How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett

How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman BarrettMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Somewhat repetitive book. Mind-boggling ideas. Not sure how far the constructivist views extend. If the theory is true, then there are exciting applications for medicine and therapy.

View all my reviews

Main Takeaways

- Better mental models lead to a better life.

- The best models are not always the most accurate ones but the most useful ones in an evolutionary sense.

- Precise words allow us to more efficiently match our concepts to the incoming data.

- Learning new words, journaling, meditation, healthy social interactions, and therapy can help us calibrate our models.

- Mood Meter app, Daylio app

- Responding to prediction errors like a scientist is crucial. Let natural selection of models and ideas take place.

- “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

- Reality is messy and rarely fits into neat little boxes.

- Models, concepts, words, and perceptions are all examples of our brain’s way to discretize the continuous world.

- A rainbow doesn’t have stripes.

- We downregulate the variation within categories and upregulate the variation between categories.

- They are all statistical summaries of populations of instances. The summary itself doesn’t exist.

- Models, concepts, words, and perceptions are all examples of our brain’s way to discretize the continuous world.

- There is a gap between how we experience the mind and how the mind actually works.Buddha was limited but managed to get a ton of insight through introspection.

- “The theory of constructed emotion and the classical view of emotion tell vastly different stories of how we experience the world. The classical view is intuitive—events in the world trigger emotional reactions inside of us. Its story features familiar characters like thoughts and feelings that live in distinct brain areas. The theory of constructed emotion, in contrast, tells a story that doesn’t match your daily life—your brain invisibly constructs everything you experience, including emotions. Its story features unfamiliar characters like simulation and concepts and degeneracy, and it takes place throughout the whole brain at once.”

- The brain is a complex system.

- Studying the mathematics and science of other complex systems may provide some insight into the functioning of the brain.

- Perhaps we will come to understand that chaos is the bottleneck preventing us from being able to predict the behaviour of the system.

- We can influence how we interpret the world to a large degree, but not to an infinite degree.

- Our predictions are bounded/tuned by physical stimuli.

- “Construction cannot make a solid wall unsolid (unless you have mutant superpowers), but you can redraw countries, redefine marriage, and decide who’s worthwhile and who isn’t.”

- “Sometimes, responsibility means that you’re the only one who can change things.”

- It’s not your fault, but it’s your responsibility.

- Beware of affective realism.

- Your affect in the present moment is not evidence of the validity of an event.

- Emotions can be intentionally influenced and perhaps mastered over time.

- Two pillars: Balanced Body-budget & Emotional granularity and accurate/useful mental models.

- Mastering emotions doesn’t imply no emotions. Rather that your emotions are useful in an evolutionary sense.

- Predictive Tuning Therapy (PTT)

- Bottom-up: Change sampling data in the present to influence future predictions.

- Behaviourally vote for who you want to be.

- Exercise, sleep, food, mindfulness, gratitude, journaling, breath, nature, information diet, social interactions, …

- Top-down: Recategorize stimuli so it is more useful.

- New words, new concepts, butterflies in formation, illnesses, the self, suffering versus pain, CBT, meditation, …

- Bottom-up: Change sampling data in the present to influence future predictions.

Book Notes

Intro: The Two-thousand-Year-Old Assumption

- The Classical View:

- “The classical view of emotion holds that we have many such emotion circuits in our brains, and each is said to cause a distinct set of changes, that is, a fingerprint.”

- “Our emotions, according to the classical view, are artifacts of evolution, having long ago been advantageous for survival, and are now a fixed component of our biological nature. As such, they are universal: people of every age, in every culture, in every part of the world should experience sadness more or less as you do—and more or less as did our hominin ancestors who roamed the African savanna a million years ago.”

- “Emotions are thus thought to be a kind of brute reflex, very often at odds with our rationality.”

- “This view of emotions has been around for millennia in various forms. Plato believed a version of it. So did Hippocrates, Aristotle, the Buddha, René Descartes, Sigmund Freud, and Charles Darwin. Today, prominent thinkers such as Steven Pinker, Paul Ekman, and the Dalai Lama also offer up descriptions of emotions rooted in the classical view.”

- “And yet . . . despite the distinguished intellectual pedigree of the classical view of emotion, and despite its immense influence in our culture and society, there is abundant scientific evidence that this view cannot possibly be true. Even after a century of effort, scientific research has not revealed a consistent, physical fingerprint for even a single emotion. When scientists attach electrodes to a person’s face and measure how facial muscles actually move during the experience of an emotion, they find tremendous variety, not uniformity. They find the same variety—the same absence of fingerprints—when they study the body and the brain. You can experience anger with or without a spike in blood pressure. You can experience fear with or without an amygdala, the brain region historically tagged as the home of fear.”

- The Constructivist View”

- “In short, we find that your emotions are not built-in but made from more basic parts. They are not universal but vary from culture to culture. They are not triggered; you create them.“

- “Emotions are real, but not in the objective sense that molecules or neurons are real. They are real in the same sense that money is real—that is, hardly an illusion, but a product of human agreement.”

- “The theory of constructed emotion might not fit the way you typically experience emotion and, in fact, may well violate your deepest beliefs about how the mind works, where humans come from, and why we act and feel as we do. But the theory consistently predicts and explains the scientific evidence on emotion, including plenty of evidence that the classical view struggles to make sense of.”

- “The history of science, however, has been a slow but steady march in the direction of construction.”

The Search for Emotion’s “Fingerprints”

- “My first “botched” experiment actually revealed a genuine discovery—that people often did not distinguish between feeling anxious and feeling depressed. My next seven experiments hadn’t failed either; they’d replicated the first one.”

- “A skilled interior designer can look at five shades of blue and distinguish azure, cobalt, ultramarine, royal blue, and cyan. My husband, on the other hand, would call them all blue. My students and I had discovered a similar phenomenon for emotions, which I described as emotional granularity.”

- Biological Fingerprints of Emotions:

- “The human face is laced with forty-two small muscles on each side.”

- “According to the classical view, each emotion is displayed on the face as a particular pattern of movements—a “facial expression.””

- “From this evidence, scientists concluded that emotion recognition is universal: no matter where you are born or grow up, you should be able to recognize American-style facial expressions like those in the photos. The only way expressions could be universally recognized, the reasoning went, is if they are universally produced: thus, facial expressions must be reliable, diagnostic fingerprints of emotion.”

- “As it turns out, facial EMG presents a serious challenge to the classical view of emotion. In study after study, the muscle movements do not reliably indicate when someone is angry, sad, or fearful; they don’t form predictable fingerprints for each emotion. At best, facial EMG reveals that these movements distinguish pleasant versus unpleasant feeling. Even more damning, the facial movements recorded in these studies do not reliably match the posed photos created for the basic emotion method.”

- “For example, the developmental psychologists Linda A. Camras and Harriet Oster and their colleagues videotaped babies from various cultures, employing a growling gorilla toy to startle them (to induce fear) or restraining their arm (to induce anger). Camras and Oster found, using FACS, that the range of babies’ facial movements in the two situations was indistinguishable. Nevertheless, when adults watched these videos, they somehow identified the infants in the gorilla film as afraid and infants in the arm restraint film as angry, even when Camras and Oster blanked out the babies’ faces electronically! The adults were distinguishing fear from anger based on the context, without seeing facial movements at all.”

- ““Is she saying that our culture has created these expressions, and we all have learned them?” Well . . . yes.”

- “The idea that a posed, so-called facial expression can trigger an emotional state is known as the facial feedback hypothesis. Allegedly, contorting your face into a particular configuration causes the specific physiological changes associated with that emotion in your body.”

- “The facial feedback hypothesis is highly controversial—there is wide disagreement on whether a full-blown emotional experience can be evoked this way.”

- “It showed some specificity for anger but not for the other emotions tested. That means the bodily responses for different emotions were too similar to be distinct fingerprints.”

- “Instead, the body’s orchestra of internal organs can play many different symphonies during happiness, fear, and the rest.”

- “It doesn’t mean that emotions are an illusion, or that bodily responses are random. It means that on different occasions, in different contexts, in different studies, within the same individual and across different individuals, the same emotion category involves different bodily responses.”

- “Variation, not uniformity, is the norm. These results are consistent with what physiologists have known for over fifty years: different behaviors have different patterns of heart rate, breathing, and so on to support their unique movements.”

- Population Thinking, Categories & Instances:

- “My window was the unexpected realization that an emotion is not a thing but a category of instances, and any emotion category has tremendous variety.”

- “A category, such as a species of animal, is a population of unique members who vary from one another, with no fingerprint at their core. The category can be described at the group level only in abstract, statistical terms.”

- “A species, you may recall, is a collection of diverse individuals, so it can be summarized only in statistical terms. The summary is an abstraction that does not exist in nature—it does not describe any individual member of the species.”

- “Large meta-analyses conclude that a single emotion category involves different bodily responses, not a single, consistent response.”

- “We can describe the instances of fear together by a pattern of brain activity, but this pattern is a statistical summary and need not describe any actual instance of fear.”

- “An emotion word such as “anger,” therefore, names a population of diverse instances, each one constructed to best guide action in the immediate circumstance.”

- “When you construct an emotional experience of your own, I call it an instance of emotion. I refer to fear, anger, happiness, sadness, and so on, in general as emotion categories, because each word names a population of diverse instances, just like the word “cookie” names a population of diverse instances.”

- Mental Organs

- “Overall, SM seemed fearless, and her damaged amygdalae seemed to be the reason. From this and other similar evidence, scientists concluded that a properly functioning amygdala was the brain center for fear.”

- “other brain networks are compensating for her missing amygdalae. So we have identical twins, with identical DNA, suffering from identical brain damage, living in highly similar environments, but one has some fear-related deficits while the other has none.”

- “These findings undermine the idea that the amygdala contains the circuit for fear. They point instead to the idea that the brain must have multiple ways of creating fear, and therefore the emotion category “Fear” cannot be necessarily localized to a specific region.

- “Brain regions like the amygdala are routinely important to emotion, but they are neither necessary nor sufficient for emotion.”

- “If the amygdala truly housed the circuit for fear, then this habituation should not occur—the circuit should fire in an obligatory way whenever it is presented with a triggering “fear” stimulus.”

- “In 2008, my lab along with neurologist Chris Wright demonstrated why the amygdala increases in activity in response to the basic emotion fear faces. The activity increases in response to any face—whether fearful or neutral—as long as it is novel (i.e., the test subjects have not seen it before).”

- “Interestingly, amygdala activity likewise increases during events usually considered non-emotional, such as when you feel pain, learn something new, meet new people, or make decisions.”

- Novelty = Potential usefulness to construct fear.

- “A core system is “one to many”: a single brain area or network contributes to many different mental states. The classical view of emotion, in contrast, considers particular brain areas to have dedicated psychological functions, that is, they are “one-to-one.” Core systems are therefore the antithesis of neural fingerprints.”

- “To be clear, I’m not saying that every neuron in the brain does exactly the same thing, nor that every neuron can stand in for every other. (That view is called equipotentiality, and it’s been long disproved.) I am saying that most neurons are multipurpose, playing more than one part, much as flour and eggs in your kitchen can participate in many recipes.”

- “Therefore we ask how, not where, emotions are made. The more neutral question, “How does the brain create an instance of fear?” does not presume a neural fingerprint behind the scenes, only that experiences an d perceptions of fear are real and worthy of study.”

- “The core systems that construct the mind interact in complex ways, without any central manager or chef to run the show. However, these systems cannot be understood independently like the disassembled parts of a machine, or like so-called emotion modules or organs. That’s because their interactions produce new properties that are not present in the parts alone.”

- “An instance of fear has irreducible, emergent properties not found in the ingredients alone…”

- Systems Thinking:

- Open systems:

- Many possible outcomes from the same starting point.

- Many different ways to reach the same outcome.

- Many-to-one: cities to state.

- One-to-many: state to cities.

- Many-to-many: patients to doctors.

- Are neural networks many-to-many? Yes.

- “Degeneracy means “many to one”: many combinations of neurons can produce the same outcome. In the quest to map emotion fingerprints in the brain, degeneracy is a humbling reality check.”

- “Brain circuitry operates by the many-to-one principle of degeneracy: instances of a single emotion category, such as fear, are handled by different brain patterns at different times and in different people. Conversely, the same neurons can participate in creating different mental states (one-to-many).”

- Open systems:

- The 3D Spatial Statistics of Neurons:

- “To make sense of this large amount of data, we divided the human brain virtually into tiny cubes called voxels, the 3-D version of pixels. Then, for every voxel in the brain during every emotion studied in every experiment, we recorded whether or not an increase in activation was reported. Now we could compute the probability that each voxel would show an increase in activation during the experience or perception of each emotion. When the probability was greater than chance, we called it statistically significant.”

- “In fact, no individual voxel appeared in all the scans of anger.”

- “Overall, we found that no brain region contained the fingerprint for any single emotion. Fingerprints are also absent if you consider multiple connected regions at once (a brain network), or stimulate individual neurons with electricity. The same results hold in experiments with other animals that allegedly have emotion circuits, such as monkeys and rats. Emotions arise from firing neurons, but no neurons are exclusively dedicated to emotion. For me, these findings have been the final, definitive nail in the coffin for localizing emotions to individual parts of the brain.”

- “Some scientists, using techniques from artificial intelligence, can train a software program to recognize many, many brain scans of people experiencing different emotions (say, anger and fear). The program computes a statistical pattern that summarizes each emotion category and then—here’s the cool part—can actually analyze new scans and determine if they are closer to the summary pattern for anger or fear. This technique, called pattern classification, works so well that it’s sometimes called “neural mind-reading.””

- “The statistical pattern for fear is not an actual brain state, just an abstract summary of many instances of fear. These scientists are mistaking a mathematical average for the norm.”

- “To make sense of this large amount of data, we divided the human brain virtually into tiny cubes called voxels, the 3-D version of pixels. Then, for every voxel in the brain during every emotion studied in every experiment, we recorded whether or not an increase in activation was reported. Now we could compute the probability that each voxel would show an increase in activation during the experience or perception of each emotion. When the probability was greater than chance, we called it statistically significant.”

Emotions Are Constructed

Experiential Blindness – See the Appendix section to be able to perceive this visual stimulus.

- Experiential Blindness

- “Most likely, you are in a state called experiential blindness, seeing only black blobs of unknown origin.”

- “Your past experiences—from direct encounters, from photos, from movies and books—give meaning to your present sensations. Additionally, the entire process of construction is invisible to you. No matter how hard you try, you cannot observe yourself or experience yourself constructing the image.”

- Simulation, Prediction, & Ambiguous Data

- “Simulations are your brain’s guesses of what’s happening in the world. In every waking moment, you’re faced with ambiguous, noisy information from your eyes, ears, nose, and other sensory organs. Your brain uses your past experiences to construct a hypothesis—the simulation—and compares it to the cacophony arriving from your senses. In this manner, simulation lets your brain impose meaning on the noise, selecting what’s relevant and ignoring the rest.”

- “Scientific evidence shows that what we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell are largely simulations of the world, not reactions to it.”

- “Simulation is the default mode for all mental activity.”

- “Construction treats the world like a sheet of pastry, and your concepts are cookie cutters that carve boundaries, not because the boundaries are natural, but because they’re useful or desirable. These boundaries have physical limitations of course; you’d never perceive a mountain as a lake. Not everything is relative.”

- “With concepts, your brain simulates so invisibly and automatically that vision, hearing, and your other senses seem like reflexes rather than constructions.”

- These purely physical sensations inside your body have no objective psychological meaning.”

- “Each of us understands the world in a way that is useful but not necessarily true in some absolute, objective sense.”

- “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

- The Theory of Constructed Emotions

- “The theory of constructed emotion and the classical view of emotion tell vastly different stories of how we experience the world. The classical view is intuitive—events in the world trigger emotional reactions inside of us. Its story features familiar characters like thoughts and feelings that live in distinct brain areas. The theory of constructed emotion, in contrast, tells a story that doesn’t match your daily life—your brain invisibly constructs everything you experience, including emotions. Its story features unfamiliar characters like simulation and concepts and degeneracy, and it takes place throughout the whole brain at once.”

- “A constructionist approach to emotion has a couple of core ideas. One idea is that an emotion category such as anger or disgust does not have a fingerprint. … Another core idea is that the emotions you experience and perceive are not an inevitable consequence of your genes.”

- “Particular concepts like “Anger” and “Disgust” are not genetically predetermined. Your familiar emotion concepts are built-in only because you grew up in a particular social context where those emotion concepts are meaningful and useful, and your brain applies them outside your awareness to construct your experiences.”

- “The macro structure of your brain is largely predetermined, but the microwiring is not.”

- “Neuroconstruction explains how human infants are born without the ability to recognize a face but can develop that capacity within the first few days after birth.”

- “The theory of constructed emotion, in contrast, proposes that emotions are not inborn, and if they are universal, it’s due to shared concepts. What’s universal is the ability to form concepts that make our physical sensations meaningful…”

- “Not every theory agrees on every assumption, but together they assert that emotions are made, not triggered; emotions are highly variable, without fingerprints; and emotions are not, in principle, distinct from cognitions and perceptions.”

- “The theory of constructed emotion incorporates elements of all three flavors of construction. From social construction, it acknowledges the importance of culture and concepts. From psychological construction, it considers emotions to be constructed by core systems in the brain and body. And from neuroconstruction, it adopts the idea that experience wires the brain.”

- “Construction incorporates the latest scientific findings about Darwinian natural selection and population thinking. For example, the many-to-one principle of degeneracy—many different sets of neurons can produce the same outcome—brings about greater robustness for survival. The one-to-many principle—any single neuron can contribute to more than one outcome—is metabolically efficient and increases the computational power of the brain. This kind of brain creates a flexible mind without fingerprints.”

- “An emotion is your brain’s creation of what your bodily sensations mean, in relation to what is going on around you in the world.”

- “In every waking moment, your brain uses past experience, organized as concepts, to guide your actions and give your sensations meaning. When the concepts involved are emotion concepts, your brain constructs instances of emotion.”

- “My experience in the coffee shop, where I felt attraction when I had the flu, would be called an error or misattribution in the classical view, but it’s no more a mistake than seeing a bee in a bunch of blobs.”

- “Emotions are not reactions to the world. You are not a passive receiver of sensory input but an active constructor of your emotions. From sensory input and past experience, your brain constructs meaning and prescribes action. If you didn’t have concepts that represent your past experience, all your sensory inputs would just be noise.”

- “Therefore we ask how, not where, emotions are made. The more neutral question, “How does the brain create an instance of fear?” does not presume a neural fingerprint behind the scenes, only that experiences and perceptions of fear are real and worthy of study.”

- “Usually, you experience interoception only in general terms: those simple feelings of pleasure, displeasure, arousal, or calmness that I mentioned earlier. Sometimes, however, you experience moments of intense interoceptive sensations as emotions. That is a key element of the theory of constructed emotion. In every waking moment, your brain gives your sensations meaning. Some of those sensations are interoceptive sensations, and the resulting meaning can be an instance of emotion.”

- Affective Realism:

- “We must not confuse physical reality, such as changes in heart rate or widened eyes, with the social reality of emotion concepts.”

- “Perceptions of emotion are guesses, and they’re “correct” only when they match the other person’s experience; that is, both people agree on which concept to apply. Anytime you think you know how someone else feels, your confidence has nothing to do with actual knowledge. You’re just having a moment of affective realism.”

- “Anytime you have a gut feeling that you know something to be true, that’s affective realism.”

- “Your affect is not evidence that the science is good or bad.”

- Architects of Emotions

- “I also avoid verbs like “triggering” emotion, and phrases like “emotional reaction” and emotions “happening to you.” Such wording implies that emotions are objective entities. Even when you feel no sense of agency when experiencing emotion, which is most of the time, you are an active participant in that experience.”

- “We don’t recognize emotions or identify emotions: we construct our own emotional experiences, and our perceptions of others’ emotions, on the spot, as needed, through a complex interplay of systems. Human beings are not at the mercy of mythical emotion circuits buried deep within animalistic parts of our highly evolved brain: we are arc hitects of our own experience.”

- “Your river of feelings might feel like it’s flowing over you, but actually you’re the river’s source.”

- “That means, in effect, that you construct the environment in which you live. You might think about your environment as existing in the outside world, separate from yourself, but that’s a myth. You (and other creatures) do not simply find yourself in an environment and either adapt or die. You construct your environment—your reality—by virtue of what sensory input from the physical environment your brain selects; it admits some as information and ignores some as noise. And this selection is intimately linked to interoception. Your brain expands its predictive repertoire to include anything that might impact your body budget, in order to meet your body’s metabolic demands. This is why affect is a property of consciousness.”

- “Emotions are not reactions to the world; they are your constructions of the world.”

- “Your personal experience, therefore, is actively constructed by your actions. You tweak the world, and the world tweaks you back. You are, in a very real sense, an architect of your environment as well as your experience. Your movements, and other people’s movements in turn, influence your own incoming sensory input. These incoming sensations, like any experience, can rewire your brain. So you’re not only an architect of your experience, you’re also an electrician.”

The Myth of Universal Emotions

The growing economy of emotion-reading gadgets and apps also assumes universality, as if emotions can be read in the face or in patterns of bodily changes in the absence of context, as easily as reading words on a page. The sheer amount of time, effort, and money going into these efforts is mind-boggling.

Lisa Feldman Barrett – How Emotions Are Made

- Experimental Biases:

- “In one of the first free labeling studies ever conducted, subjects named the faces with the expected emotion words (or synonyms) only 58 percent of the time, and in subsequent studies the results were even lower. In fact, if you ask a more neutral question without referring to emotion at all—“What word best describes what’s going on inside this person?”—the performance is even worse.”

- “Instead, the patients produced only positive, negative, and neutral piles, an arrangement that merely reflects pleasant versus unpleasant feeling.”

- “Happiness” is usually the only pleasant emotion category that is tested using the basic emotion method, so it’s trivial for subjects to distinguish it from the negative categories.

- “There is one emotion category that people seem able to perceive without the influence of emotion concepts: happiness. Regardless of the experimental method used, people in numerous cultures agree that smiling faces and laughing voices express happiness. So “Happy” might be the closest thing we have to a universal emotion category with a universal expression.”

- “And consider this fun fact: the historical record implies that ancient Greeks and Romans did not smile spontaneously when they were happy. The word “smile” doesn’t even exist in Latin or Ancient Greek. Smiling was an invention of the Middle Ages, and broad, toothy-mouthed smiles (with crinkling at the eyes, named the Duchenne smile by Ekman) became popular only in the eighteenth century as dentistry became more accessible and affordable.”

- “Himba and Hadza emotion concepts, for example, appear to be more focused on actions.”

- “In the long run, scientists who still subscribe to the basic emotion method are very likely helping to create the universality that they believe they are discovering.”

- “People will use whatever measure you give them to describe how they feel.”

The Origin of Feeling

Affect leads us to believe that objects and people in the world are inherently negative or positive.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT – HOW EMOTIONS ARE MADE

- Intrinsic Activity:

- “The intrinsic activity in your brain is not random; it is structured by collections of neurons that consistently fire together, called intrinsic networks.”

- “Intrinsic networks are considered one of neuroscience’s great discoveries of the past decade.5 You might wonder what this hotbed of continuous, intrinsic activity is accomplishing, besides keeping your heart beating, your lungs breathing, and your other internal functions working smoothly. In fact, intrinsic brain activity is the origin of dreams, daydreams, imagination, mind wandering, and reveries, which we collectively called simulation in chapter 2. It also ultimately produces every sensation you experience, including your interoceptive sensations, which are the origins of your most basic pleasant, unpleasant, calm, and jittery feelings.6…”

- “In brain-imaging experiments, when we show photographs to test subjects or ask them to perform tasks, only a small portion of the signal we measure is due to the photos and tasks; most of the signal represents intrinsic activity.”

- Predictions:

- “Even single-celled animals engage in statistical learning and then prediction: they not only respond to changes in their environment but anticipate them.”

- “At the level of brain cells, prediction means that the neurons over here, in this part of your brain, tweak the neurons over there, in that part of your brain, without any need for a stimulus from the outside world. Intrinsic brain activity is millions and millions of nonstop predictions.”

- “Prediction is such a fundamental activity of the human brain that some scientists consider it the brain’s primary mode of operation.”

- “Predictions not only anticipate sensory input from outside the skull but explain it.”

- “Once the prediction is confirmed by an actual apple, the prediction has, in effect, explained the visual sensations as being an apple.”

- “If your brain predicts perfectly—say, you predicted a McIntosh apple as you came upon a display of them—then the actual visual input of the apple, captured by your retina, carries no new information beyond the prediction. The visual input merely confirms the prediction is correct, so the input needn’t travel any further in the brain. The neurons in your visual cortex are already firing as they should be. This efficient, predictive process is your brain’s default way of navigating the world and making sense of it.

- “Your brain also uses prediction to initiate your body’s movements, like reaching your arm out to pick up an apple or dashing away from a snake. These predictions occur before you have any conscious awareness or intent about moving your body. Neuroscientists and psychologists call this phenomenon “the illusion of free will.” The word “illusion” is a bit of a misnomer; your brain isn’t acting behind your back. You are your brain, and the whole cascade of events is caused by your brain’s predictive powers. It’s called an illusion because movement feels like a two-step process—decide, then move—when in fact your brain issues motor predictions to move your body well before you become aware of your intent to move. And even before you actually encounter the apple (or the snake)!”

- “If your brain were merely reactive, it would be too inefficient to keep you alive.”

- “A reactive brain would also be too expensive, metabolically speaking, because it would require more interconnections than it could maintain.”

- “You are not a reactive animal, wired to respond to events in the world. When it comes to your experiences and perceptions, you are much more in the driver’s seat than you might think. You predict, construct, and act. You are an architect of your experience.”

- “Your brain is predictive, not reactive.”

- “The stimulus-response brain is a myth, brain activity is prediction and correction, and we construct emotional experiences outside of awareness.

- Body-Budgeting:

- “From your brain’s point of view, locked inside the skull, your body is just another part of the world that it must explain.”

- “So, your brain models the world from the perspective of someone with your body.”

- Might be crucial for AI and it’s related to embodied cognition.

- “To simplify our discussion drastically, I’ll describe this network as having two general parts with distinct roles. One part is a set of brain regions that send predictions to the body to control its internal environment: speed up the heart, slow down breathing, release more cortisol, metabolize more glucose, and so on. We’ll call them your body-budgeting regions.* The second part is a region that represents sensations inside your body, called your primary interoceptive cortex.”

- “People call cortisol a “stress hormone,” but this is a mistake. Cortisol is released whenever you need a surge of energy, which happens to include the times when you are stressed. Its main purpose is to flood the bloodstream with glucose to provide immediate energy to cells, allowing, for example, muscle cells to stretch and contract so you can run.”

- “Every simulation, whether it becomes an emotion or not, impacts your body budget. As it turns out, people spend at least half their waking hours simulating rather than paying attention to the world around them, and this pure simulation strongly drives their feelings.”

- “Other people regulate your body budget too. When you interact with your friends, parents, children, lovers, teammates, therapist, or other close companions, you and they synchronize breathing, heart beats, and other physical signals, leading to tangible benefits.”

- “If you’re standing at the bottom of a hill with friends, it will appear less steep and easier to climb than if you are alone.”

- “The thing is, a bad feeling doesn’t always mean something is wrong. It just means you’re taxing your body budget. When people exercise to the point of labored breathing, for example, they feel tired and crappy well before they run out of energy. When people solve math problems and perform difficult feats of memory, they can feel hopeless and miserable, even when they are performing well.”

- If you’ve ever heard the advice, “Wait 20 minutes before you take a second helping, to see if you’re really still hungry,” now you know why it works. Whenever you make a big deposit or withdrawal from your body budget—eating, exercising, injuring yourself—you might have to wait for your brain to catch up. Marathon runners learn this; they feel fatigue early in the race when their body budget is still solvent, so they keep running until the unpleasant feeling goes away. They ignore the affective realism that insists they’re out of energy.

- David Goggins 40% Rule.

- “You’ve just learned that the sensations you feel from your body don’t always reflect the actual state of your body. That’s because familiar sensations like your heart beating in your chest, your lungs filling with air, and, most of all, the general pleasant, unpleasant, aroused, and quiescent sensations of affect are not really coming from inside your body. They are driven by simulations in your interoceptive network.”

- “Your body-budgeting regions are like a mostly deaf scientist: they make predictions but have a hard time listening to the incoming evidence.”

- Affect Versus Emotions:

- “Affect is the general sense of feeling that you experience throughout each day. It is not emotion but a much simpler feeling with two features. The first is how pleasant or unpleasant you feel, which scientists call valence. … The second feature of affect is how calm or agitated you feel, which is called arousal.”

- “The psychologist James A. Russell developed a way of tracking affect, and it’s become popular among clinicians, teachers, and scientists. He showed that you can describe your affect in the moment as a single point on a two-dimensional space called a circumplex, a circular structure with two dimensions, as in figure 4-5. Russell’s two dimensions represent valence and arousal, with distance from the origin representing intensity.”

- Track this with Mood Meter app.

- “Certainly infants feel pleasure and distress from birth, and affect-related concepts (pleasant/unpleasant) show up by three to four months of age. But there’s a lot of research to indicate that adult-like emotion concepts develop later. Just how much later is an open question.”

- “Affect, you may recall, depends on interoception. That means affect is a constant current throughout your life, even when you are completely still or asleep.”

- “In this sense, affect is a fundamental aspect of consciousness, like brightness and loudness.”

- “Interoception is not a mechanism dedicated to manufacturing affect. Interoception is a fundamental feature of the human nervous system, and why you experience these sensations as affect is one of the great mysteries of science. Interoception did not evolve for you to have feelings but to regulate your body budget.”

- “When the neurosurgeons turn on the electrodes, Mayberg’s patients report immediate relief from their agony. As the electrical current is turned off and on, the patients’ crippling wave of dread approaches and recedes in synchrony with the stimulation. Mayberg’s remarkable work might represent the first time in scientific history that direct stimulation of the human brain has consistently changed people’s affective feelings, potentially leading to new treatments for mental illness.”

- “While predictive brain circuitry is important for affect, it likely is not necessary.”

- “Affect is the general sense of feeling that you experience throughout each day. It is not emotion but a much simpler feeling with two features. The first is how pleasant or unpleasant you feel, which scientists call valence. … The second feature of affect is how calm or agitated you feel, which is called arousal.”

- Affective Realism

- “When you experience affect without knowing the cause, you are more likely to treat affect as information about the world, rather than your experience of the world.”

- “This phenomenon is called affective realism, because we experience supposed facts about the world that are created in part by our feelings.”

- The change in her body budget, which she’s experiencing as affect, might not have anything to do with you.”

- “Affect leads us to believe that objects and people in the world are inherently negative or positive.”

- “The phrase “an unpleasant image” is really shorthand for “an image that impacts my body budget, producing sensations that I experience as unpleasant.””

- “People employ affect as information, creating affective realism, throughout daily life. Food is “delicious” or “bland.” Paintings are “beautiful” or “ugly.” People are “nice” or “mean.” Women in certain cultures must wear scarves and wigs so as not to “tempt men” by showing a bit of hair. Sometimes affective realism is helpful, but it also shapes some of humanity’s most troubling problems.”

- “People like to say that seeing is believing, but affective realism demonstrates that believing is seeing.”

- “You might think that in everyday life, the things you see and hear influence what you feel, but it’s mostly the other way around: that what you feel alters your sight and hearing. Interoception in the moment is more influential to perception, and how you act, than the outside world is.”

- Prediction Error & Learning:

- “Through prediction and correction, your brain continually creates and revises your mental model of the world.”

- “Prediction errors aren’t problems. They’re a normal part of the operating instructions of your brain as it takes in sensory input. Without prediction error, life would be a yawning bore. Nothing would be surprising or novel, and therefore your brain would never learn anything new.”

- “Predictions become simulations of sensations and movement. These simulations are compared to actual sensory input from the world. If they match, the predictions are correct and the simulation becomes your experience. If they don’t match, your brain must resolve the errors.” But how???????

- “When prediction errors occur, the brain can resolve them in two general ways. The first, which we’ve just seen in my lame attempt to catch a baseball, is that the brain can be flexible and change the prediction. … The brain’s second alternative is to be stubborn and stick with the original prediction. It filters the sensory input so it’s consistent with the prediction.”

- “It can be a responsible scientist and change its predictions to respond to the data. Your brain can also be a biased scientist and selectively choose data that fits the hypotheses, ignoring everything else. Your brain can also be an unscrupulous scientist and ignore the data altogether, maintaining that its predictions are reality. Or, in moments of learning or discovery, your brain can be a curious scientist and focus on input. And like the quintessential scientist, your brain can run armchair experiments to imagine the world: pure simulation without sensory input or prediction error.”

- “A newborn is experientially blind to a great extent. Not surprisingly, the infant brain does not predict well. A grown-up brain is dominated by prediction, but an infant brain is awash in prediction error. So babies must learn about the world from sensory input before their brains can model the world.”

- Hypothesis based on Molecule of More that infants have higher dopamine levels than adults based on more prediction error.

- Bounded Hallucination:

- “In a sense, your brain is wired for delusion: through continual prediction, you experience a world of your own creation that is held in check by the sensory world.”

- “The world often takes a backseat to your predictions. (It’s still in the car, so to speak, but is mostly a passenger.)”

- “Your experiences are not a window into reality. Rather, your brain is wired to model your world, driven by what is relevant for your body budget, and then you experience that model as reality.”

- “What we experience as “certainty”—the feeling of knowing what is true about ourselves, each other, and the world around us—is an illusion that the brain manufactures to help us make it through each day. Giving up a bit of that certainty now and then is a good idea.”

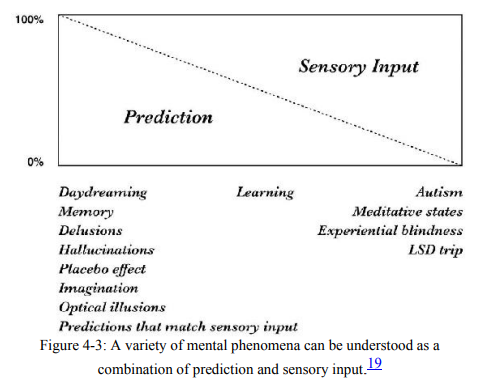

- Sensory Input Versus Prediction Landscape

- Tradeoff relationship (linear?)

- Zone of Proximal Development in the middle = Learning

- The middle zone is probably where plasticity happens?

- Rationality

- “You might believe that you are a rational creature, weighing the pros and cons before deciding how to act, but the structure of your cortex makes this an implausible fiction. Your brain is wired to listen to your body budget. Affect is in the driver’s seat and rationality is a passenger.”

- “Antonio Damasio, in his bestseller Descartes’ Error, observes that a mind requires passion (what we would call affect) for wisdom.”

- “Affect is not just necessary for wisdom; it’s also irrevocably woven into the fabric of every decision.”

- “You cannot overcome emotion through rational thinking, because the state of your body budget is the basis for every thought and perception you have, so interoception and affect are built into every moment.”

- “The bottom line is this: the human brain is anatomically structured so that no decision or action can be free of interoception and affect, no matter what fiction people tell themselves about how rational they are.”

- “You see, your brain’s body-budgeting regions are major hubs. Through their massive connections, they broadcast predictions that alter what you see, hear, and otherwise perceive and do. That’s why, at the level of brain circuitry, no decision can be free of affect.”

- Triune Brain Myth

- “This illusory arrangement of layers, which is sometimes called the “triune brain,” remains one of the most successful misconceptions in human biology.”

- “Modern neuroscience, however, has shown that the so-called limbic system is a fiction, and experts in brain evolution no longer take it seriously, let alone consider it a system. Accordingly, it’s not the home of emotion in the brain, which is unsurprising because no single brain area is dedicated to emotion.”

- “This approach is still influential, even though the amygdala is not the home of any emotion, the prefrontal cortex does not house cognition, and emotion and cognition are whole-brain constructions that cannot regulate each other.”

Concepts, Goals, and Words

- Discretizing the Continuous World:

- “The objects you see, the sounds you hear, the odors you smell, the touches you feel, the flavors you taste, and the interoceptive sensations you experience as aches and pains and affect . . . they all involve continuous sensory signals that are highly variable and ambiguous as they reach your brain. Your brain’s job is to predict them before they arrive, fill in missing details, and find regularities where possible, so that you experience a world of objects, people, music, and events, not the “blooming, buzzing confusion” that is really out there.”

- “This means that an instance of an emotion concept helps to make sense of longer continuous streams of sensory input, dividing them into distinct events.”

- Vision:

- “Why do you and I see stripes? Because we have mental concepts for colors like “Red,” “Orange,” and “Yellow.” Your brain automatically uses these concepts to group together the wavelengths in certain ranges of the spectrum, categorizing them as the same color. Your brain downplays the variations within each color category and magnifies the differences between the categories, causing you to perceive bands of color.”

- “If you think of your field of vision as a big TV screen, then your slight eye movement just changed millions of pixels on that screen. And yet, you did not experience blurry streaks across your visual field. That’s because you don’t see the world in terms of pixels: you see objects, and they changed very little as you moved your eyes. You perceive low-level regularities like lines, contours, streaks, and blurs, as well as higher-level regularities like complex objects and scenes. Your brain learned these regularities as concepts long ago, and it uses those concepts now to categorize your continually changing visual input.”

- “Infants are born unable to see faces. They have no perceptual concept of “Face” and so are experientially blind. They quickly learn to see human faces, however, from the perceptual regularities alone: two eyes up top, a nose in the middle, and a mouth.”

- “Your brain was not programmed by nature to recognize facial expressions and other so-called emotional displays and then to reflexively act on them. The emotional information is in your perception. Nature provided your brain with the raw materials to wire itself with a conceptual system, with input from a chorus of helpful adults who spoke emotion words to you in a deliberate and intentional way.”

- Sound:

- “Human speech also is continuous—a stream of sound—yet when you listen to your native language, you hear discrete words. How does that happen? Once again, you use concepts to categorize the continuous input.”

- “An incredible 50 percent of the words we hear cannot be understood out of context (when presented in isolation).”

- “Human speech also is continuous—a stream of sound—yet when you listen to your native language, you hear discrete words. How does that happen? Once again, you use concepts to categorize the continuous input.”

- “Your perceptions are so vivid and immediate that they compel you to believe that you experience the world as it is, when you actually experience a world of your own construction.”

- “Your own perceptions are not like a photograph of the world. They are not even a painting of photographic quality, like a Vermeer. They are more like a Van Gogh or Monet. (Or on a very bad day, perhaps a Jackson Pollock.)”

- Categories & Concepts:

- “Concepts also encourage us not to see things that are present.”

- “Categorization is business as usual for your brain, and it explains how emotions are made without needing fingerprints.”

- “Philosophers and scientists define a category as a collection of objects, events, or actions that are grouped together as equivalent for some purpose. They define a concept as a mental representation of a category. Traditionally, categories are supposed to exist in the world, while concepts exist in your head.”

- “Your brain downplays the differences between the members of a category, such as the diverse shades of red roses in a botanical garden, to consider those members equivalent as “red.” Your brain also magnifies differences between members and nonmembers (say, red versus pink roses) so that you perceive firm boundaries between them.”

- “Any variation from bee to bee is considered irrelevant to the fact that they are bees. You might notice a parallel here to the classical view of emotion, in which every instance of the category “Fear” is similar, and instances of “Fear” are distinct from instances of “Anger.”

- “In the 1970s, the classical view of concepts finally collapsed. Well, except in the science of emotion.”

- “From the ashes of classical concepts, a new view arose. It said that a concept is represented in the brain as the best example of its category, known as the prototype.”

- “Variation from the prototype is perfectly fine, but not too much variation: a bee is still not a bird, even though it has wings and can fly.”

- “Thus, concepts aren’t fixed definitions in your brain, and they’re not prototypes of the most typical or frequent instances. Instead, your brain has many instances—of cars, of dot patterns, of sadness, or anything else—and it imposes similarities between them, in the moment, according to your goal in a given situation.”

- “Concepts are not static but remarkably malleable and context-dependent, because your goals can change to fit the situation.”

- “In fact, the goal is the only thing that holds together the category.”

- Might also be important for AI.

- “Emotion concepts are goal-based concepts.”

- “Your brain weighs its predictions based on probabilities; they compete to explain what caused your sensations, and they determine what you perceive, how you act, and what you feel in this situation. Ultimately, the most probable predictions become your perception.”

- “Concepts are linked to everything you do and perceive. And as you learned in the previous chapter, everything you do and perceive is linked to your body budget. Therefore, concepts must be linked to your body budget. And, in fact, they are.”

- “This is categorization with emotion concepts. You aren’t detecting or recognizing emotion in someone’s face. You aren’t recognizing a physiological pattern in your own body. You are predicting and explaining the meaning of those sensations based on probability and experience.”

- “When we say these instances are “grouped” as a concept, be aware that there is no “grouping” stored anywhere in Sophia’s brain. Any given concept is not represented in the information flow among one single set of neurons; each concept is itself a population of instances, and these instances are represented in different patterns of neurons on each occasion. (This is degeneracy.) The concept is constructed in the moment, ad hoc. And among these myriad instances, one of them will be the most similar (by pattern matching) to Sophia’s current situation. That’s what we’ve been calling the “winning instance.””

- “I’ve been calling this process “categorization,” but it’s known by many other names in science. Experience. Perception. Conceptualization. Pattern completion. Perceptual inference. Memory. Simulation. Attention. Morality. Mental Inference.”

- Words & Communication:

- “Successful communication requires that you and your friend are using synchronized concepts.”

- “Babies are born able to hear the differences between all sounds in all languages, but by the time they reach one year of age, statistical learning has reduced this ability to the sounds contained only in the languages they have heard spoken by live humans. Babies become wired for their native languages by statistical learning.”

- “To build a purely mental concept, you need another secret ingredient: words.”

- “The developmental psychologists Sandra R. Waxman and Susan A. Gelman, leaders in this area of research, hypothesize that words invite an infant to form a concept, but only when adults speak w ith intent to communicate: “Look, sweetie: a flower!””

- “When the same experiment was performed with audio tones instead of human speech, the effect never materialized.”

- “Spoken words give the infant brain access to information that can’t be found by observing the world and resides only in the minds of other people, namely, mental similarities: goals, intentions, preferences.”

- “Words encourage infants to form goal-based concepts by inspiring them to represent things as equivalent. In fact, studies show that infants can more easily learn a goal-based concept, given a word, than a concept defined by physical similarity without a word.”

- “So far, my hypothesis about emotion words is only reasoned speculation because the science of emotion is missing a systematic exploration of this question.”

- “How do you get a concept without a word? Well, your brain’s conceptual system has a special power called conceptual combination. It combines existing concepts to create your very first instance of a novel concept of emotion.”

- “That is, words invite you to believe in an essence, and that process is conceivably the psychological origin of essentialism.”

- “The very words that help us to learn concepts can also trick us into believing that their categories reflect firm boundaries in nature.”

- “Each summary is like a little imaginary essence, invented by your brain to represent that a bunch of instances from your past are similar.”

- “Today’s textbooks in psychology and neurology still hold up Broca’s area as the clearest example of localized brain function, even as neuroscience has shown that the region is neither necessary nor sufficient for language.”

- Emotional Granularity:

- “Strictly speaking, you don’t need an emotion word to construct an instance of that emotion, but it’s easier when you have a word. If you want the concept to be efficient, and you want to transmit the concept to others, then a word is pretty handy.”

- “Conceptual combination plus words equals the power to create reality.”

- “When a mind has an impoverished conceptual system for emotion, can it perceive emotion? From scientific experiments in our own lab, we know that the answer is generally no.”

- “The way around this conundrum is to study people who have a naturally impoverished conceptual system for emotion, a condition called alexithymia, which by one estimate affects about 10 percent of the world’s population.”

- Utility of inventing our unique emotion words:

- “But sometimes we are blessed with supervisors who personify the German emotion word Backpfeifengesicht, meaning “a face in need of a fist.””

How the Brain Makes Emotions

- Metabolic Efficiency:

- “YouTube separates the video’s similarities from its differences to speed up transmission, and software on your computer or phone assembles the pieces into a cohesive video. The human brain does much the same thing when it processes prediction error.”

- “Eventually, the infant’s brain forms summary representations for enough visual concepts that she can see one stable object, despite incredible variation in low-level sensory details.”

- “Think about it: each of your eyes transmits millions of tiny pieces of information to your brain in a moment, and you simply see “a book.””

- “In this manner, an infant’s brain distills widely dispersed firing patterns for individual senses into one multisensory summary.”

- “Preciseness leads to efficiency; this is a biological payoff of higher emotional granularity.”

- This is support for Peterson’s Rule #10: ” Be precise in your speech.”

- “Words seed your concepts, concepts drive your predictions, predictions regulate your body budget, and your body budget determines how you feel. Therefore, the more finely grained your vocabulary, the more precisely your predicting brain can calibrate your budget to your body’s needs.”

- “Just as an individual brain takes advantage of redundancy, compressing information into similarities and differences, multiple brains take advantage of one another’s redundancies (that we’re in the same culture and learned the same concepts) and wire each other. In effect, evolution improves its efficiency via human culture, and we pass culture to our offspring by wiring their brains.”

- “A brain with high complexity and degeneracy brings distinct advantages. It can create and carry more information. It’s more robust and reliable, with multiple paths to get to the same end. It’s more resistant to injury and illness.”

- “Natural selection favors a complex brain. Complexity, not rationality, makes it possible for you to be an architect of your experience. Your genes allow you, and others, to remodel your brain and therefore your mind.”

- Winning Instances:

- “Ultimately, through a process we’ll discuss shortly, your brain selects a winning instance of “Anger” that best fits your goal in this particular situation. The winning instance determines how you behave and what you experience. This process is categorization.”

- “Once again, the prediction that is most similar to the current situation becomes her experience—an instance of emotion.”

- “When your brain “constructs an instance of a concept,” such as an instance of “Happiness,” that is equivalent to saying your brain “issues a prediction” of happiness.”

- “”Which predictions should be the winners? Which sensory input is important, and which is just noise? Your brain has a network to help resolve these uncertainties, known as your control network. This is the same network that transforms an infant’s “lantern” of attention into the adult “spotlight” you have now.”

- “Which predictions should be the winners? Which sensory input is important, and which is just noise? Your brain has a network to help resolve these uncertainties, known as your control network. This is the same network that transforms an infant’s “lantern” of attention into the adult “spotlight” you have now.”

- “The result is akin to natural selection, in which the instances most suitable to the current environment survive to shape your perception and action.”

- Memory:

- “The Nobel laureate and neuroscientist Gerald M. Edelman called your experiences “the remembered present.””

- Meaning:

- “Emotions are meaning. They explain your interoceptive changes and corresponding affective feelings, in relation to the situation. They are a prescription for action. The brain systems that implement concepts, such as the interoceptive network and the control network, are the biology of meaning-making.”

Emotions as Social Reality

Just get a couple of people to agree that something is real and give it a name, and they create reality. All humans with a normally functioning brain have the potential for this little bit of magic, and we use it all the time.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT – HOW EMOTIONS ARE MADE

- What is Objective Reality?

- “In the theory of constructed emotion, however, the dividing line between brain and world is permeable, perhaps nonexistent.”

- “A sound, therefore, is not an event that is detected in the world. It is an experience constructed when the world interacts with a body that detects changes in air pressure, and a brain that can make those changes meaningful.”

- “And in the absence of a brain, there is no experience of color at all, only reflected light in the world.”

- “For instance, to the Berinmo people of Papua New Guinea, apples reflecting light at 600 nanometers are experienced as brownish, because Berinmo concepts for color divide up the continuous spectrum differently.”

- “Changes in air pressure and wavelengths of light exist in the world, but to us, they are sounds and colors.”

- “A third and final riddle is, “Are emotions real?”

- “But here, the answer is a bit more complex, because it depends on what we mean by “real.””

- They are supposed to exist in the natural world whether or not humans are present—that is, they are thought to be perceiver-independent categories. If all human life left this planet tomorrow, subatomic particles would still be here.”

- “We constantly mistake perceiver-dependent concepts—flowers, weeds, colors, money, race, facial expressions, and so on—for perceiver-independent reality. Many concepts that people consider to be purely physical are in fact beliefs about the physical, such as emotions, and many that appear to be biological are actually social.”

- “Science, however, tells us that emotions require a perceiver, just as colors and sounds do.”

- “Culture arose from natural selection, and as culture gets under the skin and into the brain, it helps to shape the next generation of humans.”Connects with Omega Principle – Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century

- “We are performing a synchronized dance of prediction and action, regulating each other’s body budgets. This same synchrony is the basis of social connection and empathy; it makes people trust and like each other, and it’s crucial for parent-infant bonding.”

A New View of Human Nature

Sometimes, responsibility means that you’re the only one who can change things.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT – HOW EMOTIONS ARE MADE

- The Limits of Construction:

- “Your constructions aren’t arbitrary—your brain (and the mind it creates) must keep in touch with the bits of reality that count in order to keep your body alive and healthy.”

- “This variability is not infinite or arbitrary; it is constrained by the brain’s need for efficiency and speed, by the outside world.”

- “Construction cannot make a solid wall unsolid (unless you have mutant superpowers), but you can redraw countries, redefine marriage, and decide who’s worthwhile and who isn’t.”

- Your genes gave you a brain that can wire itself to its physical and social environment, and other members of your culture construct that environment with you. It takes more than one brain to create a mind.”

- “We are not blank slates, and our children are not “Silly Putty” to be shaped this way and that, but neither is biology destiny. When we peer into the workings of a functioning brain, we don’t see mental modules. We see core systems that interact continuously in complex ways to produce many sorts of minds, depending on culture.”

- “But the human brain has few preset mental concepts, such as perhaps pleasantness and unpleasantness (valence), agitation and calmness (arousal), loudness and softness, brightness and darkness, and other properties of consciousness. Instead, variation is the norm.”

- “We all walk a tightrope between the world and the mind, and between the natural and the social.”

- “Your brain can create more than one explanation for the sensory input around you—not an infinite number of realities, but definitely more than one.”

- “Construction agrees that you’re indeed the agent of your own destiny, but you are bounded by your surroundings.”

- Responsibility:

- “So “responsibility” means making deliberate choices to change your concepts.”

- “No particular conflict is predetermined by evolution. Conflicts persist due to social circumstances that wire the brains of the individuals who participate. Someone must take responsibility to change these circumstances and concepts. Who’s going to do it, if not the people themselves?”

- “If you grow up in a society full of anger or hate, you can’t be blamed for having the associated concepts, but as an adult, you can choose to educate yourself and learn additional concepts. It’s certainly not an easy task, but it is doable.”

- ““You are an architect of your experience.” You are indeed partly responsible for your actions, even so-called emotional reactions that you experience as out of your control. It is your responsibility to learn concepts that, through prediction, steer you away from harmful actions. You also bear some responsibility for others, because your actions shape other people’s concepts and behaviors, creating the environment that turns genes on and off to wire their brains, including the brains of the next generation.”

- “To be an effective architect of your experience, you need to distinguish physical reality from social reality, and never mistake one for the other, while still understanding that the two are irrevocably entwined.”

- “Social reality implies that we are all partly responsible for one another’s behavior, not in a fluffy, let’s-all-blame-society sort of way, but a very real brain-wiring way.”

- “Due to their trauma, their brains continue to model a hostile world, even after they’ve escaped to a better one.”

- “Sometimes, responsibility means that you’re the only one who can change things.”

- “In the classical view of emotion, the responsibility is all on the perceiver’s end because emotions are supposedly displayed universally. In a construction mindset, you also bear the responsibility to be a good sender.”

- “If your brain operates by prediction and construction and rewires itself through experience, then it’s no overstatement to say that if you change your current experiences today, you can change who you become tomorrow.”

- Essentialism:

- “The belief in essences is called essentialism. It presupposes that certain categories—sadness and fear, dogs and cats, African and European Americans, men and women, good and evil—each have a true reality or nature. Within each category, the members are thought to share a deep, underlying property (an essence) that causes them to be similar, even if they have some superficial differences.”

- “All versions of the classical view agree that each emotion category has a distinct fingerprint; they just disagree on the nature of the essences.”

- “People are almost always unaware that they essentialize; they fail to see their own hands in motion as they carve dividing lines in the natural world.”

- “The ideal dog doesn’t exist: it’s a statistical summary of many diverse dogs. No features are necessary, sufficient, or even typical of every individual in the population. This observation, known as population thinking, is central to Darwin’s theory of evolution.”

- Connects with Plato’s World of Forms.

- “Population thinking is based on variation, whereas essentialism is based on sameness.”

- “James actually wrote that each instance of emotion, not each category of emotion, comes from a unique bodily state.”

- “Millions of people around the world can instantly, effortlessly recognize Kermit the Frog, but that doesn’t mean the human brain is wired for Muppet recognition.”

- “Essentialism is also remarkably difficult to disprove. Since an essence can be an unobservable property, people are free to believe in essences even when they cannot be found.”

- “Essentialism inoculates itself against counterevidence.”

- “Casting away those essences remains a challenge today because the brain is wired to categorize, and categories breed essentialism.”

- “Firestein opens Ignorance with an old proverb, “It is very difficult to find a black cat in a dark room, especially when there is no cat.” This statement beautifully sums up the search for essences.”

- Behaviourism:

- “If we cannot measure emotions in the body and brain, they said, we’ll measure only what happens before and after: the events that bring on an emotion and the physical reactions that result. Never mind what’s happening inside that skull thing in the middle. Thus began the most notorious historical period in psychology, called behaviorism. Emotions were redefined as mere behaviors for survival: fighting, fleeing, feeding, and mating, collectively known as the “four F’s.””

- “As philosopher Thomas Kuhn wrote about the structure of scientific revolutions: “To reject one paradigm without simultaneously substituting another is to reject science itself.””

Mastering Your Emotions

The major ingredients in that recipe are your body budget and your concepts. If you maintain a balanced body budget, you’ll feel better in general, so that’s where we’ll start. And if you develop a rich set of concepts, you’ll have a toolbox for a meaningful life.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT – HOW EMOTIONS ARE MADE

- Can we change?

- “Change is not easy. Ask any therapist or Buddhist monk; they’ve trained for years to become aware of their experiences and control them.”

- “Can you snap your fingers and change your feelings at will, like changing your clothes? Not really. Even though you construct your emotional experiences, they can still bowl you over in the moment. However, you can take steps now to influence your future emotional experiences, to sculpt who you will be tomorrow.”

- The Self:

- “So in my view, the self is a plain, ordinary concept just like “Tree,” “Things That Protect You from Stinging Insects,” and “Fear.””

- “If the self is a concept, then you construct instances of your self by simulation.”

- “Social psychologists say that we have multiple selves, but you can think of this repertoire as instances of a single, goal-based concept called “The Self” in which the goal shifts based on context.”

- “So every categorization you construct—about objects in the world, other people, purely mental concepts like “Justice,” and so on—contains a little bit of you. This is the rudimentary mental basis of your sense of self.”

- “Deconstructing the self for a moment allows you to reduce the size of your affective niche so concepts like “Reputation,” “Power,” and “Wealth” become unnecessary.”

- “So, as a field, psychology keeps rediscovering the same phenomena and giving them new names and searching for them in new places in the brain. That’s why we have a hundred concepts for “the self.””

- “Ironically, each of us has a brain that creates a mind that misunderstands itself.”

Pillar 1: Balanced Body-Budget

- Eat healthfully.

- “The most basic thing you can do to master your emotions, in fact, is to keep your body budget in good shape.”

- “I apologize if I suddenly sound like your mother, but the road begins with eating healthfully, exercising, and getting enough sleep.”

- “The science is crystal clear on healthful food, regular exercise, and sleep as prerequisites for a balanced body budget and a healthy emotional life.’

- Move and exercise.

- “Moving your body can change your predictions and therefore your experience.”

- Yoga: “People who practice yoga long-term are able to calm down more quickly and effectively, probably due to some combination of physical activity and the slow-paced breathing.”

- “Take walks in a public garden or park.”

- Getting enough sleep.

- Get touched.

- “Human touch is good for your health—it improves your body budget by way of your interoceptive network. Massage is especially helpful after vigorous exercise. It limits inflammation and promotes faster healing of the tiny tears in muscle tissue that result from exercise, which you might otherwise experience as unpleasant.”

- Massage guns: Wattne W2 & Theragun Elite

- “Human touch is good for your health—it improves your body budget by way of your interoceptive network. Massage is especially helpful after vigorous exercise. It limits inflammation and promotes faster healing of the tiny tears in muscle tissue that result from exercise, which you might otherwise experience as unpleasant.”

- Design your environment.

- “Your physical surroundings also affect your body budget, so if possible, try to spend time in spaces with less noise and crowding, and more greenery and natural light.”

- “Another approach to mastering your emotions in the moment is to change your location or situation, which in turn can change your predictions.”

- Get lost in quality content.

- “Diving into a compelling novel is also healthful for your body budget. This is more than mere escapism; when you get involved in someone else’s story, you aren’t as involved in your own. Such mental excursions engage part of your interoceptive network, known as the default mode network, and keep you from ruminating (which would be bad for the budget). If you are not a reader, see a compelling film. If the story is sad, have a good cry, which is also beneficial to the budget.”

- Practice Gratitude.

- “Here’s another simple budget-booster: set up regular lunch dates with a friend and take turns treating each other. “

- “Research shows that giving and gratitude have mutual benefits for the body budgets involved, so when you take turns, you reap the benefits.”

- Keep track of positive experiences.

- Each time you attend to positive things, you tweak your conceptual system, reinforcing concepts about those positive events and making them salient in your mental model of the world.”

- “It’s even better if you write about your experiences because, again, words lead to concept development, which will help you predict new moments to cultivate positivity.”

- Avoid rumination.

- “Rumination is a vicious cycle: each time you dwell on (say) a recent breakup of a relationship, you add another instance to predict with, which expands your opportunity to ruminate.”

- “These concepts, as patterns of neural activity, get easier and easier for your brain to re-create, like well-trodden walking paths that grow deeper with each passerby’s footsteps.”

- “Every experience you construct is an investment, so invest wisely. Cultivate the experiences you want to construct again in the future.

- Connects with James Clear’s idea of voting for who you want to be.

“After attending to your body budget, the next best thing you can do for emotional health is to beef up your concepts, otherwise known as “becoming more emotionally intelligent.””

Pillar 2: Emotional Intelligence

- Refine your concepts. Increase emotional granularity.

- ““Happiness” and “Sadness” are each populations of diverse instances. Therefore, emotional intelligence (EI) is about getting your brain to construct the most useful instance of the most useful emotion concept in a given situation. (And also when not to construct emotions but instances of some other concept.)

- “You could predict and categorize your sensations more efficiently, and better tailor your actions to your environment.”

- “The third was to categorize sensations with greater granularity, such as: “In front of me is an ugly spider and it is disgusting, nerve-wracking, and yet, intriguing.” The third approach was the most effective in helping people with arachnophobia to be less anxious when observing a spider and to actually approach spiders. The effects lasted a week beyond the experiment, too.”

- Mood Meter app

- Acquire new concepts.

- “There are many ways to gain new concepts: taking trips (even just a walk in the woods), reading books, watching movies, trying unfamiliar foods. Be a collector of experiences. Try on new perspectives the way you try on new clothing.”

- Perhaps the easiest way to gain concepts is to learn new words.