high success rate through the lecture (around 85%).

You do.

- “Monitor students when they begin independent practice.”

- Circulate the classroom to encourage productive behaviour and answer questions.

- The homework should not introduce any new concepts. Eliminating homework disproportionately hurts students who struggle since they need more practice opportunities.

Explicit instruction is the bread and butter of teachers. It’s most effective for novice learners, which applies to the majority of K-12 students. For advanced students, there are many ways to differentiate instruction to keep them engaged. However, as discussed in our strategy, experts, by definition, already master the curriculum standards. Thus, the teacher has the imperative to adopt teaching methods that disproportionately benefit the students who need it most.

Retrieval Practice

We often think of learning as putting information into student’s heads. While that is true according to most definitions of learning, it turns out that pulling out information is beneficial to consolidate the learning. In other words, practice helps us learn. The act of pulling information out of our heads is more effective than rewatching the lecture or rereading the notes.

Spaced Repetition & Interleaving

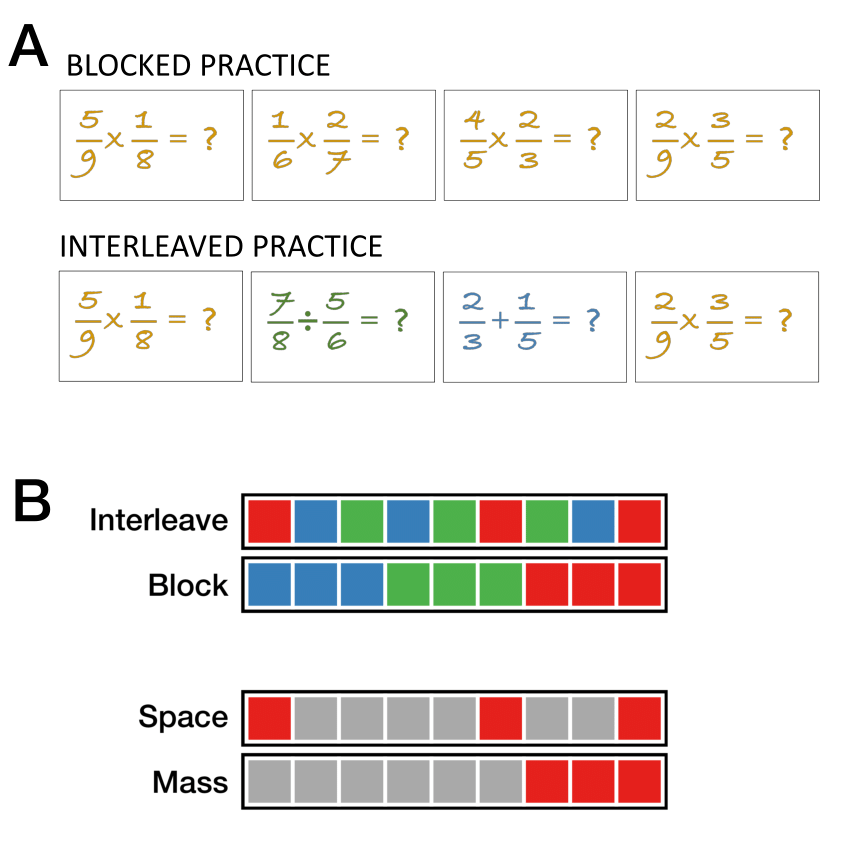

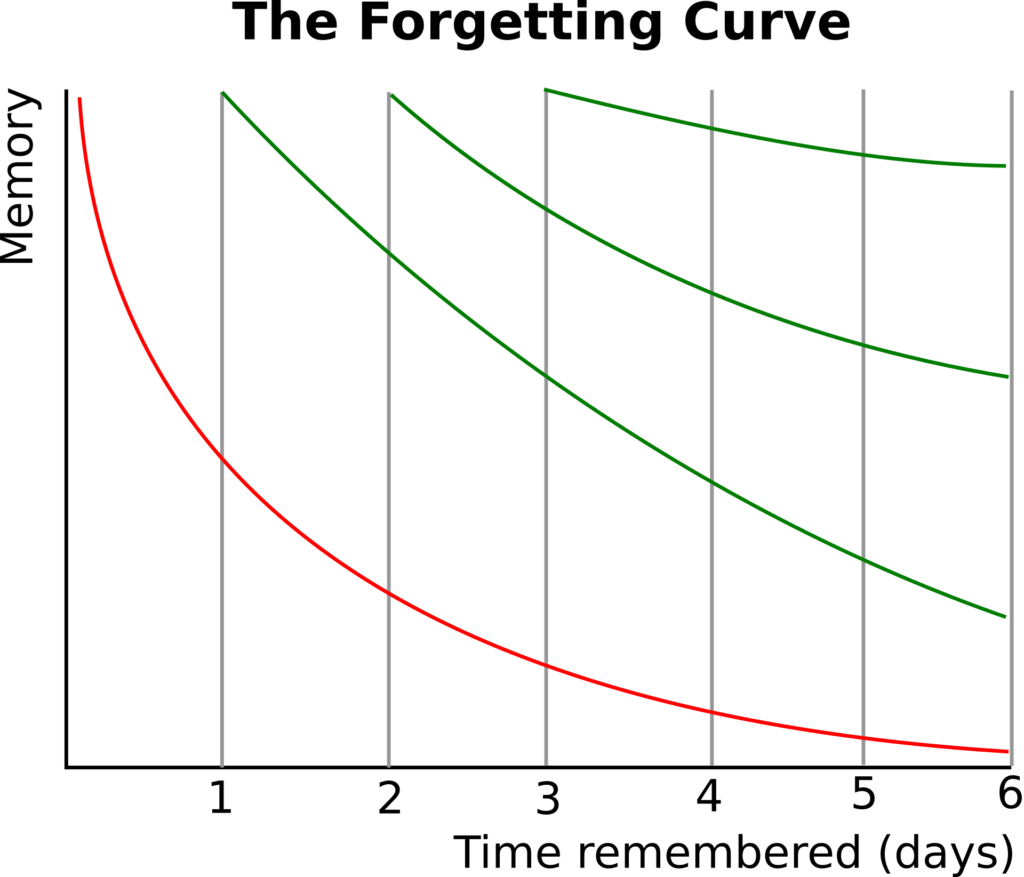

Even if we agree that retrieving information is more efficient for learning than consuming information, there are more efficient ways to perform retrieval practice. Two of those methods are spaced repetition and interleaved practice as illustrated below.

Both methods dampen the rate of forgetting and increase accuracy scores on recall tests.

This has implications for how we should sequence our lectures and problem sets. Some have proposed that we spiral the curriculum instead of teaching in discrete blocks. Others argue that we should block until a relative mastery and then interleave and return to the concepts. From experience, spiralling is often poorly executed and results in less learning, especially for struggling students. Below are suggestions of ways to reap the benefits of interleaving and spaced repetition without compromising the optimal success rate of 85%.

- Do a few homework problems the next day or a few days later.

- Have many low-stakes or no-stakes quizzes.

- Block practice during lectures and most of the homework. Interleave by the end of the homework, on quizzes, and on the test and exam review.

- Use flashcards and applications such as Anki or Quizlet to implement retrieval practice.

- When possible, sequence learning blocks in a way that builds on each other. Having a final exam is a terrific way to incentivize students to make connections and learn for the long term instead of cramming for the unit tests.

- Adopt mastery grading by allowing retakes or multiple opportunities to display their mastery of the curriculum’s expectations. Standards-based grading makes this more feasible since a student can only redo a few problems instead of an entire test.

- Teachers can provide class time to redo other versions of the unit tests throughout the semester to stay sharp. This could also be leveraged for mastery grading.

- Teachers should provide multiple opportunities to practice with homework, assignments, tutorials, labs, challenges, quizzes, practice tests, test reviews, questions in class, etc.

- There could be a cumulative homework section with a few interleaved practice problems from previous lectures.

Classroom Management

The objective is learning and not proper behaviour. We don’t want our students to be passive and obedient. Instead, we want them to be as active and engaged as possible to maximize learning. Classroom management sets the stage for learning to happen.

- Your relationship with the student is the most important variable to manage the classroom.

- Greet students as they enter.

- Learn their names on the first day if possible.

- Get to know them.

- Start the semester more serious and structured and gradually release the rigidity once students have adopted proper behaviours.

- Grade fairly. Students will be less likely to retaliate if they excel in the class and feel as though you want them to succeed.

- Communicate with parents often and be transparent about how you run your classrooms. The Google Classroom software automatically sends weekly emails to parents. Grades are published online. Hence, most parent communication can be automated. It’s a good idea to send a letter explaining the course expectations at the beginning of the semester.

- Be structured.

- Start on time.

- Show the plan for the period at the beginning of each day. This is a good time to talk about learning objectives.

- Show the plan for the entire semester on the first day and constantly refer to this plan. This gives students confidence in your ability and a sense of direction. A predictable and safe environment is key for learning and productive behaviours.

- Teach and model desired behaviour.

- You can’t expect your students to know what you want and be frustrated when they let you down.

- Practice desired behaviours at the start of the semester.

- Reward good behaviour.

- Adopt the principle of least force for interventions.

- Prevention should be your number one priority. It’ll take care of the majority of classroom management.

- Minor interventions such as emailing or calling the parents should take care of the rest. Once in a while, you may have to file an official report and take more extreme measures.

- Don’t suspend a student for forgetting their pencil. The consequences would ideally be logical and proportionate to the behaviour.

- Be patient. I’ve yet to be rewarded for getting agitated.

- Working in groups on the whiteboards is probably overrated. Social loafing, plagiarism and distractions are some of the factors that get in the way of learning. The amount of buzz in the classroom is no measure of engagement. The only measure of engagement is the amount of thinking and updating in student’s heads (which makes no sound).

- Rows and columns are probably the best class layout (Tom Bennett).

- Limit distractions.

- Mobile phones have no place in schools and stricter policies should be enforced (Tom Bennett & Daniel Willingham).

- Separate students if need be.

- I use a silent vibration alarm on my watch to remind me when there are 5 minutes left before each bell. That way, I never get caught teaching when the bell rings. It acts as a cue for consolidation.

Conclusion

Absorb what is useful, discard what is not, add what is uniquely your own.

Bruce Lee

The articles are far from exhaustive. Countless books are written about each section. My hope was to provide you with a general framework to think about teaching. We’ll never have completely mastered the art of teaching. It’s the journey of continual improvement that matters. What is your next step on this incredible journey?

Read This Next

- How To Teach

- Chalk & Talk podcast – Anna Stokke

- ResearchED Toronto Takeaways 2024

- The Tutor & The Gardener – My Teaching Philosophy

- How To Read Research

- Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction

- Designing mathematics standards in agreement with science

- How Learning Happens – Paul A. Kirschner & Carl Hendrick

- How Learning Happens – Nidhi Sachdeva

Footnotes

- I don’t think so. Replicable mastery of the curriculum standards is what we’re after. As long as it’s by the end of the course and we have sufficient evidence to be sure of this stable mastery, then a student should not be penalized for taking longer to get there. Consider the parachute example above as a thought experiment. ↩︎