Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD

Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MDMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Solid evidence-based book on longevity. That said, the first section on tactics/strategy and the last chapter on emotions were my personal favourite. This book has many pearls and will help me extend my lifespan and health span by a few years. However, I think the true value of this book lies in empowering the reader to think about and take their life seriously.

View all my reviews

TLDR – Main Takeaways

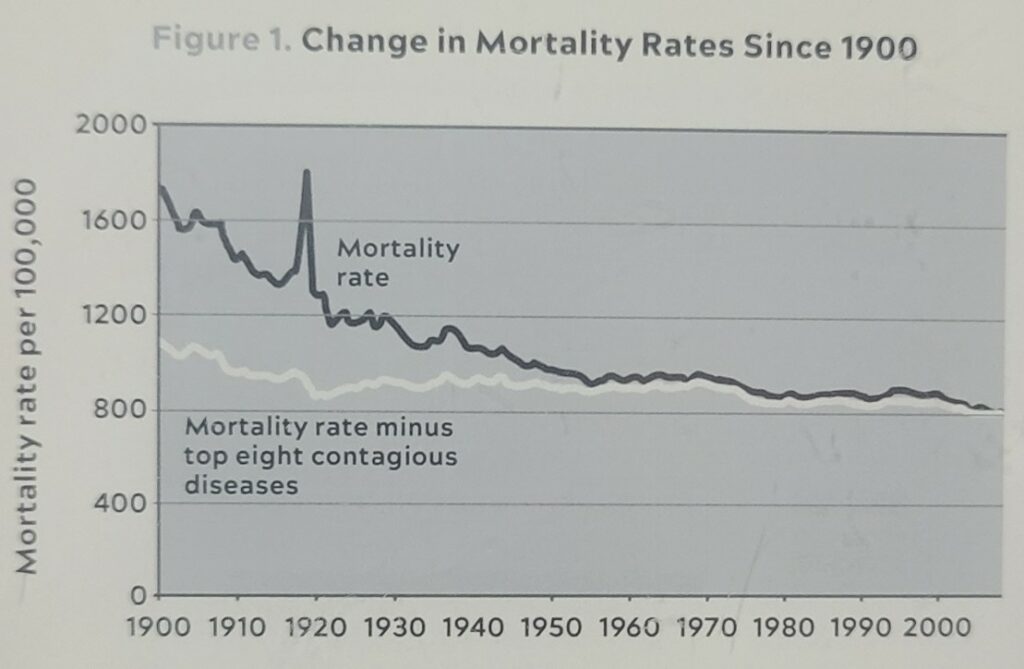

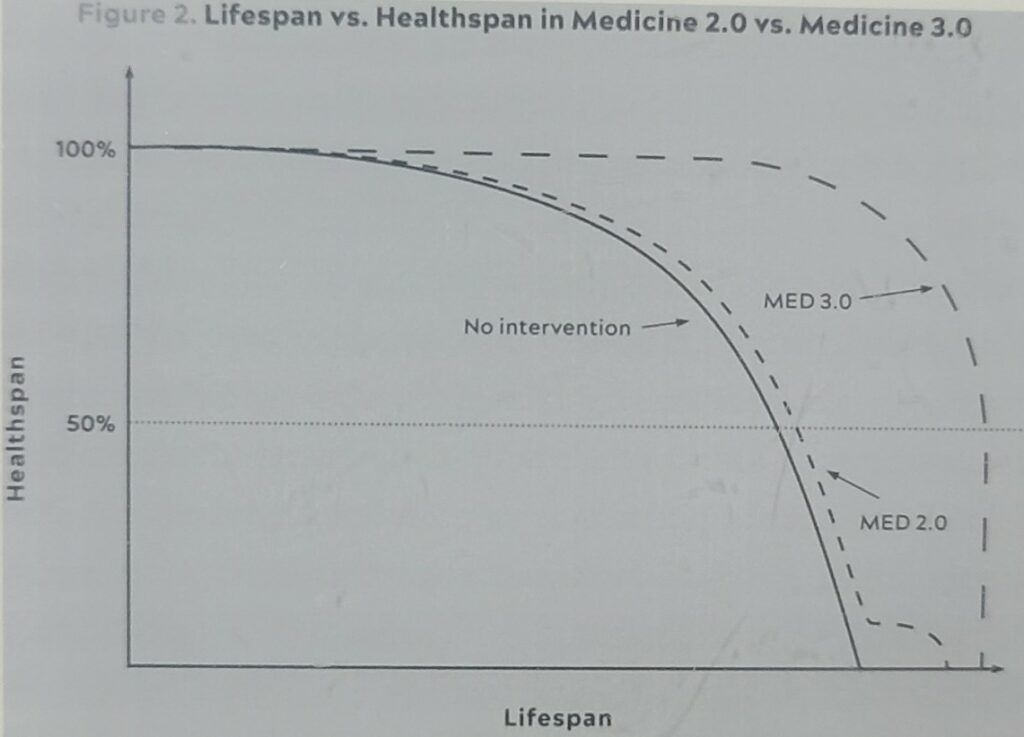

- Medicine 2.0 has made tremendous progress in limiting fast deaths, but relatively little in preventing slow deaths. We need Medicine 3.0 to extend healthspan until the very last drops of lifespan (see curves below).

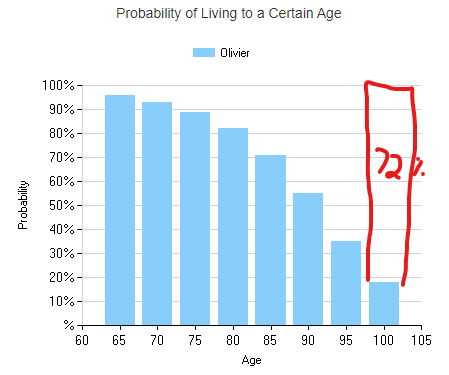

- Everybody should be training for the centenarian decathlon. Not only do we want to live to 100, but we need to be functional in our later years. We can reverse engineer the math to figure out how much we need to train to accomplish our goal.

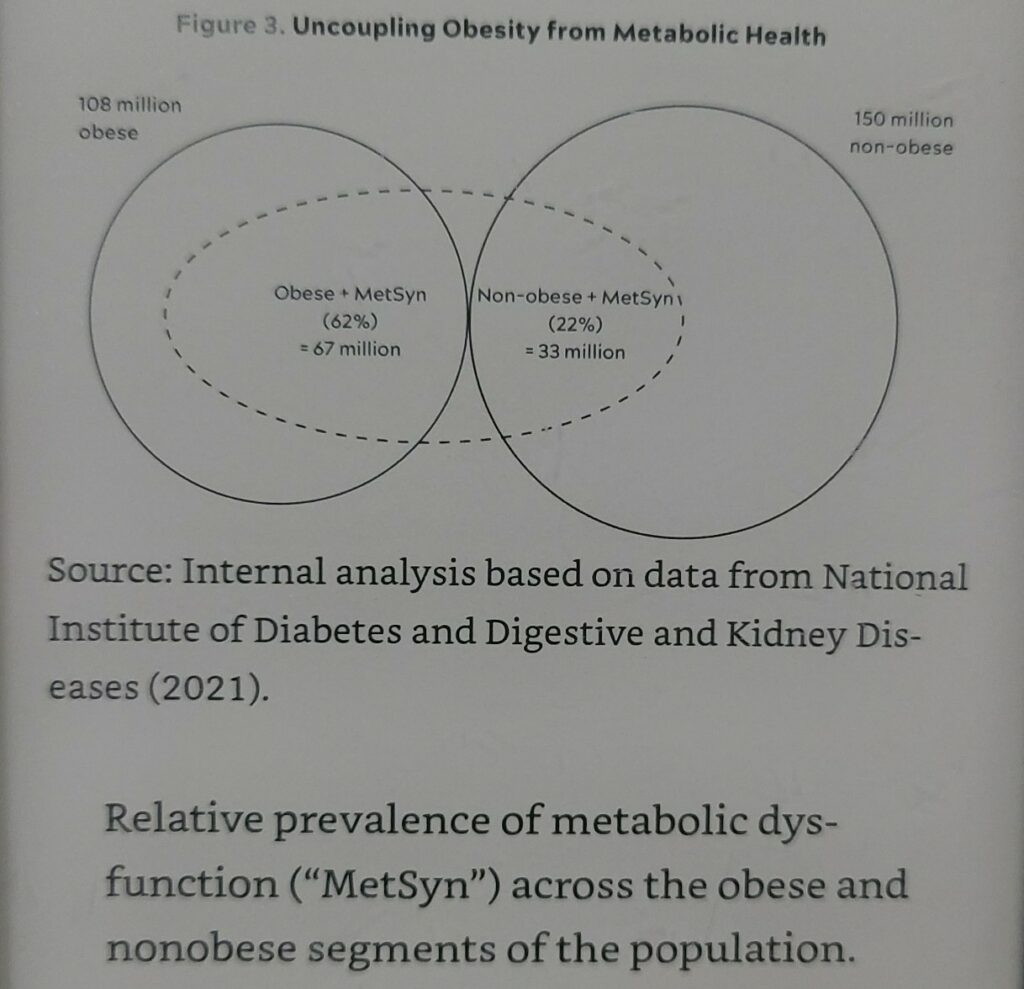

- Obesity is not a sufficient cause of metabolic syndrome (see chart below).

- Don’t wait to be diagnosed with a disease. Most if not all horsemen start many decades before symptoms appears. Now is the best time to start your prevention plan.

- “”Another way to think of all this is that someone might be considered “low risk” at a given point—but on what time horizon? The standard is ten years. But what if our time horizon is “the rest of your life”?””

- “Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” – Sun Tzu

- Exercise trumps every other intervention to extend lifespan. But more importantly, done properly, it certainly extends healthspan.

- Losing a couple of years of life at the tail end is a worthwhile tradeoff if your healthspan is extended by decades.

- Nutrition is tricky. Don’t get caught in the nitty-gritty in all the tactics and genes. Remember that the goal is the live a more fulfilling life for longer.

- “Why would you want to live longer if you’re so unhappy?” – Esther Perel

Book Notes & Highlights

Introduction

In short, it had finally dawned on me that the only way to solve the problem was not to get better at catching the eggs. Instead, we needed to try to stop the guy who was throwing them. We had to figure out how to get to the top of the building, find the guy, and take him out.

Peter Attia – Outlive

There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.

Bishop Desmond Tutu

Part I

Chapter 1 – The Long Game

The Chronology of Death

- “Later, as a surgical resident at Johns Hopkins, I would learn that death comes at two speeds: fast and slow.”

- “Medicine’s biggest failing is in attempting to treat all these conditions at the wrong end of the timescale—after they are entrenched—rather than before they take root.”

The Two Components of Longevity

- “I hope to convince you that with enough time and effort, you can potentially extend your lifespan by a decade and your healthspan possibly by two, meaning you might hope to function like someone twenty years younger than you.”

- “The other key point is that lifespan and healthspan are not independent variables; they are tightly intertwined.”

Chapter 2 – Medicine 3.0

The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining.

John F. Kennedy

When did Noah build the ark? Long before it began to rain.

Peter Attia – Outlive

Medicine 2.0 tries to figure out how to get dry after it starts raining. Medicine 3.0 studies meteorology and tries to determine whether we need to build a better roof, or a boat.

Peter Attia – Outlive

| Medicine 2.0 | Medicine 3.0 | |

| Emphasis | Treatment of symptoms | Proactive prevention of disease |

| Treats patients as | The average patient | A nuanced individual |

| Risk | Avoid at all costs | Assesses risk of action and non-action carefully |

| Focus | Extending lifespan | Extending healthspan |

| Patient is | Passive with no responsibility and agency | Active with responsibility and agency |

| Tactics | Procedures (surgery) and medications | Exercise, nutrition, sleep, emotional health, and exogenous molecules (drugs, hormones, supplements) |

First, Do No Harm

- “The trouble began with Hippocrates. Most people are familiar with the ancient Greek’s famous dictum: “First, do no harm.” It succinctly states the physician’s primary responsibility, which is to not kill our patients or do anything that might make their condition worse instead of better. Makes sense. There are only three problems with this: (a) Hippocrates never actually said these words,[*1] (b) it’s sanctimonious bullshit, and (c) it’s unhelpful on multiple levels.”

- “What bothers me most about “First, do no harm,” though, is its implication that the best treatment option is always the one with the least immediate downside risk—and, very often, doing nothing at all. Every doctor worth their diploma has a story to disprove this nonsense.”

- “My point is that a physician who has never done any harm, or at least confronted the risk of harm, has probably never done much of anything to help a patient either. And as in the case of my teenage stabbing victim, sometimes doing nothing is the riskiest choice of all.”

The Financial Case for Medicine 3.0

- “There are few insurance reimbursement codes for most of the largely preventive interventions that I believe are necessary to extend lifespan and healthspan. Health insurance companies won’t pay a doctor very much to tell a patient to change the way he eats, or to monitor his blood glucose levels in order to help prevent him from developing type 2 diabetes. Yet insurance will pay for this same patient’s (very expensive) insulin after he has been diagnosed.”

- “Nearly all the money flows to treatment rather than prevention—and when I say “prevention,” I mean prevention of human suffering.”

- “Continuing to ignore healthspan, as we’ve been doing, not only condemns people to a sick and miserable older age but is guaranteed to bankrupt us eventually.”

Chapter 3 – Objective, Strategy, Tactics

Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.

Sun Tzu

Our Objective

- “To delay death, and to get the most out of our extra years.”

- “We want to delay or prevent these conditions so that we can live longer without disease, rather than lingering with disease.”

Strategy versus Tactic

- “To achieve our objectives, we first need to have a strategy: an overall approach, a conceptual scaffolding or mental model that is informed by science, is tailored to our goals, and gives us options. Our specific tactics flow from our strategy, and the strategy derives from our objective.”

- “The point is that the tactics are what you do when you are actually in the ring. The strategy is the harder part, because it requires careful study of one’s opponent, identifying his strengths and weaknesses, and figuring out how to use both to your advantage, well before actually stepping in the ring.”

- “Of course, not every problem you face requires a strategy. In fact, many don’t. You don’t need a strategy if your objective is, say, to avoid getting a sunburn.”

- “Without an understanding of the strategy, and the science that informs it, our tactics will not mean much, and you’ll forever ride the merry-go-round of fad diets and trendy workouts and miracle supplements.”

- “A good strategy allows us to adopt new tactics and discard old ones in service of our objectives.”

- “In a sense it’s a bit like charting an investment strategy: we are seeking the tactics that are likeliest, based on what we know now, to deliver a better-than-average return on our capital, while operating within our own individual tolerance for risk.”

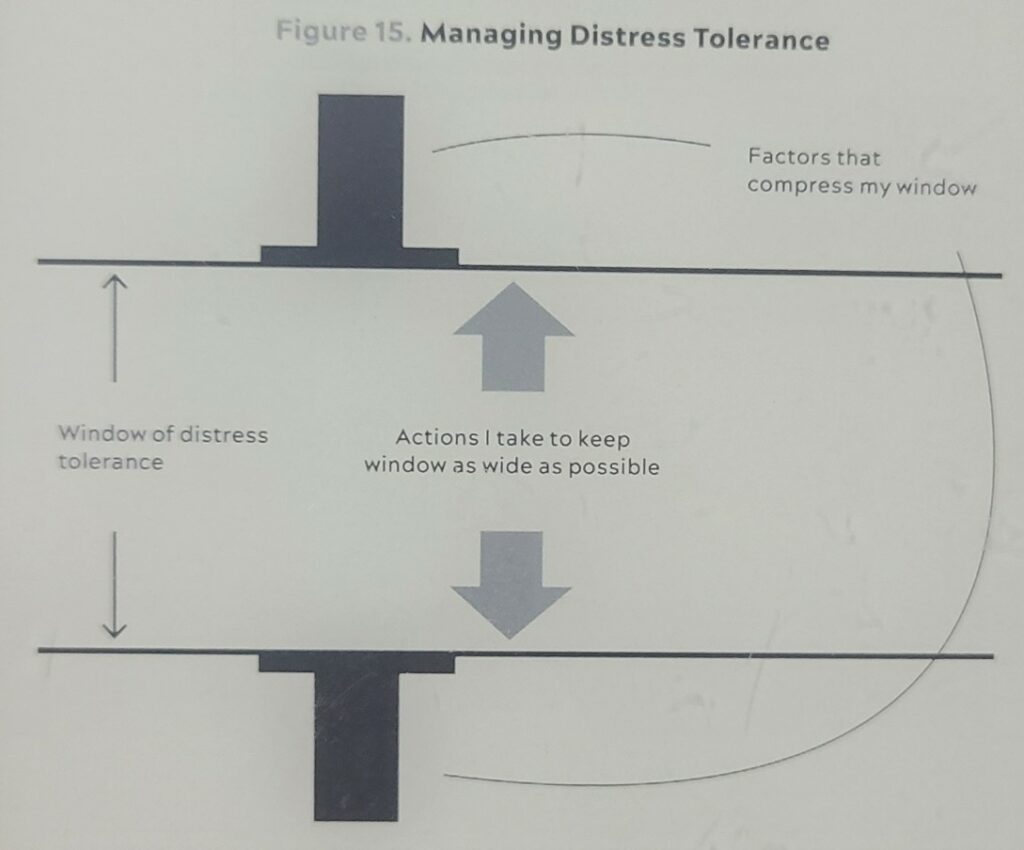

The Healthspan 3D Space

- “I think about healthspan and its deterioration in terms of three categories, or vectors. The first vector of deterioration is cognitive decline. … The second vector of deterioration is the decline and eventual loss of function of our physical body. … The third and final category of deterioration, I believe, has to do with emotional health. Unlike the others, this one is largely independent of age…”

- “Why would you want to live longer if you’re so unhappy?” – Esther Perel

The Weakness of Evidence-based Medicine

- “These trials take heterogeneous inputs (the people in the study or studies) and come up with homogeneous results (the average result across all those people). Evidence-based medicine then insists that we apply those average findings back to individuals. The problem is that no patient is strictly average.”

- Waiting for perfect studies (which are sometimes impossible to conduct with humans) puts us at risk of the harm of doing nothing.

Evidence-informed, Risk-adjusted Precision Medicine

- “The purists of evidence-based medicine demand data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) before doing anything.”

- “The best we can hope for is reducing our uncertainty. A good experiment in biology only increases or decreases our confidence in the probability that our hypothesis is true or false.”

- “Our Option B strategy is based on combining insights from five different sources of data that, viewed separately, probably aren’t strong enough to act on. When taken together, however, they can provide a solid foundation for our tactics. But our supporting framework must shift, from exclusively evidence-based to evidence-informed, risk-adjusted precision medicine.”

- Centenarian Studies

- Limitation: “Observational rather than experimental, so we can’t truly infer cause and effect.”

- Animal “Models”

- “My rule of thumb is that if a given intervention can be shown to extend lifespan or healthspan in multiple species spanning a billion years of evolution, for example, from worms to monkeys, then I am inclined to take it seriously.”

- Human Studies of the Horsemen.

- Molecular & Mechanistic Insights

- Mendelian Randomization (MR for short)

- MR helps bridge the gap between randomized controlled trials, which can establish causality, and pure epidemiology, which often cannot.”

- “It accomplishes this by letting nature do the randomization.[*2] By considering the random variation in relevant genes and comparing them against the observed results, it eliminates many of the biases and confounders that limit the usefulness of pure epidemiology.”

Our Strategy

- “I used to prioritize nutrition over everything else, but I now consider exercise to be the most potent longevity “drug” in our arsenal, in terms of lifespan and healthspan. The data are unambiguous: exercise not only delays actual death but also prevents both cognitive and physical decline, better than any other intervention.”

- “The best science out there says that what you eat matters, but the first-order term is how much you eat: how many calories you take into your body.”

- “On Wall Street, gaining an advantage like this is called alpha, and we’re going to borrow the idea and apply it to health. I propose that with some unorthodox but very reasonable lifestyle changes, you can minimize the most serious threats to your lifespan and healthspan and achieve your own measure of longevity alpha.”

Part II

Chapter 4 – Centenarians

Centenarians

- “More broadly, it’s worth asking: What do healthy centenarians actually have in common? And, more importantly, what can we learn from them—if anything? Do they really live longer because of their idiosyncratic behaviors, like drinking whiskey, or despite them? Is there some other common factor that explains their extreme longevity, or is it simply luck?”

- “Centenarians are no more health-conscious than the rest of us. They may actually be worse.”

The Death Lottery

- There’s always a chance of dying at any moment. Are centenarians simply the ones getting lucky and escaping death every year, like the monkey flipping 100 heads in a row?

- “The overall mortality rate for Americans ages 100 and older is a staggering 36 percent, meaning that if Grandma is 101, she has about a one-in-three chance of dying in the next twelve months.”

The Genetic Lottery

While your genome is immutable, at least for the near future, gene expression can be influenced by your environment and your behaviors.

Peter Attia – Outlive

- “Broader genetic studies suggest that hundreds, if not thousands, of genes could be involved, each making its own small contribution—and that there is no such thing as a “perfect” centenarian genome.”

- “Thus it appears that no two centenarians follow the exact same genetic path to reaching extreme old age. There are many ways to achieve longevity; not just one or two.”

- “Studies of Scandinavian twins have found that genes may be responsible for only about 20 to 30 percent of the overall variation in human lifespan. The catch is that the older you get, the more genes start to matter.”

- “These individuals appeared to have very little in common with one another genetically. And their longevity may be due to dumb luck after all.”

- “One of the most potent individual genes yet discovered is related to cholesterol metabolism, glucose metabolism—and Alzheimer’s disease risk. You may have heard of this gene, which is called APOE, because of its known effect on Alzheimer’s disease risk.”

- “The e2 variant of APOE, on the other hand, seems to protect its carriers against dementia—and it also turns out to be very highly associated with longevity.”

- “Researchers have identified two other cholesterol-related genes, known as CETP and APOC3, that are also correlated with extreme longevity (and may explain why centenarians rarely die from heart disease).”

- “These are variants in a particular gene called FOXO3 that seem to be directly relevant to human longevity.”

- “Here’s where we start to see some hope, because FOXO3 can be activated or suppressed by our own behaviors. For example, when we are slightly deprived of nutrients, or when we are exercising, FOXO3 tends to be more activated, which is what we want.”

Genetactics

- “Can we, through our behaviors, somehow reap the same benefits that centenarians get for “free” via their genes? Or to put it more technically, can we mimic the centenarians’ phenotype, the physical traits that enable them to resist disease and survive for so long, even if we lack their genotype? Is it possible to outlive our own life expectancy if we are smart and strategic and deliberate about it? If the answer to this question is yes, as I believe it is, then understanding the inner workings of these actuarial lottery winners—how they achieve their extreme longevity—is a worthwhile endeavor that can inform our strategy.”

- “Put another way, if we want to outlive our life expectancy and live better longer, we will have to work hard to earn it—through small, incremental changes.”

- “Curiously, despite the fact that female centenarians outnumber males by at least four to one, the men generally scored higher on both cognitive and functional tests.”

Chapter 5 – Eat Less, Live Longer?

Longevity Drugs

- “But rapamycin turned out to be so much more than the next Dr. Scholl’s foot spray. It proved to have powerful effects on the immune system, and in 1999 it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help transplant patients accept their new organs.”

- “The reason rapamycin has so many diverse applications is thanks to a property that Sehgal had observed, but never explored, which is that it tends to slow down the process of cellular growth and division.”

- “Why do we care about mTOR? Because this mechanism turns out to be one of the most important mediators of longevity at the cellular level. Not only that, but it is highly “conserved,” meaning it is found in virtually all forms of life, ranging from yeast to flies to worms and right on up to us humans. In biology, “conserved” means that something has been passed on via natural selection, across multiple species and classes of organisms—a sign that evolution has deemed it to be very important.”

- “Kaeberlein has also observed that rapamycin seems to reduce systemic inflammation, perhaps by tamping down the activity of so-called senescent cells, which are “older” cells that have stopped dividing but have not died; these cells secrete a toxic cocktail of inflammatory cytokines, chemicals that can harm surrounding cells. Rapamycin seems to reduce these inflammatory cytokines.”

- “Even though the drug had been given late in life, when the mice were already “old” (six hundred days, roughly the equivalent of humans in their sixties), it had still boosted the animals’ remaining life expectancy by 28 percent for males and 38 percent for females. It was the equivalent of a pill that could make a sixty-year-old woman live to the age of ninety-five.”

- “The real headline here, however, was that no other molecule had been shown to extend lifespan in a mammal. Ever.“

- Nicotinamide riboside (NR) & Resveratrol did not have robust effects on lifespan.

- “Of course, there are no data showing that any of these supplements lengthen life or improve health in humans.”

- “This study suggested that rapamycin (and its derivatives) might actually be more of an immune modulator than an “immunosuppressor,” as it had almost always been described before this study: that is, under some dosing regimens it can enhance immunity, while under completely different dosing regimens it may inhibit immunity.”

- “Giving the drug daily, as is typically done with transplant patients, appears to inhibit both complexes, while dosing the drug briefly or cyclically inhibits mainly mTORC1, unlocking its longevity-related benefits, with fewer unwanted side effects.”

- “A small but growing number of people, including me and a handful of my patients, already take rapamycin off-label for its potential geroprotective benefits. I can’t speak for everyone, but taking it cyclically does appear to reduce unwanted side effects, in my experience.”

- “Over time, researchers noticed (and studies appeared to confirm) that patients on metformin appeared to have a lower incidence of cancer than the general population. One large 2014 analysis seemed to show that diabetics on metformin actually lived longer than nondiabetics, which is striking. But none of these observations “prove” that metformin is geroprotective—hence the need for a clinical trial.”

Caloric Restriction (CR)

- “CR seems to improve their healthspan in addition to their lifespan. You’d think that hunger might be unhealthy, but the scientists have actually found that the less they feed the animals, the longer they live. Its effects seem to be dose dependent, up to a point, almost like a drug.”

- “Reducing the amount of nutrients available to a cell seems to trigger a group of innate pathways that enhance the cell’s stress resistance and metabolic efficiency—all of them related, in some way, to mTOR.”

- “Specifically, it seems to be a drop in amino acids that induces mTOR to shut down, and with it all the anabolic (growth) processes that mTOR controls. Instead of making new proteins and undergoing cell division, the cell goes into a more fuel-efficient and stress-resistant mode, activating an important cellular recycling process called autophagy, which means “self-eating” (or better yet, “self-devouring”).”

- “Impaired autophagy is thought to be an important driver of numerous aging-related phenotypes and ailments, such as neurodegeneration and osteoarthritis. Thus, I find it fascinating that this very important cellular mechanism can be triggered by certain kinds of interventions, such as a temporary reduction in nutrients (as when we are exercising or fasting)—and the drug rapamycin.”

- “For one, CR’s usefulness remains doubtful outside of the lab; very lean animals may be more susceptible to death from infection or cold temperatures. And while eating a bit less worked for Luigi Cornaro, as well as for some of my own patients, long-term severe caloric restriction is difficult if not impossible for most humans to sustain. Furthermore, there is no evidence that extreme CR would truly maximize the longevity function in an organism as complex as we humans, who live in a more variable environment than the animals described above. While it seems likely that it would reduce the risk of succumbing to at least some of the Horsemen, it seems equally likely that the uptick in mortality due to infections, trauma, and frailty might offset those gains.”

Chapter 6 – The Crisis of Abundance

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

- “More than one in four people on this planet have some degree of NASH or its precursor, known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, which is what we had observed in our patient that day in the operating room.”

- “NAFLD is highly correlated with both obesity and hyperlipidemia (excessive cholesterol), yet it often flies under the radar, especially in its early stages.”

- NAFLD ==> NASH ==> Type 2 Diabetes

- “NAFLD and NASH are basically two stages of the same disease. NAFLD is the first stage, caused by (in short) more fat entering the liver or being produced there than exiting it. The next step down the metabolic gangplank is NASH, which is basically NAFLD plus inflammation, similar to hepatitis but without a viral infection.”

- “Type 2 diabetes is technically a distinct disease, defined very clearly by glucose metrics, but I view it as simply the last stop on a railway line passing through several other stations, including hyperinsulinemia, prediabetes, and NAFLD/NASH. If you find yourself anywhere on this train line, even in the early stages of NAFLD, you are likely also en route to one or more of the other three Horsemen diseases (cardiovascular disease, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease).”

- “Both NAFLD and NASH are still reversible.”

- “The liver is a highly resilient organ, almost miraculously so. It may be the most regenerative organ in the human body. When a healthy person donates a portion of their liver, both donor and recipient end up with an almost full-sized, fully functional liver within about eight weeks of the surgery, and the majority of that growth takes place in just the first two weeks.”

“Nature is quite happy for us to be fat and frankly doesn’t care if we get diabetes.”

PETER ATTIA – OUTLIVE

Obesity

- “In the late 1970s, the average American adult male weighed 173 pounds. Now the average American man tips the scale at nearly 200 pounds. In the 1970s, a 200-pound man would have been considered very overweight; today he is merely average. So you can see how in the twenty-first century, “average” is not necessarily optimal.”

- “Obesity is merely one symptom of an underlying metabolic derangement, such as hyperinsulinemia, that also happens to cause us to gain weight.”

- “But not everyone who is obese is metabolically unhealthy, and not everyone who is metabolically unhealthy is obese.”

- “Studies have found that approximately one-third of those folks who are obese by BMI are actually metabolically healthy, by many of the same parameters used to define the metabolic syndrome (blood pressure, triglycerides, cholesterol, and fasting glucose, among others). At the same time, some studies have found that between 20 and 40 percent of nonobese adults may be metabolically unhealthy, by those same measures.”

Metabolic Syndrome

- “Today we call this cluster of problems “metabolic syndrome” (or MetSyn), and it is defined in terms of the following five criteria:

- High blood pressure (>130/85)

- High triglycerides (>150 mg/dL)

- Low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL in men or <50 mg/dL in women)

- Central adiposity (waist circumference >40 inches in men or >35 in women)

- Elevated fasting glucose (>110 mg/dL)

- If you meet three or more of these criteria, then you have the metabolic syndrome.”

- “Metabolism is the process by which we take in nutrients and break them down for use in the body.”

- “One reason I find value in the concept of metabolic syndrome is that it helps us see these disorders as part of a continuum and not a single, binary condition. Its five relatively simple criteria are useful for predicting risk at the population level.”

- “In my patients, I monitor several biomarkers related to metabolism, keeping a watchful eye for things like elevated uric acid, elevated homocysteine, chronic inflammation, and even mildly elevated ALT liver enzymes. Lipoproteins, which we will discuss in detail in the next chapter, are also important, especially triglycerides; I watch the ratio of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol (it should be less than 2:1 or better yet, less than 1:1), as well as levels of VLDL, a lipoprotein that carries triglycerides—all of which may show up many years before a patient would meet the textbook definition of metabolic syndrome.”

- “But the first thing I look for, the canary in the coal mine of metabolic disorder, is elevated insulin.”

Safe Energy Storage

- “Consider that five grams of glucose, spread out across one’s entire circulatory system, is normal, while seven grams—a teaspoon and a half—means you have diabetes. As I said, the liver is an amazing organ.”

- “Even a relatively lean adult may carry ten kilograms of fat in their body, representing a whopping ninety thousand calories of stored energy.”

- “The twist here is that fat—that is, subcutaneous fat, the layer of fat just beneath our skin—is actually the safest place to store excess energy. Fat in and of itself is not bad. It’s where we should put surplus calories. That’s how we evolved.”

- “This fat flux goes on continually, and as long as you haven’t exceeded your own fat storage capacity, things are pretty much fine.”

- “As more calories flood into your subcutaneous fat tissue, it eventually reaches capacity and the surplus begins spilling over into other areas of your body: into your blood, as excess triglycerides; into your liver, contributing to NAFLD; into your muscle tissue, contributing directly to insulin resistance in the muscle (as we’ll see); and even around your heart and your pancreas (figure 4). None of these, obviously, are ideal places for fat to collect; NAFLD is just one of many undesirable consequences of this fat spillover.”

- “All other things being equal, someone who carries a bit of body fat may also have greater fat-storage capacity, and thus more metabolic leeway than someone who appears to be more lean.”

- “This is why I insist my patients undergo a DEXA scan annually—and I am far more interested in their visceral fat than their total body fat.”

Insulin Resistance

- “Insulin resistance is a term that we hear a lot, but what does it really mean? Technically, it means that cells, initially muscle cells, have stopped listening to insulin’s signals, but another way to visualize it is to imagine the cell as a balloon being blown up with air. Eventually, the balloon expands to the point where it gets more difficult to force more air inside. You have to blow harder and harder. This is where insulin comes in, to help facilitate the process of blowing air into the balloon. The pancreas begins to secrete even more insulin, to try to remove excess glucose from the bloodstream and cram it into cells. For the time being it works, and blood glucose levels remain normal, but eventually you reach a limit where the “balloon” (cells) cannot accept any more “air” (glucose).”

- “Insulin is all about fat storage, not fat utilization.”

- “In 1940 the famed diabetologist Elliott Joslin estimated that about one person in every three to four hundred was diabetic, representing an enormous increase from just a few decades earlier, but it was still relatively uncommon. By 1970, around the time I was born, its prevalence was up to one in every fifty people. Today over 11 percent of the US adult population, one in nine, has clinical type 2 diabetes, according to a 2022 CDC report, including more than 29 percent of adults over age sixty-five. Another 38 percent of US adults—more than one in three—meet at least one of the criteria for prediabetes. That means that nearly half of the population is either on the road to type 2 diabetes or already there.”

- “But the first thing I look for, the canary in the coal mine of metabolic disorder, is elevated insulin.”

- “One test that I like to give patients is the oral glucose tolerance test, or OGTT, where the patient swallows ten ounces of a sickly-sweet, almost undrinkable beverage called Glucola that contains seventy-five grams of pure glucose, or about twice as much sugar as in a regular Coca-Cola.[*6] We then measure the patient’s glucose and their insulin, every thirty minutes over the next two hours.”

- “But the insulin in someone at the early stages of insulin resistance will rise very dramatically in the first thirty minutes and then remain elevated, or even rise further, over the next hour. This postprandial insulin spike is one of the biggest early warning signs that all is not well.”

- “Studies have found that insulin resistance itself is associated with huge increases in one’s risk of cancer (up to twelvefold), Alzheimer’s disease (fivefold), and death from cardiovascular disease (almost sixfold)—all of which underscores why addressing, and ideally preventing, metabolic dysfunction is a cornerstone of my approach to longevity.”

Fructose

- “But as it turns out, we humans have a unique capacity for turning calories from fructose into fat.”

- “At some point, our primate ancestors underwent a random genetic mutation that effectively switched on their ability to turn fructose into fat: the gene for the uricase enzyme was “silenced,” or lost. Now, when these apes consumed fructose, they generated lots of uric acid, which caused them to store many more of those fructose calories as fat.”

- “Whatever form it takes, fructose does not pose a problem when consumed the way that our ancestors did, before sugar became a ubiquitous commodity: mostly in the form of actual fruit. It is very difficult to get fat from eating too many apples, for example, because the fructose in the apple enters our system relatively slowly, mixed with fiber and water, and our gut and our metabolism can handle it normally.”

- “I test my patients’ levels of uric acid, not only because high levels may promote fat storage but also because it is linked to high blood pressure. High uric acid is an early warning sign that we need to address a patient’s metabolic health, their diet, or both.”

- “I’ve seen patients work themselves into NAFLD by drinking too many “healthy” fruit smoothies, for the same reason: they are taking in too much fructose, too quickly.”

- “While it may be in vogue to vilify high-fructose corn syrup, which is 55 percent fructose and 45 percent glucose, it’s worth pointing out that good old table sugar (sucrose) is about the same, consisting of 50 percent fructose and 50 percent glucose. So there’s really not much of a difference between the two.”

Chapter 7 – The Ticker

Mechanics of Heart Disease

- “Globally, heart disease and stroke (or cerebrovascular disease), which I lump together under the single heading of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, or ASCVD, represent the leading cause of death, killing an estimated 2,300 people every day in the United States, according to the CDC—more than any other cause, including cancer.”

- “While heart disease is the most prevalent age-related condition, it is also more easily prevented than either cancer or Alzheimer’s disease.”

- “I’ll never forget the one-question pop quiz that Allan Sniderman dropped on me over dinner at Dulles Airport, back in 2014: “What proportion of heart attacks occur in people younger than age sixty-five?” I guessed high, one in four, but I was way low. Fully half of all major adverse cardiovascular events in men (and a third of those in women), such as heart attack, stroke, or any procedure involving a stent or a graft, occur before the age of sixty-five. In men, one-quarter of all events occur before age fifty-four.”

- “It is not an accident that the two biggest risk factors for heart disease, smoking and high blood pressure, cause damage to the endothelium. Smoking damages it chemically, while high blood pressure does so mechanically, but the end result is endothelial harm that, in turn, leads to greater retention of LDL.”

- “If the plaque does become unstable, eroding or even rupturing, you’ve really got problems. The damaged plaque may ultimately cause the formation of a clot, which can narrow and ultimately block the lumen of the blood vessel—or worse, break free and cause a heart attack or stroke. This is why we worry more about the noncalcified plaques than the calcified ones. Normally, however, most atherosclerotic plaques are fairly undramatic.”

Cholesterol

- “The reason they’re called high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL, respectively) has to do with the amount of fat relative to protein that each one carries. LDLs carry more lipids, while HDLs carry more protein in relation to fat, and are therefore more dense.”

- “Eating lots of saturated fat can increase levels of atherosclerosis-causing lipoproteins in blood, but most of the actual cholesterol that we consume in our food ends up being excreted out our backsides. The vast majority of the cholesterol in our circulation is actually produced by our own cells.”

- ““There’s no connection whatsoever between cholesterol in food and cholesterol in blood,” Keys said in a 1997 interview. “None. And we’ve known that all along. Cholesterol in the diet doesn’t matter at all unless you happen to be a chicken or a rabbit.” It took nearly two more decades before the advisory committee responsible for the US government dietary guidelines finally conceded (in 2015) that “cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” Glad we settled that.”

- “Newer research suggests that HDL has multiple other atheroprotective functions that include helping maintain the integrity of the endothelium, lowering inflammation, and neutralizing or stopping the oxidation of LDL, like a kind of arterial antioxidant.”

- “The cholesterol content in your LDL particles, your “bad” cholesterol number (technically expressed as LDL-C),[*3] is actually a decent if imperfect proxy for its biologic impact; lots of studies have shown a strong correlation between LDL-C and event risk. But the all-important “good cholesterol” number on your blood test, your HDL-C, doesn’t actually tell me very much if anything about your overall risk profile. Risk does seem to decline as HDL-C rises to around the 80th percentile. But simply raising HDL cholesterol concentrations by brute force, with specialized drugs, has not been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk at all.”

- “Atherosclerosis probably would not occur [emphasis mine] in the absence of LDL-C concentrations in excess of physiological needs (on the order of 10 to 20 mg/dL).””

- “And lo and behold, it turns out that low LDL cholesterol does not cause cancer or increase its risk. If we use the same technique to look at the effect of LDL levels on cardiovascular disease (our dependent variable), it turns out that higher LDL cholesterol is causally linked to the development of cardiovascular disease (as we’ll discuss in chapter 7).”

apoB

- “I’ve been saying LDL, but the key factor here is actually exposure to apoB-tagged particles, over time.”

- “So to gauge the true extent of your risk, we have to know how many of these apoB particles are circulating in your bloodstream. That number is much more relevant than the total quantity of cholesterol that these particles are carrying.”

- “evidence has piled up pointing to apoB as far more predictive of cardiovascular disease than simply LDL-C, the standard “bad cholesterol” measure. According to an analysis published in JAMA Cardiology in 2021, each standard-deviation increase in apoB raises the risk of myocardial infarction by 38 percent in patients without a history of cardiac events or a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (i.e., primary prevention). That’s a powerful correlation.”

- “I have all my patients tested for apoB regularly, and you should ask for the same test the next time you see your doctor. (Don’t be waved off by nonsensical arguments about “cost”: It’s about twenty to thirty dollars.)”

- “As we’ll discuss in the final section, I take a very hard line on lowering apoB, the particle that causes all this trouble. (In short: get it as low as possible, as early as possible.)”

- “In my clinical experience, about a third to half of people who consume high amounts of saturated fats (which sometimes goes hand in hand with a ketogenic diet) will experience a dramatic increase in apoB particles, which we obviously don’t want.[*8] Monounsaturated fats, found in high quantities in extra virgin olive oil, macadamia nuts, and avocados (among other foods), do not have this effect, so I tend to push my patients to consume more of these, up to about 60 percent of total fat intake. The point is not necessarily to limit fat overall but to shift to fats that promote a better lipid profile.”

Lp(a)

- “But because Lp(a) is a member of the apoB particle family, it also has the potential to penetrate the endothelium and get lodged in an artery wall; because of its structure, Lp(a) may be even more likely than a normal LDL particle to get stuck, with its extra cargo of lipids gone bad. Even worse, once in there, it acts partly as a thrombotic or proclotting factor, which helps to speed the formation of arterial plaques.”

- “This is why, if you have a history of premature heart attacks in your family, you should definitely ask for an Lp(a) test. We test every single patient for Lp(a) during their first blood draw. Because elevated Lp(a) is largely genetic, the test need only be done once (and cardiovascular disease guidelines are beginning to advise a once-a-lifetime test for it anyway).”

- “There was no quick fix for Anahad, or anyone else with elevated Lp(a). It does not seem to respond to behavioral interventions such as exercise and dietary changes the way that, say, LDL-C does. A class of drug called PCSK9 inhibitors, aimed at lowering apoB concentrations, does seem to be able to reduce Lp(a) levels by approximately 30 percent, but as yet there are no data suggesting that they reduce the excess events (heart attacks) attributable to that particle. Thus, the only real treatment for elevated Lp(a) right now is aggressive management of apoB overall.”

- “Simply put, I think you can’t lower apoB and LDL-C too much, provided there are no side effects from treatment. You want it as low as possible.”

- “Once you understand that apoB particles—LDL, VLDL, Lp(a)—are causally linked to ASCVD, the game completely changes. The only way to stop the disease is to remove the cause, and the best time to do that is now.”

Statins

- “But for many patients, if not for most, lowering apoB to the levels we aim for—the physiologic levels found in children—cannot be accomplished with diet alone, so we need to use nutritional interventions in tandem with drugs.”

- “Statins are far and away the most prescribed class of drugs for lipid management, but there are several other options that might be right for a given individual, and often we need to combine classes of drugs, so it’s not uncommon for a patient to take two lipid-lowering drugs that operate via distinct mechanisms.”

- “These are typically thought of as “cholesterol-lowering” medications, but I think we are better served to think about them in terms of increasing apoB clearance, enhancing the body’s ability to get apoBs out of circulation.”

- “For every seven people who are put on a statin at this early stage, we could potentially save one life. The reason for this is simple math: risk is proportional to apoB exposure over time.”

- “While there are seven statins on the market, I tend to start with rosuvastatin (Crestor) and only pivot from that if there is some negative effect from the drug (e.g., a symptom or biomarker).”

- “For people who can’t tolerate statins, I like to use a newer drug, called bempedoic acid (Nexletol), which manipulates a different pathway to accomplish much the same end..”

- “Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (Vascepa), a drug derived from fish oil and consisting of four grams of pharmaceutical-grade eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), also has FDA approval to reduce LDL in patients with elevated triglycerides.”

Time Horizon

- “Atherosclerosis is with us, in some form, throughout our life course. Yet most doctors consider it “overtreatment” to intervene if a patient’s computed ten-year risk of a major adverse cardiac event (e.g., heart attack or stroke) is below 5 percent, arguing that the benefits are not greater than the risks, or that treatment costs too much. In my opinion, this betrays a broader ignorance about the inexorable, long-term unfolding of heart disease. Ten years is far too short a time horizon. If we want to reduce deaths from cardiovascular disease, we need to begin thinking about prevention in people in their forties and even thirties.”

- “Another way to think of all this is that someone might be considered “low risk” at a given point—but on what time horizon? The standard is ten years. But what if our time horizon is “the rest of your life”?”

- “Yet most physicians and cardiology experts would still insist that one’s thirties are too young to begin to focus on primary prevention of cardiac disease. This viewpoint is directly challenged by a 2018 JAMA Cardiology paper coauthored by Allan Sniderman, comparing ten-year versus thirty-year risk horizons in terms of prevention. Sniderman and colleagues’ analysis found that looking at a thirty-year time frame rather than the standard ten years and taking aggressive precautionary measures early—like beginning statin treatment earlier in certain patients—could prevent hundreds of thousands more cardiac events, and by implication could save many lives.”

- “We know that smoking is causally linked to lung cancer. Should we tell someone to stop smoking only after their ten-year risk of lung cancer reaches a certain threshold?”

Chapter 8 – The Runaway Cell

If the first rule of cancer is “Don’t get cancer,” the second rule is “Catch it as soon as possible.”

Peter Attia – Outlive

What is Cancer?

- “Contrary to popular belief, cancer cells don’t grow faster than their noncancerous counterparts; they just don’t stop growing when they are supposed to.”

- “The second property that defines cancer cells is their ability to travel from one part of the body to a distant site where they should not be. This is called metastasis…”

- “One of the biggest obstacles to a “cure” is the fact that cancer is not one single, simple, straightforward disease, but a condition with mind-boggling complexity.”

- “In fact, there didn’t seem to be any individual genes that “caused” cancer at all; instead, it seemed to be random somatic mutations that combined to cause cancers.”

- “Breast cancer kills only when it becomes metastatic. Prostate cancer kills only when it becomes metastatic. You could live without either of those organs.”

- “Five decades into the war on cancer, it seems clear that no single “cure” is likely to be forthcoming. Rather, our best hope likely lies in figuring out better ways to attack cancer on all three of these fronts: prevention, more targeted and effective treatments, and comprehensive and accurate early detection.”

Prevention

Of all the Horsemen, cancer is probably the hardest to prevent. It is probably also the one where bad luck in various forms plays the greatest role, such as in the form of accumulated somatic mutations. The only modifiable risks that really stand out in the data are smoking, insulin resistance, and obesity (all to be avoided)—and maybe pollution (air, water, etc.), but the data here are less clear.

Peter Attia – Outlive

- “And extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 40) is associated with a 52 percent greater risk of death from all cancers in men, and 62 percent in women.”

- “I suspect that the association between obesity, diabetes, and cancer is primarily driven by inflammation and growth factors such as insulin.”

- “Thus, insulin acts as a kind of cancer enabler, accelerating its growth. Source: NCI (2022a). This in turn suggests that metabolic therapies, including dietary manipulations that lower insulin levels, could potentially help slow the growth of some cancers and reduce cancer risk.”

- “I’m not suggesting that it’s possible to “starve” cancer or that any particular diet will magically make cancer go away; cancer cells always seem to be able to obtain the energy supply they need. What I am saying is that we don’t want to be anywhere on that spectrum of insulin resistance to type 2 diabetes, where our cancer risk is clearly elevated. To me, this is the low-hanging fruit of cancer prevention, right up there with quitting smoking.“

I would go so far as to argue that early detection is our best hope for radically reducing cancer mortality.

Peter Attia – Outlive

Detection

- “Out of dozens of different types of cancers, we have agreed-upon, reliable screening methods for only five: lung (for smokers), breast, prostate, colorectal, and cervical. Even so, mainstream guidelines have been waving people away from some types of early screening, such as mammography in women and blood testing for PSA, prostate-specific antigen, in men. In part this has to do with cost, and in part this has to do with the risk of false positives that may lead to unnecessary or even dangerous treatment (entailing further costs).”

Liquid Biopsies

- “I am also cautiously optimistic about pairing these tried-and-true staples of cancer screening with emerging methods, such as “liquid biopsies,” which can detect trace amounts of cancer-cell DNA via a simple blood test.”

- “Using very-high-throughput screening and a massive AI engine, the Galleri test can glean two crucial pieces of information from this sample of blood: Is cancer present? And if so, where is it? From what part of the body did it most likely originate?”

- “In this study, the Galleri test proved to have a very high specificity, about 99.5 percent, meaning only 0.5 percent of tests yielded a false positive. If the test says you have cancer, somewhere in your body, then it is likely that you do. The trade-off is that the resulting sensitivity can be low, depending on the stage. (That is, even if the test says you don’t have cancer, you are not necessarily in the clear.)”

Think asymmetric risk: It’s possible that not screening early and frequently enough is the most dangerous option.

Peter Attia – Outlive

False Positives

- “In fact, in this low-risk group, the “positive predictive value” of mammography is only about 10 percent—meaning that if you do test positive, there is only about a one-in-ten chance that you actually have breast cancer. In other populations, with greater overall prevalence (and risk), the test performs much better.”

- “We need to think in terms of stacking test modalities—incorporating ultrasound and MRI in addition to mammography, for example, when looking for breast cancer. With multiple tests, our resolution improves and fewer unnecessary procedures will be performed.”

- “Despite all this, even something as advanced as the best DWI MRI is not without problems, if used in isolation. While the sensitivity of this test is very high (meaning it’s very good at finding cancer if cancer is there, hence very few false negatives), the specificity is relatively low (which means it’s not as good at telling you when you don’t have cancer, hence a lot of false positives). … The more you increase one, the more you decrease the other.”

The key question we want to answer is, Will our patient die with prostate cancer, as many men do, or will he die from it?

Peter Attia – Outlive

Colonoscopy

- “The purpose of the colonoscopy is to look not only for full-fledged tumors but also for polyps, which are growths that form in the lining of the colon. … Not all polyps become cancer, but all colon cancers came from polyps.”

- “In my practice, we go further, typically encouraging average-risk individuals to get a colonoscopy by age forty—and even sooner if anything in their history suggests they may be at higher risk.”

- “Two or three years might seem like a very short window of time to repeat such an involved procedure, but colon cancer has been documented to appear within the span of as little as six months to two years after a normal colonoscopy.”

Warbug Effect

- “In the 1920s, a German physiologist named Otto Warburg discovered that cancer cells had a strangely gluttonous appetite for glucose, devouring it at up to forty times the rate of healthy tissues.”

- “This phenomenon was dubbed the Warburg effect, and even today, one way to locate potential tumors is by injecting the patient with radioactively labeled glucose and then doing a PET scan to see where most of the glucose is migrating. Areas with abnormally high glucose concentrations indicate the possible presence of a tumor.”

- “The Warburg effect, also known as anaerobic glycolysis, turns the same amount of glucose into a little bit of energy and a whole lot of chemical building blocks—which are then used to build new cells rapidly. Thus, the Warburg effect is how cancer cells fuel their own proliferation. But it also represents a potential vulnerability in cancer’s armor.”

Treatment

- “Combining surgery and radiation therapy is pretty effective against most local, solid-tumor cancers. But while we’ve gotten fairly good at this approach, we have essentially maxed out our ability to treat cancers this way.”

- “And surgery is of limited value when cancer has metastasized, or spread. Metastatic cancers can be slowed by chemotherapy, but they virtually always come back, often more resistant to treatment than ever.”

- “Meanwhile, as cancer researcher Robert Gatenby points out, those cancer cells that do manage to survive chemotherapy often end up acquiring mutations that make them stronger, like cockroaches that develop resistance to insecticides.”

- “Contrary to popular belief, killing cancer cells is actually pretty easy.”

- “The game is won by killing cancers while sparing the normal cells. Selective killing is the key.”

- “Ultimately, successful treatments will need to be both systemic and specific to a particular cancer type.”

Immunotherapy

- “I feel that immunotherapy, in particular, has enormous promise.”

- “As of yet, the various immunotherapy treatments that have been approved still benefit only a fairly small percentage of patients. About a third of cancers can be treated with immunotherapy, and of those patients, just one-quarter will actually benefit (i.e., survive). That means that only 8 percent of potential cancer deaths could be prevented by immunotherapy, according to an analysis by oncologists Nathan Gay and Vinay Prasad.”

- “But when patients do respond to immunotherapy, and go into complete remission, they often stay in remission. Between 80 and 90 percent of so-called complete responders to immunotherapy remain disease-free fifteen years out.”

- “It took many more years and several iterations, but Rosenberg and his team adapted a technique that had been developed in Israel that involved taking T cells from a patient’s blood, then using genetic engineering to add antigen receptors that were specifically targeted to the patient’s tumors. Now the T cells were programmed to attack the patient’s cancer. Known as chimeric antigen receptor T cells (or CAR-T), these modified T cells could be multiplied in the lab and then infused back into the patient.”

- “Instead of activating T cells to go kill the cancer, the checkpoint inhibitors help make the cancer visible to the immune system.”

- “One very promising technique is called adoptive cell therapy (or adoptive cell transfer, ACT). ACT is a class of immunotherapy whereby supplemental T cells are transferred into a patient, like adding reinforcements to an army, to bolster their ability to fight their own tumor. These T cells have been genetically programmed with antigens specifically targeted at the patient’s individual tumor type.”

- “ACT effectively means designing a new, customized anticancer drug for each individual patient. This is obviously a costly proposition, and a very labor-intensive process, but it has a lot of promise. The proof of principle is here, but much more work is needed, not only to improve the efficacy of this approach but also to enable us to deliver this treatment more widely and more easily.”

Dietary Intervention

- “The results are important because they show not only that a cancer cell’s metabolism is a valid target for therapy but that a patient’s metabolic state can affect the efficacy of a drug. In this case, the animals’ ketogenic diet seemed to synergize with what was otherwise a somewhat disappointing treatment, and together they proved to be far more powerful than either one alone.”

- “Work by Valter Longo of the University of Southern California and others has found that fasting, or a fasting-like diet, increases the ability of normal cells to resist chemotherapy, while rendering cancer cells more vulnerable to the treatment.””A randomized trial in 131 cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy found that those who were placed on a “fasting-mimicking diet” (basically, a very low-calorie diet designed to provide essential nutrients while reducing feelings of hunger) were more likely to respond to chemotherapy and to feel better physically and emotionally.”

- “As Keith Flaherty, a medical oncologist and the director of developmental therapeutics at Massachusetts General Hospital, explained to me, the best strategy to target cancer is likely by targeting multiple vulnerabilities of the disease at one time, or in sequence. By stacking different therapies, such as combining a PI3K inhibitor with a ketogenic diet, we can attack cancer on multiple fronts, while also minimizing the likelihood of the cancer developing resistance (via mutations) to any single treatment.”

Chapter 9 – Chasing Memory

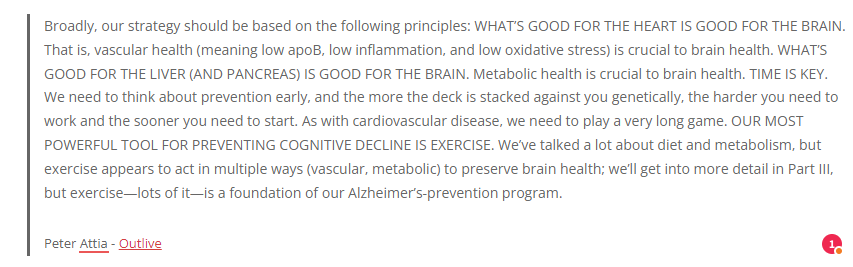

Broadly, our strategy should be based on the following principles: WHAT’S GOOD FOR THE HEART IS GOOD FOR THE BRAIN. That is, vascular health (meaning low apoB, low inflammation, and low oxidative stress) is crucial to brain health. WHAT’S GOOD FOR THE LIVER (AND PANCREAS) IS GOOD FOR THE BRAIN. Metabolic health is crucial to brain health. TIME IS KEY. We need to think about prevention early, and the more the deck is stacked against you genetically, the harder you need to work and the sooner you need to start. As with cardiovascular disease, we need to play a very long game. OUR MOST POWERFUL TOOL FOR PREVENTING COGNITIVE DECLINE IS EXERCISE. We’ve talked a lot about diet and metabolism, but exercise appears to act in multiple ways (vascular, metabolic) to preserve brain health; we’ll get into more detail in Part III, but exercise—lots of it—is a foundation of our Alzheimer’s-prevention program.

Peter Attia – Outlive

Alzheimer’s Disease

- “Alzheimer’s disease is perhaps the most difficult, most intractable of the Horsemen diseases.”

- “It appears, then, that the presence of amyloid-beta plaques may be neither necessary for the development of Alzheimer’s disease nor sufficient to cause it.”

- “While female Alzheimer’s patients outnumber men by two to one, the reverse holds true for Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s, both of which are twice as prevalent in men.”

Risk Factors

- “One important section of the cognitive testing evaluates the patient’s sense of smell. Can they correctly identify scents such as coffee, for example? Olfactory neurons are among the first to be affected by Alzheimer’s disease.”

- “Having type 2 diabetes doubles or triples your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, about the same as having one copy of the APOE e4 gene.”

- “Insulin seems to play a key role in memory function. Insulin receptors are highly concentrated in the hippocampus, the memory center of the brain. Several studies have found that spraying insulin right into subjects’ noses—administering it as directly as possible into their brains—quickly improves cognitive performance and memory, even in people who have already been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.”

- “Another somewhat surprising risk factor that has emerged is hearing loss. Studies have found that hearing loss is clearly associated with Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s not a direct symptom. Rather, it seems hearing loss may be causally linked to cognitive decline, because folks with hearing loss tend to pull back and withdraw from interactions with others. When the brain is deprived of inputs—in this case auditory inputs—it withers.”

Prevention & Treatment

- “Sleep is also a very powerful tool against Alzheimer’s disease, as we’ll see in chapter 16.”

- “Another surprising intervention that may help reduce systemic inflammation, and possibly Alzheimer’s disease risk, is brushing and flossing one’s teeth.”

- “The best interpretation I can draw from the literature suggests that at least four sessions per week, of at least twenty minutes per session, at 179 degrees Fahrenheit (82 degrees Celsius) or hotter seems to be the sweet spot to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s by about 65 percent (and the risk of ASCVD by 50 percent).”

Exercise Intervention

- “The single most powerful item in our preventive tool kit is exercise, which has a two-pronged impact on Alzheimer’s disease risk: it helps maintain glucose homeostasis, and it improves the health of our vasculature.”

- “Evidence also demonstrates a linear relationship between cognitive decline and increased intimal media thickness in the carotid artery, a major blood vessel that feeds the brain.”

- “The more of these networks and subnetworks that we have built up over our lifetime, via education or experience, or by developing complex skills such as speaking a foreign language or playing a musical instrument, the more resistant to cognitive decline we will tend to be. The brain can continue functioning more or less normally, even as some of these networks begin to fail. This is called “cognitive reserve,” and it has been shown to help some patients to resist the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.”

- “There is a parallel concept known as “movement reserve” that becomes relevant with Parkinson’s disease. People with better movement patterns, and a longer history of moving their bodies, such as trained or frequent athletes, tend to resist or slow the progression of the disease as compared to sedentary people.”

- “Exercise is the only intervention shown to delay the progression of Parkinson’s.”

- “The evidence suggests that tasks or activities that present more varied challenges, requiring more nimble thinking and processing, are more productive at building and maintaining cognitive reserve. Simply doing a crossword puzzle every day, on the other hand, seems only to make people better at doing crossword puzzles. The same goes for movement reserve: dancing appears to be more effective than walking at delaying symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, possibly because it involves more complex movement.”

- “Strength training is likely just as important. A study looking at nearly half a million patients in the United Kingdom found that grip strength, an excellent proxy for overall strength, was strongly and inversely associated with the incidence of dementia (see figure 8).”

Dietary Intervention

- “Because metabolism plays such an outsize role with at-risk e4 patients like Stephanie, our first step is to address any metabolic issues they may have. Our goal is to improve glucose metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress. One possible recommendation for someone like her would be to switch to a Mediterranean-style diet, relying on more monounsaturated fats and fewer refined carbohydrates, in addition to regular consumption of fatty fish.”

- “Studies in Alzheimer’s patients find that while their brains become less able to utilize glucose, their ability to metabolize ketones does not decline.”

- “A systematic review of randomized controlled trials found that ketogenic therapies improved general cognition and memory in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.”

Part III

Chapter 10 – Thinking Tactically

“In Medicine 3.0, we have five tactical domains that we can address in order to alter someone’s health.

- The first is exercise, which I consider to be by far the most potent domain in terms of its impact on both lifespan and healthspan.

- Next is diet or nutrition—or as I prefer to call it, nutritional biochemistry.

- The third domain is sleep, which has gone underappreciated by Medicine 2.0 until relatively recently.

- The fourth domain encompasses a set of tools and techniques to manage and improve emotional health.

- Our fifth and final domain consists of the various drugs, supplements, and hormones that doctors learn about in medical school and beyond. I lump these into one bucket called exogenous molecules, meaning molecules we ingest that come from outside the body.”

When I evaluate new patients, I’m always asking three key questions:

- Are they overnourished or undernourished? That is, are they taking in too many or too few calories?

- Are they undermuscled or adequately muscled?

- Are they metabolically healthy or not?

Chapter 11 – Exercise

So if you adopt only one new set of habits based on reading this book, it must be in the realm of exercise.

Peter Attia – Outlive

Benefits

- “The data demonstrating the effectiveness of exercise on lifespan are as close to irrefutable as one can find in all human biology. Yet if anything, I think exercise is even more effective at preserving healthspan than extending lifespan. There is less hard evidence here, but I believe that this is where exercise really works its magic when applied correctly. I tell my patients that even if exercise shortened your life by a year (which it clearly does not), it would still be worthwhile purely for the healthspan benefits, especially in middle age and beyond.”

- “But at least five factors[*3] increase my confidence in at least the partial causality of this relationship. First, the magnitude of the effect size is very large. Second, the data are consistent and reproducible across many studies of disparate populations. Third, there is a dose-dependent response (the fitter you are, the longer you live). Fourth, there is great biologic plausibility to this effect, via the known mechanisms of action of exercise on lifespan and healthspan. And fifth, virtually all experimental data on exercise in humans suggest that it supports improved health.”

- “Exercise is by far the most potent longevity “drug.” No other intervention does nearly as much to prolong our lifespan and preserve our cognitive and physical function. But most people don’t do nearly enough—and exercising the wrong way can do as much harm as good.”

- “I used to prioritize nutrition over everything else, but I now consider exercise to be the most potent longevity “drug” in our arsenal, in terms of lifespan and healthspan. The data are unambiguous: exercise not only delays actual death but also prevents both cognitive and physical decline, better than any other intervention.”

- “There are reams of data supporting the notion that even a fairly minimal amount of exercise can lengthen your life by several years.”

- “Going from zero weekly exercise to just ninety minutes per week can reduce your risk of dying from all causes by 14 percent.”

VO2 Max

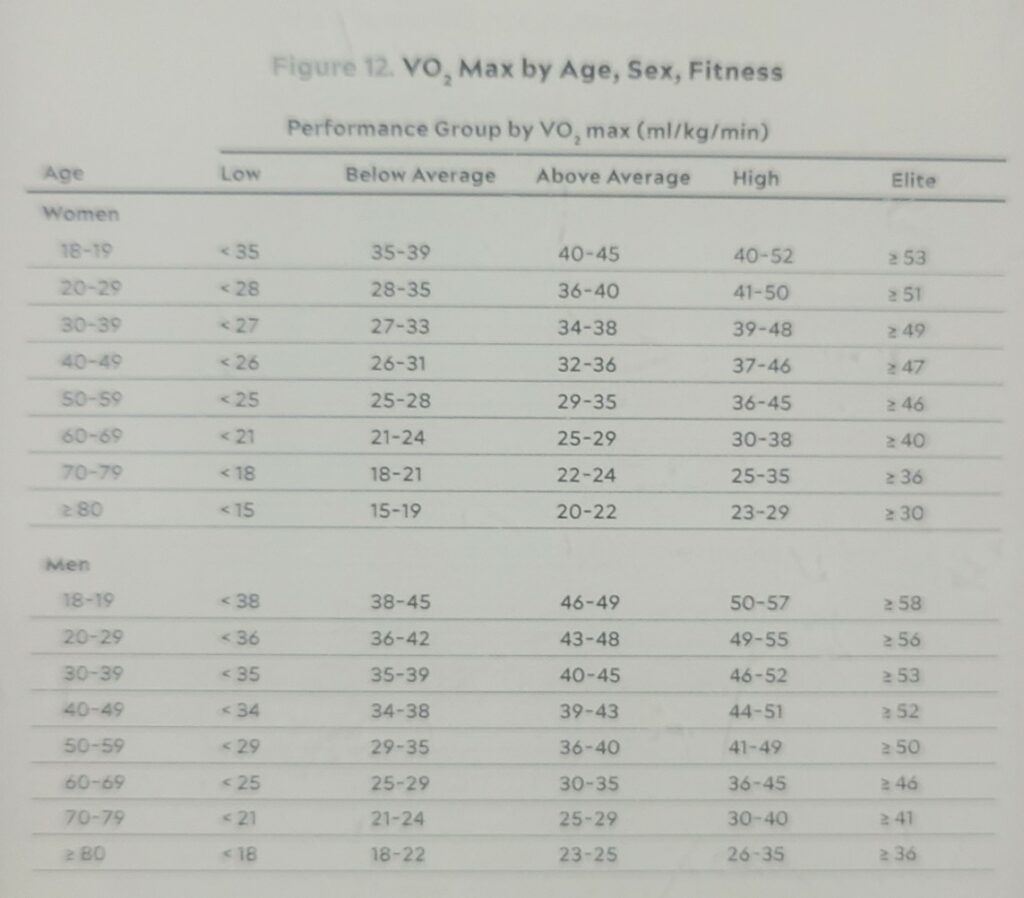

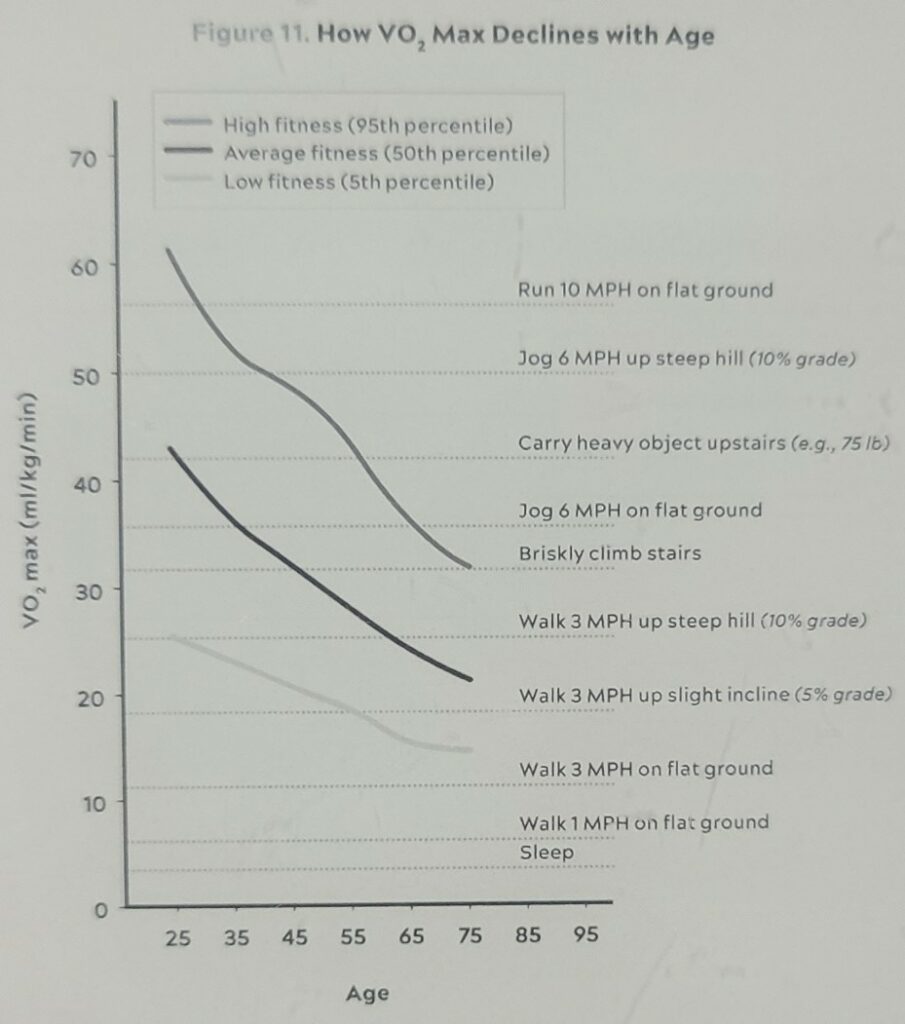

- “It turns out that peak aerobic cardiorespiratory fitness, measured in terms of VO2 max, is perhaps the single most powerful marker for longevity. VO2 max represents the maximum rate at which a person can utilize oxygen. This is measured, naturally, while a person is exercising at essentially their upper limit of effort.”

- “VO2 max is typically expressed in terms of the volume of oxygen a person can use, per kilogram of body weight, per minute. An average forty-five-year-old man will have a VO2 max around 40 ml/kg/min, while an elite endurance athlete will likely score in the high 60s and above. An unfit person in their thirties or forties, on the other hand, might score only in the high 20s on a VO2 max test, according to Mike Joyner, an exercise physiologist and researcher at the Mayo Clinic.”

- “A person who smokes has a 40 percent greater risk of all-cause mortality (that is, risk of dying at any moment) than someone who does not smoke, representing a hazard ratio or (HR) of 1.40. This study found that someone of below-average VO2 max for their age and sex (that is, between the 25th and 50th percentiles) is at double the risk of all-cause mortality compared to someone in the top quartile (75th to 97.6th percentiles). Thus, poor cardiorespiratory fitness carries a greater relative risk of death than smoking.“

Muscle Mass & Strength

- “A ten-year observational study of roughly 4,500 subjects ages fifty and older found that those with low muscle mass were at 40 to 50 percent greater risk of mortality than controls, over the study period. Further analysis revealed that it’s not the mere muscle mass that matters but the strength of those muscles, their ability to generate force.”

- “As figure 10 reveals, falls are by far the leading cause of accidental deaths in those ages sixty-five and older—and this is without even counting the people who die three or six or twelve months after their nonfatal but still serious fall pushed them into a long and painful decline.”

Centenarian Decathlon

Think of the Centenarian Decathlon as the ten most important physical tasks you will want to be able to do for the rest of your life.

- Hike 1.5 miles on a hilly trail.

- Get up off the floor under your own power, using a maximum of one arm for support.

- Pick up a young child from the floor.

- Carry two five-pound bags of groceries for five blocks.

- Lift a twenty-pound suitcase into the overhead compartment of a plane.

- Balance on one leg for thirty seconds, eyes open. (Bonus points: eyes closed, fifteen seconds.)

- Have sex.

- Climb four flights of stairs in three minutes.

- Open a jar.

- Do thirty consecutive jump-rope skips.

- “The record for the hundred-meter dash for women ages one hundred and up is about forty-one seconds.” LOL

- “Over the next thirty or forty years, your muscle strength will decline by about 8 to 17 percent per decade—accelerating as time goes on. So if you want to pick up that thirty-pound grandkid or great-grandkid when you’re eighty, you’re going to have to be able to lift about fifty to fifty-five pounds now. Without hurting yourself. Can you do that?”

- Determine your current decathlon challenge to be on pace for your centenarian decathlon (APP).

- “Together, we come up with a list of ten or fifteen events in their personal Centenarian Decathlon, representing their goals for their later decades. This then determines how they should be training.”

- “The beauty of the Centenarian Decathlon is that it is broad yet unique to each individual. Nor is it limited to ten events; for most people it ends up being more, depending on their goals.”

- “When my patients say they are more interested in being kick-ass fifty-year-olds than Centenarian Decathletes, I reply that there is no better way to make that happen than to set a trajectory toward being vibrant at one hundred (or ninety, or eighty) just as an archer who trains at 100 yards will be more accurate at 50.”

- “As Centenarian Decathletes, we are no longer training for a specific event, but to become a different sort of athlete altogether: an athlete of life.”

Chapter 12 – Training 101

The three dimensions in which we want to optimize our fitness are aerobic endurance and efficiency (aka cardio), strength, and stability.

PETER ATTIA – OUTLIVE

Aerobic Endurance & Efficiency (Cardio)

- “The various levels of intensity all count as cardio but are fueled by multiple different energy systems. For our purposes, we are interested in two particular regions of this continuum: long, steady endurance work, such as jogging or cycling or swimming, where we are training in what physiologists call zone 2, and maximal aerobic efforts, where VO2 max comes into play.”

Zone 2

- “Zone 2 is more or less the same in all training models: going at a speed slow enough that one can still maintain a conversation but fast enough that the conversation might be a little strained.”

- “If you know your maximum heart rate—not estimated, but your actual maximum, the highest number you’ve ever seen on a heart rate monitor—your zone 2 will correspond to between approximately 70 and 85 percent of that peak number, depending on your fitness levels. That’s a big range, so when starting people out, I prefer they rely on their rate of perceived exertion, or RPE, also known as the “talk test.””

- “Typically, someone working at a lower relative intensity will be burning more fat, while at higher intensities they would rely more on glucose. The healthier and more efficient your mitochondria, the greater your ability to utilize fat, which is by far the body’s most efficient and abundant fuel source. This ability to use both fuels, fat and glucose, is called “metabolic flexibility,” and it is what we want.”

- “They had each group ride a stationary bicycle at a given level of intensity relative to their fitness (about 80 percent of their maximum heart rate), while the scientists analyzed the amount of oxygen they consumed and the CO2 they exhaled in order to determine how efficiently they produced power—and what primary fuels they were using. The differences they found were striking. The professional cyclists could zoom along, producing a huge amount of power while still burning primarily fat. But the subjects with metabolic syndrome relied almost entirely on glucose for their fuel source, even from the first pedal stroke. They had virtually zero ability to tap into their fat stores, meaning they were metabolically inflexible: able to use only glucose but not fat.”

- “A professional cyclist might spend thirty to thirty-five hours a week training on his or her bike, and 80 percent of that time in zone 2.”

- “(The catch is that a professional rider’s zone 2 output feels like zone 5 for most people.)”

- “In technical terms, San Millán describes zone 2 as the maximum level of effort that we can maintain without accumulating lactate.”

- “Because I am a numbers guy and I love biomarkers and feedback, I often test my own lactate while I am working out this way, using a small handheld lactate monitor, to make sure my pacing is correct. The goal is to keep lactate levels constant, ideally between 1.7 and 2.0 millimoles.”

- “Mitochondria are incredibly plastic, and when we do aerobic exercise, it stimulates the creation of many new and more efficient mitochondria through a process called mitochondrial biogenesis, while eliminating ones that have become dysfunctional via a recycling process called mitophagy (which is like autophagy, touched on in chapter 5, but for mitochondria). A person who exercises frequently in zone 2 is improving their mitochondria with every run, swim, or bike ride. But if you don’t use them, you lose them.”

- “Chronic blood glucose elevations damage organs from our heart to our brain to our kidneys and nearly everything in between—even contributing to erectile dysfunction in men.”

- “This in turn explains why exercise, especially in zone 2, can be so effective in managing both type 1 and type 2 diabetes: It enables the body to essentially bypass insulin resistance in the muscles to draw down blood glucose levels. I have one patient with type 1 diabetes, meaning he produces zero insulin, who keeps his glucose in check almost entirely by walking briskly for six to ten miles every day, and sometimes more.”

- “The key is to find an activity that fits into your lifestyle, that you enjoy doing, and that enables you to work at a steady pace that meets the zone 2 test: You’re able to talk in full sentences, but just barely.”

- “Based on multiple discussions with San Millán and other exercise physiologists, it seems that about three hours per week of zone 2, or four 45-minute sessions, is the minimum required for most people to derive a benefit and make improvements, once you get over the initial hump of trying it for the first time.”

- “One way to track your progression in zone 2 is to measure your output in watts at this level of intensity. … You take your average wattage output for a zone 2 session and divide it by your weight to get your watts per kilogram, which is the number we care about. So if you weigh 60 kilos (about 132 pounds) and can generate 125 watts in zone 2, that works out to a bit more than 2 watts/kg, which is about what one would expect from a reasonably fit person.”

- “Zone 2 can be a bit boring on its own, so I typically use the time to listen to podcasts or audiobooks, or just think about issues that I’m working on”

VO2 Max

- “Typically, for patients who are new to exercising, we introduce VO2 max training after about five or six months of steady zone 2 work.”

- “Testing is widely available, even from some of the larger fitness chains. The bad news is that the VO2 max test is an unpleasant affair that entails riding an exercise bike or running on a treadmill at ever greater intensity, while wearing a mask designed to measure oxygen consumption and CO2 production. The peak amount of oxygen you consume, typically close to the point at which you “fail,” meaning the point where you just can’t keep going, yields your VO2 max. We have all our patients do the test at least annually, and they almost all hate it. We then compare their results, normalized by weight, to the population of their age and sex.”

- “Ideally, I want them to target the “elite” range for their age and sex (roughly the top 2 percent). If they achieve that level, I say good job—now let’s reach for the elite level for your sex, but two decades younger.”

- “Studies suggest that your VO2 max will decline by roughly 10 percent per decade—and up to 15 percent per decade after the age of fifty.”

- “Improving your VO2 max from the very bottom quartile to the quartile above (i.e., below average) is associated with almost a 50 percent reduction in all-cause mortality, as we saw earlier.”

- “One study found that boosting elderly subjects’ VO2 max by 6 ml/kg/min, or about 25 percent, was equivalent to subtracting twelve years from their age.”

- “The beauty of this is that VO2 max can always be improved by training, no matter how old you are. Don’t believe me? Then let me introduce you to an amazing Frenchman named Robert Marchand, who set an age-group world record in 2012 by cycling 24.25 kilometers in an hour, at the age of 101. Apparently, he wasn’t satisfied with that performance, so he decided he needed to train harder. Following a strict program designed by top coaches and physiologists, he managed to boost his VO2 max from an already-impressive 31 ml/kg/min up to 35 ml/kg/min, which would put him in the elite 2.5 percent of men in their eighties. Two years later, now 103, he came back and broke his own record, riding almost twenty-seven kilometers in an hour.”

- “Where HIIT intervals are very short, typically measured in seconds, VO2 max intervals are a bit longer, ranging from three to eight minutes—and a notch less intense.”

- “The tried-and-true formula for these intervals is to go four minutes at the maximum pace you can sustain for this amount of time—not an all-out sprint, but still a very hard effort. Then ride or jog four minutes easy, which should be enough time for your heart rate to come back down to below about one hundred beats per minute. Repeat this four to six times and cool down.”

- “A single workout per week in this zone will generally suffice. You’ll pretty quickly find that it boosts your performance across the rest of your exercise program as well—and, more importantly, in the rest of your life.”

Strength

I think of strength training as a form of retirement saving. Just as we want to retire with enough money saved up to sustain us for the rest of our lives, we want to reach older age with enough of a “reserve” of muscle (and bone density) to protect us from injury and allow us to continue to pursue the activities that we enjoy.

PETER ATTIA – OUTLIVE

- “But muscle mass may be the least important metric here. According to Andy Galpin, a professor of kinesiology at California State University, Fullerton, and one of the foremost authorities on strength and performance, we lose muscle strength about two to three times more quickly than we lose muscle mass. And we lose power (strength x speed) two to three times faster than we lose strength.”

- Sarcopenia is a prime marker for a broader clinical condition called frailty, where a person meets three of these five criteria:

- unintended weight loss

- exhaustion or low energy

- low physical activity

- slowness in walking

- weak grip strength (about which more soon).

- “One study looked at sixty-two frail seniors (average age seventy-eight) who engaged in a program of strength training and found that even after six months of pure strength training, half of the subjects did not gain any muscle mass. They also didn’t lose any muscle mass, likely thanks to the weight training, but the upshot is, it is very difficult to put on muscle mass later in life.”